New York loves Mike Kelley

The late artist's huge retrospective at MoMA PS1 receives glowing write-ups

Mike Kelley might have drawn from the most populist sources throughout his career, yet the New York arts establishment has met his PS1 retrospective, which opened yesterday and runs until 2 February 2014, with high-minded praise.

“It will be the first time the entire building has been given over to one artist,” explained Randy Kennedy in The New York Times, “with a survey that covers almost three decades of video, sculpture, performance, painting and installation, and seeks to make a case for Kelley’s career, even cut short, as one of the most important and influential in contemporary art.”

Kennedy's isn't alone among the press previews in noting how apt a setting PS1 is. The Victorian building originally served as a school, and “again and again in his career, Kelley — whose father was a public school janitorial chief in Detroit — returned to the school as the crucible of American identity, of values, of high and low culture, of repression and cruelty and of modern folk rituals.”

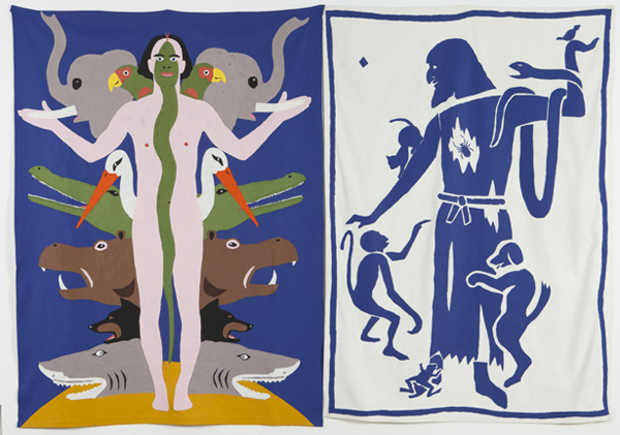

The Wall Street Journal gets a good handle on just what kind of low culture Kelley picked up on; not the bright Brillo boxes and road signs of the early Pop artists, but the seedier, more shop-worn material that came later.

“Mr. Kelley grew up in a middle-class suburb of Detroit,” wrote the WSJ's Kelly Crow, “where he watched the art establishment chase after Andy Warhol's slick appropriation of soup cans and Hollywood starlets. He, however, felt more drawn to lower-end pop culture artefacts like cheeky comics, frat-party fliers and soiled stuffed animals. By focusing on the overlooked ephemera of America's basements, he influenced generations of thrift-store artists who followed.”

Justin Jones, writing in the Daily Beast, was overawed by the sheer number of exhibits displayed. Kelley, who committed suicide in 2012, was an incredibly prodigious artist, “and had a tremendously impactful thirty-five year career producing genre-defying works in every medium: from massive stuffed-animal sculptures to installations.”

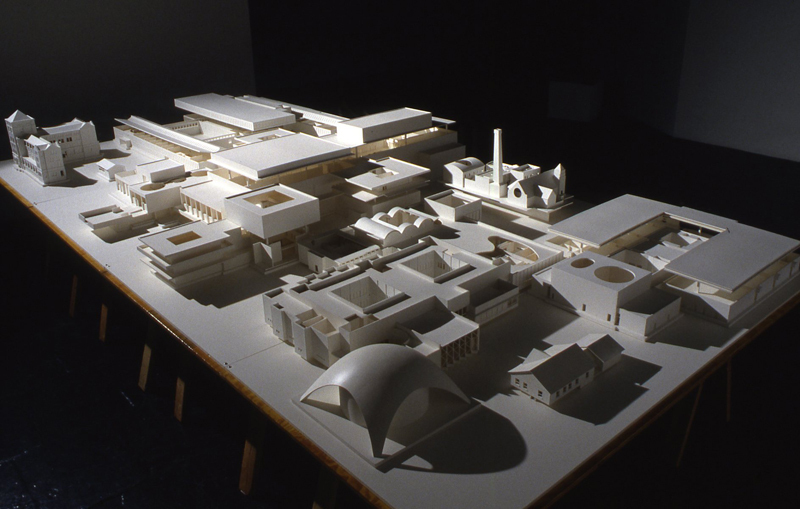

Jones was particularly taken with Educational Complex (1995), an architectural maquette that connects together models of every school Kelley ever attended, as well as Kelley's Kandor series. These glowing resin models are recreations of Superman's home-world's capital, which was miniaturised by one of the hero’s enemies and now is kept – according to the comic's narrative – in Superman's Arctic retreat, The Fortress of Solitude.

“These moulds of various sizes are illuminated in colour-tinted bell jars and are seemingly connected to oxygen tanks and power sources,” Jones writes. “Every aspect is electrifying.”

In all, the press seems to agree that this retrospective, which was first shown with a slightly smaller selection of exhibits at Amsterdam's Stedelijk Museum last year, serves as a fitting summation of a great contemporary artist's career.

{media1}

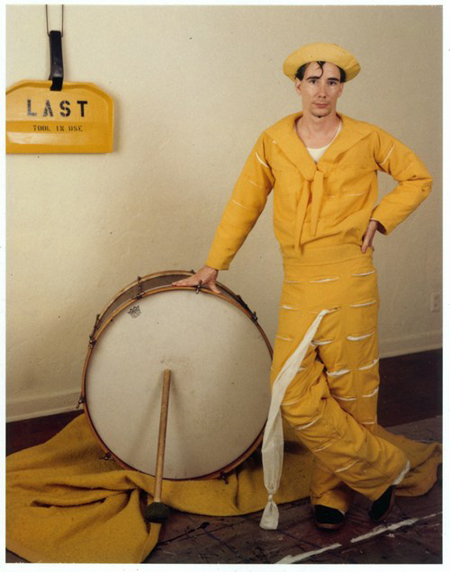

Visitors to PS1 yesterday even got to take in a performance of Kelley's heavy metal dance piece, Pansy Metal/Clovered Hoof, wherein the choreography of Kelley collaborator, Anita Pace, meets the meaty beat of Motorhead's 1986 classic, Orgasmatron. If you missed it, watch this video, shot at the Dutch retrospective.

To find out more about the PS1 show, go here. To learn more about Kelley's life and work, consider our book, which includes a great overview of the iconoclastic artist's often outlandish work, as well as some wonderful passages of writing by Kelley himself.