Ten questions for Edmund de Waal OBE

The celebrated potter takes a moment to talk about his exquisitely designed monograph, a new project with David Chipperfield, the myth of tactility and what's better - an OBE from the queen or being signed up by Larry Gagosian

Edmund de Waal's new monograph has a unique twist behind its exquisitely crafted embossed cover. Rather than boasting just one, high profile, arts writer or curator placing his work in context, instead it features inspired, and, as it turns out inspiring, pieces of text on him and his work by the likes of A.S. Byatt, Peter Carey, Colm Toibin and Toby Glanville - a superlative haul of literary talent, we're sure you'll agree. Behind that cover you'll also find a number of perfectly reproduced photographs that capture the life and work of this most special of artists. To mark its publication, we sat Edmund down and asked him what he thinks of it (clue, 'he's beyond pleased'), what he's working on right now, what kind of china he drinks his morning cuppa from and what's actually better, an OBE from the queen or being signed up by Larry Gagosian.

How did you feel when you saw the writers' texts for the first time? It's a delight to get writers who you've been reading for an age so to find something of yours refracted into their writing is doubly incredible. Really, the biggest surprise was to be taken seriously by people you respect! But it was the diversity of the kinds of writing that pleased me most. Conventional monographs are often very staid and pedestrian in that they have one person writing in one tone, from one point of view - it can feel like a butterfly being pinned down in a cabinet. What was really lovely about working on this book was the unexpectedness and serendipity of different voices and different perceptions and fragments of poetry and references and turning ideas into fiction – that’s kind of like the way I work in my own practice. The other thing is, of course, when you read about yourself it’s very generative of ideas, so immediately it makes you want to go off and make things, or indeed write things. So suddenly you’re part of an ongoing conversation.

Were there elements of your work they picked up on that you were perhaps unaware of or hadn’t explored yet? Certain contextual things that I might not have put together were intriguing. And aspects. For instance, Peter Carey writes about ‘yearning’ in his text – which is a great word! That sort of brought something into focus that I’d been working around for such an age. And it was just so poignant and lyrical the way he did it. A.S. Byatt’s writing was passionate and forensic at the same time which is an aspiration anyone would want to have for their own writing. And when her gaze comes upon your work it’s kind of scary because you know she’ll say exactly what she thinks. But it is wonderful.

Carey’s idea of yearning, along with rhythm and repetition is one of the very many human aspects in your work isn't it? It’s absolutely that. It’s interesting, with this book there was this idea of almost curating a show. So it’s not a conventional anthology of text, it’s not a conventional monograph of someone’s life, it’s not a gathering of friends saying nice things, which is one of the other dangers of art books. It’s genuinely lots of different approaches going around a body of work. And I think that generosity comes out in the scale of the book really. It’s not so big you can’t lift it but it’s got a lot in it. And you can dip into it. I’m beyond pleased with how it turned out.

Do you think you’re maybe more in dialogue with poets, writers and musicians than you are with other visual artists? Well I hope I am in dialogue with lots of diverse things. The visual artists I’m most in dialogue with are architects - and possibly photographers, actually – so my hope is that I don’t fit in into any particular niche, really. The fact that I am a writer as well as an artist - one person who does two things is perplexing for some people. They kind of want to police me a bit more. And that’s fine if they want to do that. But categories don’t matter in the slightest because actually the real experience of reading something or seeing an installation or being in a building where there’s an exhibition isn’t a one liner. Why can’t you respond in terms of music or poetry or in terms of a critical text? That’s such a bollocks way of putting it, I’m so sorry! OK. Actually I think it’s a status thing. There is still an element where people go ‘but he’s a potter’. I’ve always been so proud of being a potter and saying 'I’m a potter' but that 'I’m going to work with museums and galleries and make texts and be up in the air and talk to contemporary musicians, and poets'. It’s always appealed to me but for some people it’s problematic because they still think that potters should belong in a little box.

Do you have a favourite piece of mass produced crockery? Analysing how you respond to objects is a really truly complicated thing. But I’m trying to think of what I might go for... OK it would have to be the crockery that I use every day. It’s by David Mellor and it’s the fine bone china. It’s what I eat cereal from in the morning and when we moved into the new studio that’s the china I demanded that we have for our day-to-day use. It’s actually very, very acutely done. It’s very kind china in that it’s the sort of china where someone has really thought about human beings. It’s not posh but it’s absolutely lovely for food and sharing and ordinary life in regards to its weight and the scale of it. It’s based around real people.

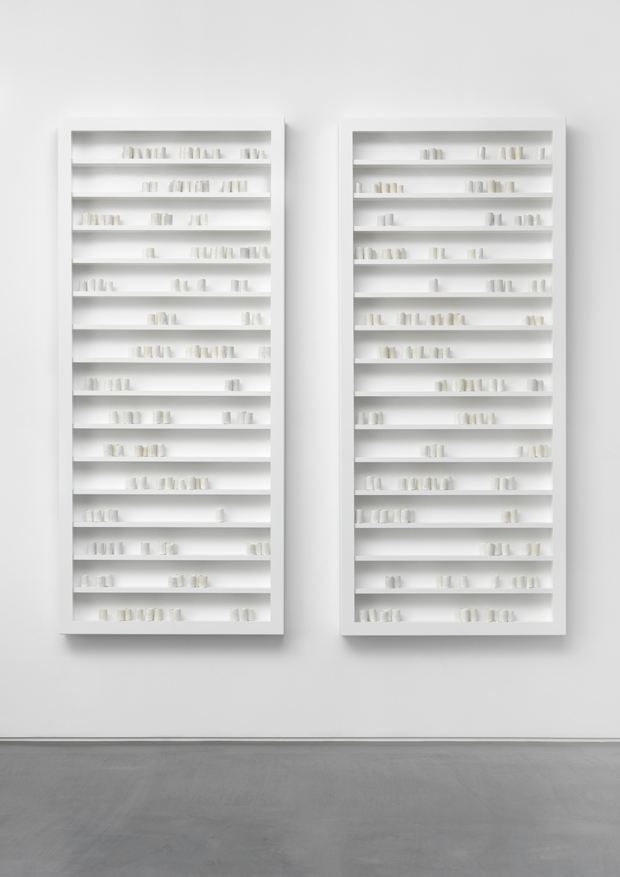

Is there a tension between the tactility of what you create and how that might be lost when it’s placed in a gallery or space because one can’t actually touch it anymore? Well, there are several elements to that. There are huge and powerful histories about not touching things and they exist too in pottery. A thousand years ago walking down a corridor in The Forbidden City there would be a hundred beautiful bowls in a row that you wouldn’t be able to touch but each would be symbolic of a particular thing. Or in the palaces of 18th century Dresdon there were walls of porcelain that were meant to inspire wonder and awe. So there have always been places where porcelain has been used poetically to express something about scale and wonder and ineffability and the elsewhere. It’s been used to express an idea of something beyond the immediate. For me when I put something 60 feet up in the air they are not touchable but they are completely present in the imagination and that for me is as strong as picking them up. So there’s that element and then there’s desire - not everything in the world has to be or can be picked up. It doesn’t have to be in your hand to have tactility.

As you become more famous (and your work gets more expensive) how have the emotions changed when somebody buys a piece, what do you feel now? Relief! Still. Really, it’s not about selling the stuff, it’s about getting it out of the studio. It’s about making space for the next thing you want to make. It’s nice if people like it but the critical thing is that it’s out the studio, that it’s living somewhere else and gets a chance to be looked at and thought about and encountered. You put an object down in front of you and you start to tell a story. So each time you put something down in the world it’s got the possibility of starting stories and beginning narratives with other people. I don’t make hermetic artwork. I hope I ‘open’ artworks, and then walk away.

__And what have other people put down or opened that you’re walking with at the moment? __ Well I’m halfway finished writing a book about the colour white. So as I walk around my book room now the things that I’ve got up are Malevich’s white teapot that he did after the Russian revolution, I’ve got a map of 18th century Cornwall up, I’ve got Invisible Cities by Italo Calvino, which for me is all about how do you ever finish a book. And I’ve got some 1200-year-old glazed shards of broken pots that I picked up on a hillside. They were evidently pulled warm by someone from the kiln and chucked over his shoulder because they’d all gone wrong. Each one I pick up I know everything that’s gone wrong with it - because it’s all happened to me!

What was better - getting an OBE or being signed up by Larry Gagosian? Ha! I can’t put those two things together. They’re not in the same world of oddness and experience at all. The OBE thing was a lovely family day. What I was really pleased about with the OBE was that it was for being an artist, it wasn’t for all this writing malarkey - and that felt really good, actually. That felt like the thousand hours had been noticed.

And what are you working on right now? I’m working with David Chipperfield on a project in Victoria, central London at Portland house. I’m doing a series of underground vitrines, which are almost like lift shafts, going down into the ground at different heights. It’s about memory and place but absolutely about bringing something very humane back into a complicated urban experience and having things for free in the streets of London where everything is very commodified and posh.

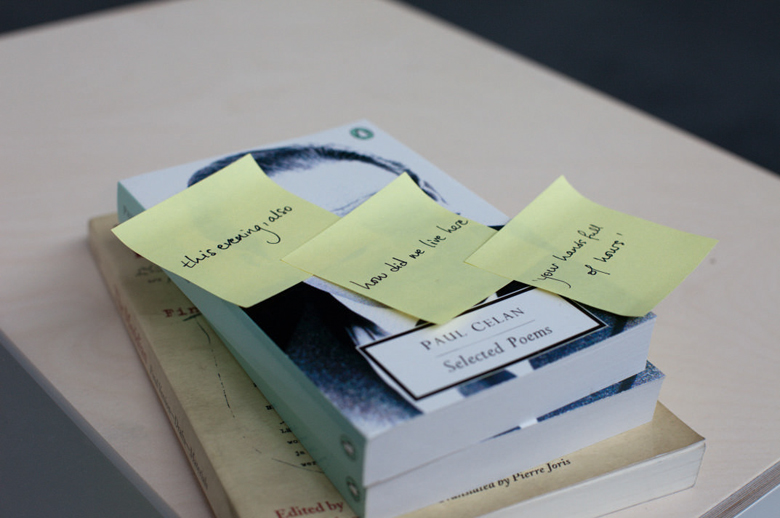

And there’s a new piece which is opening at the amazing 1820s neo-classical Theseus Temple in Vienna on Monday (April 28). It’s one installation, a pair of vitrines based around a poem by Paul Celan. The temple was built for a Canova sculpture which is no longer there. As you can imagine, Vienna is a hugely complicated place for me to work and so what I’ve done is my version of a poem by Paul Celan, and it’s a very spare and kind of austere, tough piece really in this very beautiful temple. It’s about the difficulty of moving towards the light. And Celan was just obsessed with how few words you had to use in order to write a poem. It’s almost about nothing at all but at the same time it's deeply complicated with a series of really tough words.

Check out Edmund de Waal's new monograph and his The Pot Book in the store. And take a listen to the music Edmund plays when he's working in his studio.