Niki de Saint Phalle's joie de vivre - and violence

First Spanish retrospective for pioneering feminist artist opens at the Guggenheim Bilbao next month

The joie de vivre – not to mention the violence – inherent in Niki de Saint Phalle’s huge body of work are just two of the conflicting artistic elements celebrated in the first ever Spanish retrospective dedicated to the artist next month at the Guggenheim Bilbao.

Covering a broad range of work including paintings, sculptures, prints, performance works and experimental films, the Guggenheim show (February 27-June 11) depicts an artist who inhabited a singular creative universe and one who pushed out the boundaries of art and feminism in her practice.

The pieces in the show, arranged in chronological order and according to subject, address recurring themes in the French born, US-resident artist's creative trajectory, such as the power of the feminine and open defiance of social conventions. In her work, de Saint Phalle combined her intense political and social engagement and her radicalism with colour and optimism.

In 200 works and archive documents, the show acknowledges the inspiration of Gaudí, Dubuffet, and Pollock while placing centre stage her pioneering work as the first major feminist artist of the 20th century, one who challenged norms and promoted the power of women and their role in society.

As Helena Reckitt writes in our Art and Feminism book, “women artists played a significant role in the art forms that emerged in the 1960s. Happenings, Fluxus, and performance sought a discursive, interactive relationship between artist and spectator; new conceptual frameworks emerged, informed by gender awareness. Women artists began to intervene directly in male-defined social and political spheres, articulating frustration at the injustices of domination.

Niki de Saint Phalle was at the forefront of it all and the Guggenheim retrospective features a number of her projects included and discussed in Art and Feminism.

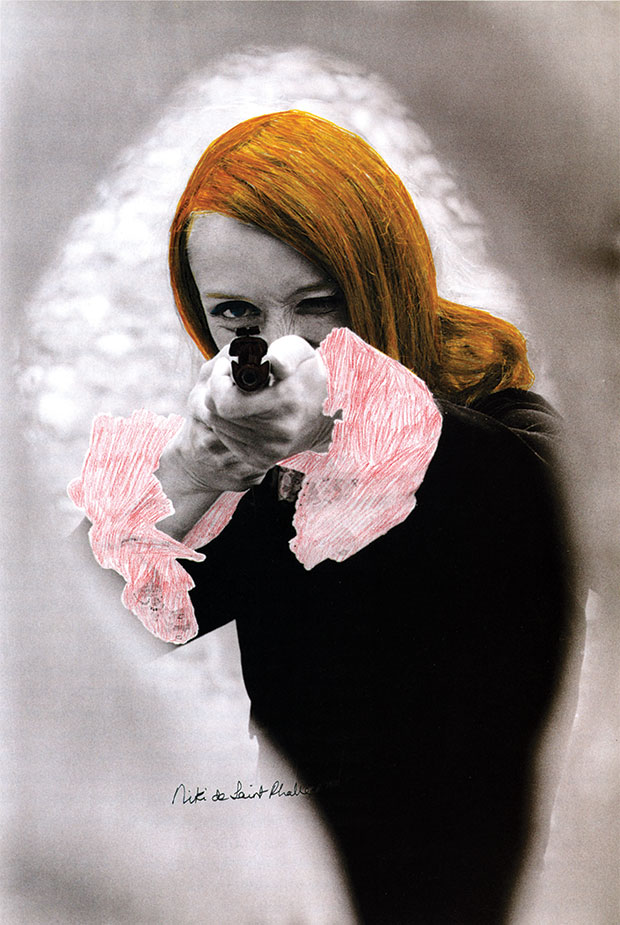

One of them, Tir a Volonté (Fire at Will), was a series of works de Saint-Phalle made in which she attached bags of liquid pigment onto white relief surfaces. These burst when they were fired at with a .22 calibre rifle by herself or others (including artists Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg). These shooting paintings, as they came to be known, aimed an attack at the traditional views of art, religion and patriarchal society as well as at the political situation that entwined the Cold War.

"Painting calmed the chaos that shook my soul," de Saint Phalle said. "It was a way to tame those dragons that have appeared throughout my work. I was lucky to encounter art, because I had, on a psychological level, all it takes to become a terrorist. Instead of that I used the rifle for a good cause - that of art."

The works were first exhibited at Galerie J, Paris, in 1961. As Reckitt writes in Art and Feminism, "The smoke gave the impression of war. The painting was the victim. The new bloodbath of red, yellow and blue splattered over the pure white relief metamorphosed the painting into a tabernacle for death and resurrection.” Niki de Saint Phalle went on to hold 20 shooting sessions over ten years. Looking back on the works, she said: “I was shooting at myself, society with its injustices. I was shooting at my own violence and the violence of the times. By shooting at my own violence, I no longer had to carry it inside me.”

To the casual observer of course, Niki de Saint Phalle is perhaps best know for her Nanas. These colourful feminine figures were initially made of papier collés and wool, and later of resin. They were a natural extension of the idea of fertility goddesses and births. She said the women were inspired by a drawing she did with Larry Rivers of his pregnant wife, Clarice.

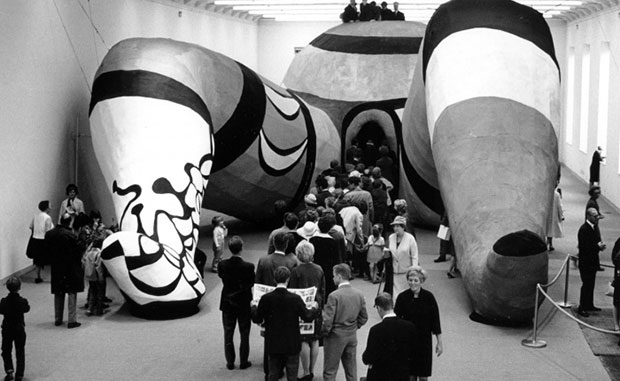

One of the most infamous, Hon, meaning ‘She’ in Swedish, was constructed as a temporary monument at the Moderna Museet, Stockholm, 1966, in collaboration with Jean Tinguely and Per-Olof Ultvedt.

As Reckitt writes in Art and Feminism, “visitors entered the gigantic , vividly multicolored female figure through the space between her legs, finding themselves inside a warm, dark ‘body’ that contained among other features a bar, a love nest, a planetarium, a gallery of ‘suspect’ artworks, a cinema and an aquarium.

Evolving from the earlier small-scale Nanas, _Hon _playfully paid homage to ancient and modern mythical archetypes of women as nurturer, while simultaneously demythologizing notions of the female body as a place of dark, unknowable mysteries.”

You’ll find more about the show here and you can buy Art and Feminism here.