A Movement in a Moment: The Düsseldorf School

Find out how a husband and wife’s photos of industrial buildings changed photography forever

Visitors to Photo London, the British capital’s highly successful photo fair which takes place this week, may find it hard to imagine a time when the European art world did not prize photographic works.

However, as Martin Parr explains in The Photobook: A History Volume I, “during the 1970s the focus of attention in photography shifted away from Europe to the United States. The primary reason for this was the fact that since the early 1960s the formidable weight of American art institutions – museums, universities, the New York art market – began to support photography in the same kind of way that it had supported Abstract Expressionism.”

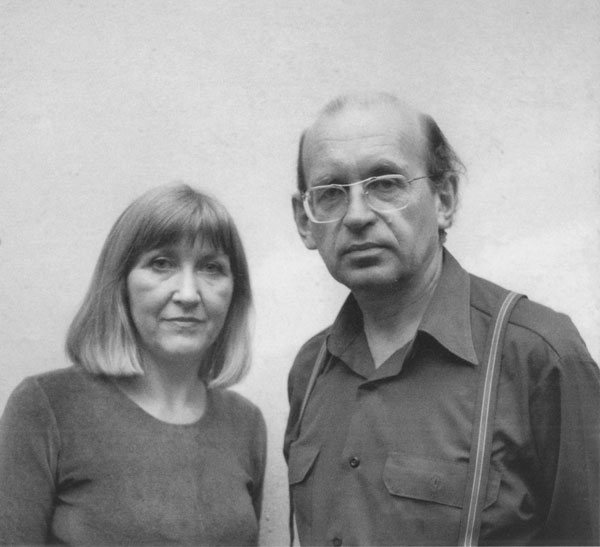

Yet, in the relatively parochial European city of Düsseldorf, photography was being put to strange new uses. “In 1970 a book called Anonyme Skulpturen (Anonymous Sculptures) was published to some acclaim in the avant-garde art world, though to rather less cheer in the photographic world,” explains Parr and his fellow author Gerry Badger. “The photographers were the German husband-and-wife team Bernd and Hilla Becher, and the work – flat, undemonstrative, elevational photographs of industrial architecture and machinery – looked both backwards and forwards.”

Backwards because the Bechers shots of slightly outdated blast furnaces and water towers reached back to a categorical, typological style of photography popular during the early 20th century; yet forward looking because of the way in which the Bechers’ pictures integrated photography into contemporary art practices, giving rise to an entire photographic movement, known today as The Düsseldorf School. Known for their rigorous devotion to the 1920s German tradition of Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity), the Bechers’ photographs were clear, black and white pictures of industrial archetypes.

“The Bechers influenced a generation of talented photographers at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf in Germany, introducing a cool, objective, documentary approach to art photography,” explain the editors of our art history title, Art In Time. “The Düsseldorf School references not only a group of artists and an institutional affiliation, but also a shared aesthetic – a commitment to controlled objectivity and a documentary orientation.

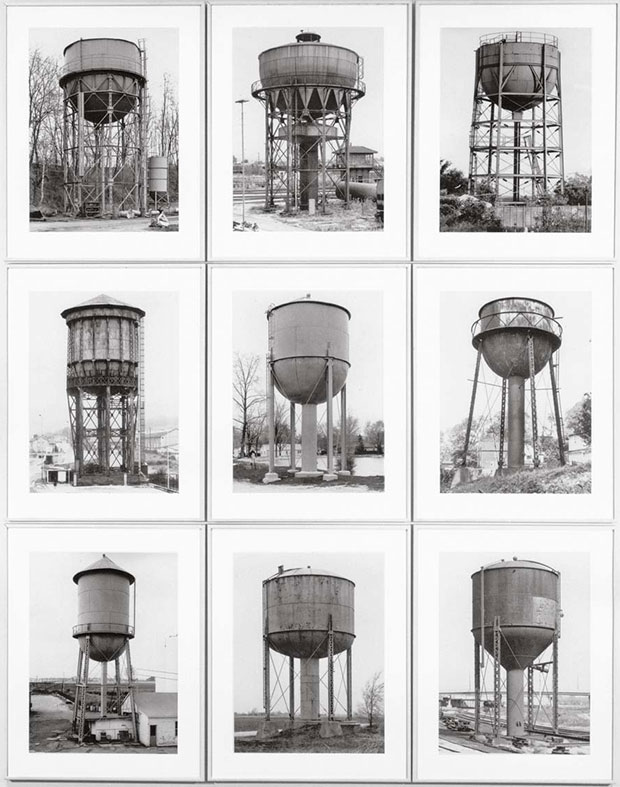

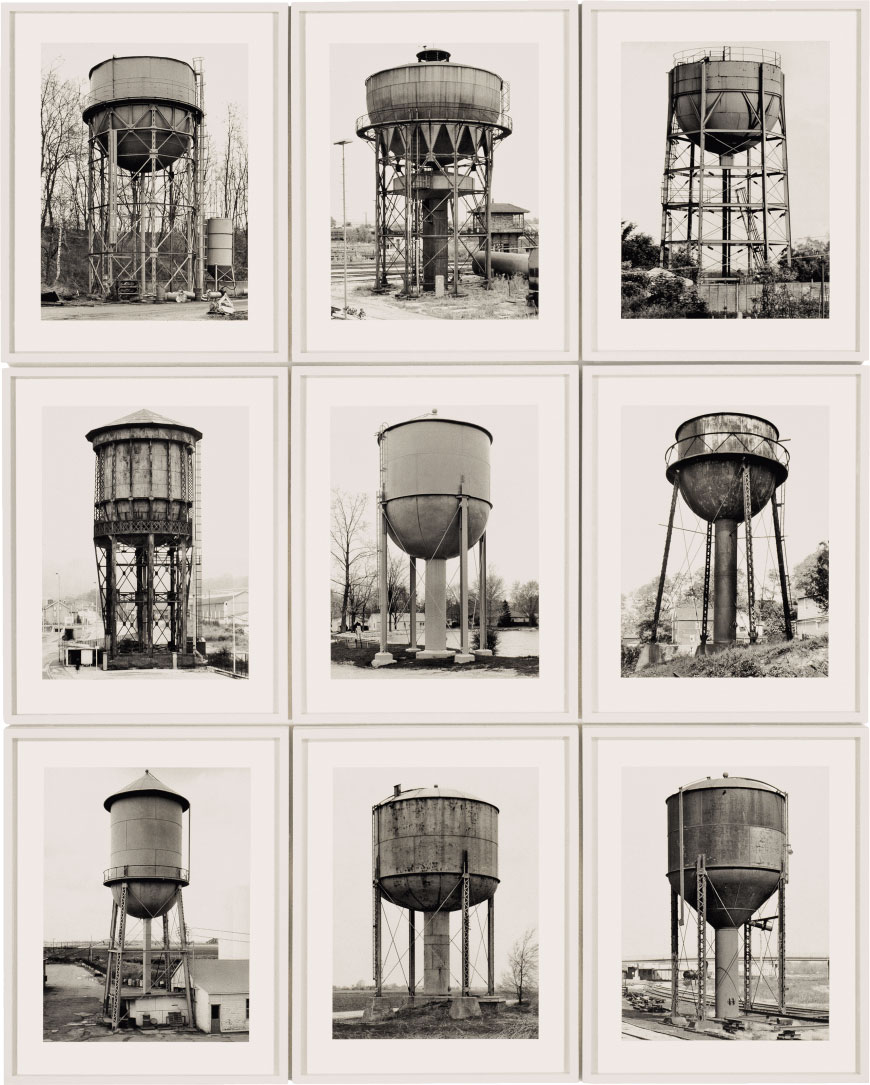

“The Bechers specialized in the photography of anonymous industrial sites and structures, methodically employing the same neutral perspective in each image, as in Water Towers. The nine nineteenth-century metal water towers are displayed in a grid as a single work, the black-and-white images revealing the differences between objects that had an identical function, and so bestowing an aesthetic value on them.

“The legacy of the early-twentieth century photographer August Sander, who aimed to photograph all types of German people, is palpable in the Becher strategy: systemic, objective and comprehensive. The Bechers’ work also resonates with that of the nineteenth-century photographer Édouard Baldus, who documented French national monuments, and the twentieth-century grid presentation of Minimalist artists, for example, Carl Andre. With strong traditions buttressing their work, the Bechers significantly repositioned photography within the art world hierarchy. They were part of a larger discourse seeking found sculpture in the landscape, and the display of their work at large scales initiated a tendency among some of their students to create very large prints, often digitally manipulated, that command the museum wall and refuse to accept a second-place position vis-à-vis paintings.”

By the 1990s, this practice of printing a cool, impersonal image in billboard dimensions had become a bit of an art-world cliché. However, this in no way undermines the achievements of the Bechers and their followers.

“The Düsseldorf School aesthetic speaks to the post-industrial depersonalized experience. Printing techniques have been appropriated from advertising; images may be secured to Plexiglas sheets. Students of the Bechers during the 1970s included Andreas Gursky, Candida Höfer, Axel Hütte, Thomas Ruff and Thomas Struth, all of whom went on to become well known photographers in their own rights.

Andreas Gursky, Candida Höfer, Axel Hütte, Thomas Ruff and Thomas Struth went on to modify the approach of their teachers, the Bechers, by applying new technical possibilities and a personal and contemporary vision, while retaining the documentary method their tutors propounded.

“Thomas Struth’s Musée du Louvre 4, Paris is part of Struth’s museum series, in which he photographed people looking at art, for example Géricault’s famous Romantic masterpiece The Raft of the Medusa, representing the starving survivors of a shipwreck sighting a rescue ship. Each observer is implicated in the viewing.”

In this way, these simple tourists are given, as Mark Durden puts it in our book Photography Today, but also the photographer is making a claim "about his own artistic heritage."

By entering into this kind of fine-art dialogue, the Bechers, Struth and co have in turn helped raise photography's position within the visual arts.

Anyone wanting to see works from this school at Photo London should take a look at Thomas Struth at the Mack stand; Candida Höfer at Galerie Thomas Zander and at Ben Brown Fine Art; and Axel Hütte’s photographs on display at Strange and Familiar: Britain as Revealed by International Photographers, across town at the Barbican.

Meanwhile, for more on the Dusseldorf School’s place within the greater sweep of art history get Art In Time and for more on the photo book’s place in photographic history consider our three-volume edition, The Photobook: A History by Martin Parr and Gerry Badger.