Chris Burden R.I.P.

Following the US artist's death on Sunday,we examine the key pieces that made him such a unique talent

It was F. Scott Fitzgerald who wrote “there are no second acts in American lives.” Yet looking back at Chris Burden’s body of work – as quite a few of us have been, since the US artist's death on Sunday, at the age of 69 – it is hard not to describe two distinct, and distinctly successful periods in his work.

There were the early, infamous performance pieces, and the later, more contemplative, sculptures and installations. As the Art Newspaper put it, Burden was “the artist who traded daredevil performances for daring engineering.”

However, perhaps there’s a common thread between the later pieces, such as his frenetic, model city, replete with racing cars; his solemn, antique lampposts; and his thirty-foot self-navigating sailing boat, and the early works, which focused much more closely on the artist’s body.

As many have noted, “Power was a central motif in Burden’s work.” Indeed, in his art, he examined the power wielded by industry, commerce, the church and state, but also exerted a certain power over his audience. Nowhere else is this as clearly expressed than in his most famous work, Shoot, which the artist performed in a 1971, at a small gallery in Santa Ana, California.

As we explain in our book, The Artist’s Body, Burden arranged for a friend to shoot him in the arm with a .22 calibre rifle from 15 feet away. The slug only grazed Burden’s left arm, yet he claimed that gallery goers were implicated in the act, by simply standing by and allowing Burden to take a bullet. The work took in wider events in the US: the Pentagon Papers had been leaked to the New York Times earlier that year, detailing the government’s long and crooked involvement in Indochina, while Burden’s gallery was within the Greater Los Angeles Area, home to the US film industry.

Yet the performance also had a personal bearing. As Burden explained to curator and friend Paul Schimmel in 1988, he undertook Shoot to gain “knowledge that other people don’t have, some kind of wisdom. How do you know what it feels like to be shot if you don’t get shot?”

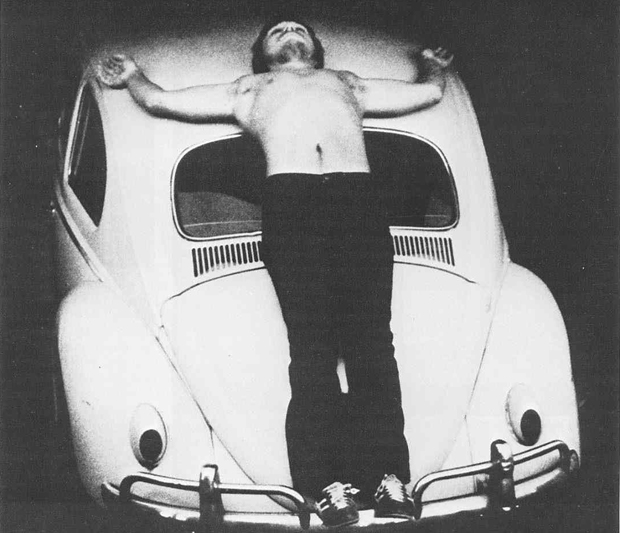

This alloy of self-knowledge and social commentary was apparent in another little-seen, though widely referenced performance, which also appears in The Artist’s Body. For his 1974 piece, Trans-Fixed, “Burden stood on the rear bumper of a blue Volkswagen Beetle, laying his body on the car and stretching his arms over the roof. Nails were driven through his palms and the car was pushed from the small garage out into the street. For two minutes the engine was run at full speed, ‘screaming’ for the artist, before the car was rolled back into the garage.”

“Burden punned on religious-spiritual experience, countering the intensely emotional resonances of the word ‘transfixed’ with a live, physical enactment of a real transfixion in the form of a crucifixion. Placing himself in a quasi-religious context, Burden presented himself as a modern martyr to contemporary consumerism as represented by the cars in California’s burgeoning freeway culture.”

It was difficult, painful, pioneering art like this that earned Burden his place within the contemporary art world and, now, in art history. As he told interviewer Robin White in 1978, “I often think of myself as sort of training for some sort of – you know, outer-space programme. I mean, I feel like, in some way, I’ve done some of the same things.”

He may not have explored space, but he did explore the extreme outer reaches of the American Century, and for this we should all be grateful. To find out more about this important artist, take a look at The Artist’s Body, here.