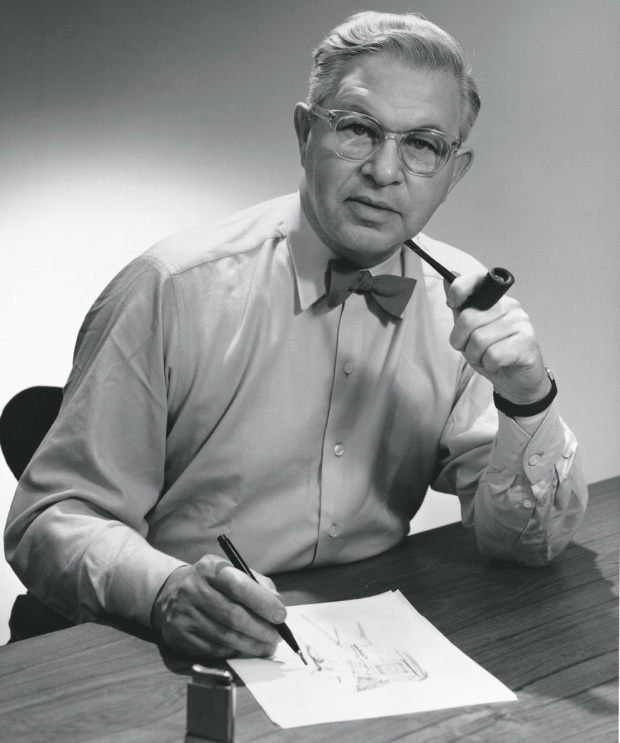

Arne Jacobsen - Architect, designer... gardener?

we look at how horticulture and the natural world helped inform some of this great Dane's best-known creations

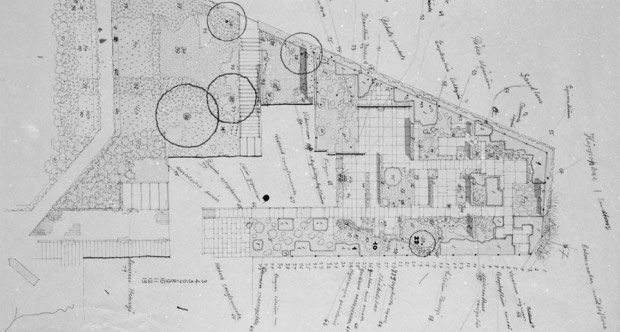

St Catherine’s, beside the the River Cherwell in Oxford, is the only 20th century college within Oxford University to be granted Grade I listing by English Heritage. This level of protection, the highest possible under UK law, not only places the building on an equal footing with Big Ben and Buckingham Palace, but also extends to St Catherine’s fixtures, fittings and its garden.

Asthetically, these beautifully arranged lawns, water features and trees are certainly worth preserving. Yet the horticulture has a historical significance, as is explained in our book, Room 606. The grounds of St Catherine remain architect, designer and gardener Arne Jacobsen’s “most literal creation of an artificial landscape.”

Though best-known for his mid-century furnishings and beautifully conceived modernist architecture, Danish-born Jacobsen’s creative life was deeply informed by the natural world.

“His earliest use of nature as a wellspring for creativity was the watercolour plants and landscapes that he painted as a child, the legacy of an artistic mother who practiced botanical illustration,” writes Michael Sheridan in our book. “As an adult he became an obsessive and skilled gardener, both personally and professionally, using his garden as a laboratory for colour and texture."

Jacobsen, who was born on 11 February, in 1902, graduated from the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts’ architecture school in 1927, and spent the first decade of his career designing the houses and grounds for the country’s burgeoning garden suburbs.

These modest family dwellings, built to accompany the development of Denmark’s highway system, may not have been particularly ambitious, yet they did allow the young architect to develop his techniques for integrating the natural world.

“Jacobsen removed any hint of ornament and rearranged the windows to increase natural light and views of the surrounding landscape,” Sheridan explains. “As he reduced the traditional house to its essential form, Jacobsen added projecting wings, arbors and terraces that extended the living space into the site, and by the early 1930s, he was designing the house and the garden as a unified composition.”

World War II forced Jacobsen into exile, yet when he returned to Demark, he had developed a clearer sense of how architecture and horticulture might best be integrated. “As his buildings shifted towards asymmetrical compositions of unadorned planes, their interaction with their surroundings became increasingly direct. While Jacobsen continued to design gardens for his buildings, those gardens took the form of planted courtyards or stepped terraces.”

In the early drafts for his greatest work, the SAS House in Copenhagen, Jacobsen attempted to bring the natural world right into the building.

“The final planning study,” writes Sheridan, “included a pair of gardens that framed the hotel lobby at the base of the tower. Enclosed by walls of glass, the twin gardens would have created a transparent base for the tower. A lounge above the lobby connected the gardens, while a glass bridge leading to the hotel restaurant would have created a path through the treetops.”

Jacobsen even a tree-like fixture in the SAS’s lounge, clustered with light bulbs, just as the branches are illuminated in the nearby Tivoli gardens.

While the SAS’s winter gardens never came to pass, other creations by the great Dane, such as St Catherine’s still stand as a testament to his landscaping skill, and a demonstration of how the Modernist, Mies-style architectural blocks can still engage with the natural world.

For more on Jacobsen get Room 606 and for more on beautiful horticulture around the world buy The Gardener’s Garden.