Why Mies van der Rohe divided opinion

Genie behind the curtain wall or architect of cold technology? Let Detlef Mertins guide you to the answer

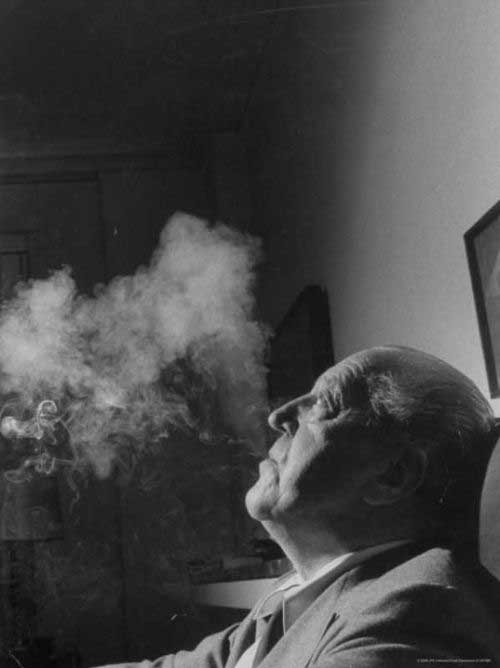

Spanning sixty years, two continents and two world wars, based first in Berlin and then in Chicago, Mies van der Rohe’s career was a complex one, marked by discontinuities and struggles as much as continuities and success.

Little wonder then that our new book, Mies – pretty much consumed the final decade of its author, curator architect and writer, Detlef Mertins. Mertins read everything written by and on Mies van der Rohe, travelled to all of his buildings and conducted an incredibly detailed study of the architectural, philosophical and scientific literature in Mies' own libary. To describe the book that sprang from all this research as merely 'exhaustive' is to bring new meaning to the word understatement.

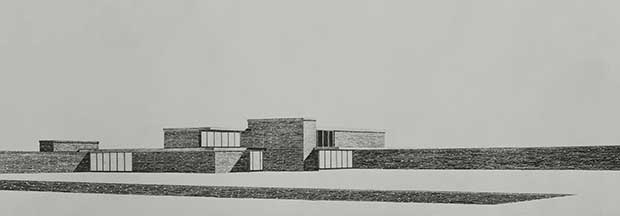

As Mertins writes, in retrospect the trajectory of Mies van der Rohe’s career was less inexorable and more contingent upon changing contexts, challenges, clients and collaborators. While there are certainly continuities between them, how different the Farnsworth House in Plano, Illinois (1945–50) is from the Barcelona Pavilion (1928–9), and even more so from the Esters and Lange houses in Krefeld (1927–32) or the earlier Werner House in Berlin-Zehlendorf (1912–3).

Heralded in his lifetime as the heroic inventor of the all-glass skyscraper – the genie behind the curtain wall, master of modularity, philosopher of perfection – Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (1886–1969) became, for critics of modernism, the destroyer of familiar traditions and the architect of cold technology and faceless bureaucracy. He had been attacked by conservatives throughout his life, but beginning in the 1970s, a younger generation of progressive architects and critics sought to define themselves in opposition to him. He was called boring, anti-historical and authoritarian. Urbanists riled against the destruction of the traditional city and the endless proliferation of neutral glass boxes for which he seemed to stand.

Having been cast as a leader of the ‘International Style’, Mies was later held responsible for creating the universalizing modernism carried by his followers into the corporate boardrooms of America and disseminated from there to the far reaches of the globe. For social critics the spacious elegance and material sumptuousness of Mies’s buildings were no longer appreciated for redeeming instrumental rationality but were seen to aestheticize the alienation, exploitation and dehumanization of mass society.

Yet Mies gradually re-emerged, and by the turn of the millennium he was widely celebrated once more, not only as a looming figure of the twentieth century but also as an active presence in contemporary architectural culture. Having defined modernism of the post-World War II period more than any other architect, Mies served to inspire a renewal of modernity after postmodernism and was in turn reborn through it. Like this new modernity, Mies has become more complex and contradictory, less black or white; in fact he now appears both black and white, dark and light, complicit and resistant, classical and modern, ordinary and extraordinary.

Today it is possible to see him as part of an alternative stream within modernism, amongst those who produced unresolved contradictions, excluded middles and active – if not corrosive – compounds. Like Marcel Duchamp, whose Door: 11, rue Larrey (1927) is both open and closed, Mies is an architect of sustained dualities.

Unlike Duchamp but like his friend Kurt Schwitters, Mies sought to mediate opposing categories, to subsume and transform them in works that could be said to move towards a synthesis or system, in the sense of the Romantics. Whereas Ezra Stoller and Hedrich-Blessing produced with their iconic black-and-white photographs an heroic image of a tough, crystalline and objective architecture – autonomous objects with sharply chiselled profiles – more recent photographers and photo- based artists have been drawn to the colourful, luminous, ethereal and blurry qualities of Mies’s work, its darkness and at times even its ordinariness.

Mies’s oeuvre now appears more relentlessly experimental, even as he was driven to monumentality. His works are, he once said both progressive and conservative. They are monumental experiments and experimental monuments that hold together as a sustained quest; a lifelong effort to forge a new architecture that would be adequate to the evolving history of modernization and the philosophical and cultural exchanges it raised.

This is but a small taster from Detlef Mertins’ definitive Mies van der Rohe book Mies, available in the online store now.