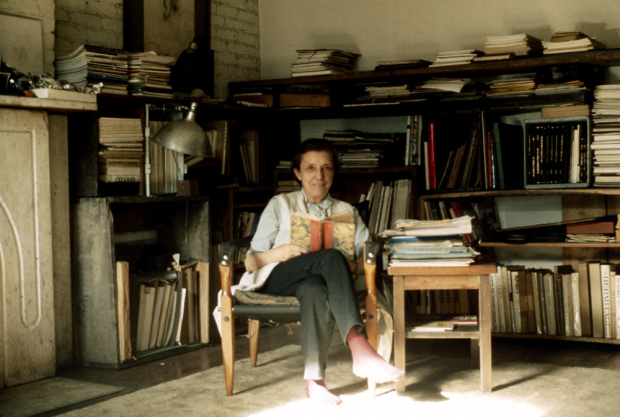

At home with Louise Bourgeois

What to expect when the West 20th Street townhouse where the artist lived and worked opens for tours this year

Domesticity could be both terrifying and beautiful for the French artist Louise Bourgeois. On 12 October 1938, at the age of 27, she moved from Paris to New York to join her husband, the American art historian Robert Goldwater.

“There Bourgeois entered the innermost circles of the period’s advanced culture,” writes Robert Storr in our monograph. ”Among the writers, scholars, critics and curators she met and soon got to know intimately were Jacques Barzun, Henry Russell Hitchcock, Mary McCarthy, Erwin Panofsky, Meyer Shapiro, Edmund Wilson and, perhaps most significantly, Alfred Barr, the founding Director of the Museum of Modern Art.”

Yet life in this new city was not without its difficulties, as Storr makes clear. “Caught up in this whirl, in love with a man who was utterly dedicated to his scholarship, and homesick for France, Bourgeois experienced a profound disorientation which she tried to remedy by plunging into the role of mother and wife.”

The domestic, familial and material concerns may have stymied the artist’s career at points, yet they also fed her creatively, serving as a wellspring of deep, psychological inspiration for Bourgeois right up until her death in Manhattan, on 31 May 2010, at the age of 98.

Later this year, art lovers will get the chance to visit the site of this domestic and artist foment, when Bourgeois’ Easton Foundation begins tours of the West 20th Street townhouse that the artist and her husband bought in 1962. The house has remained largely untouched since her death; her clothes still hang in the wardrobes, and her TV is as she left it. Goldwater’s personal library also remains unaltered on the building’s third floor. Yet the home is really Louise’s, not least because she lived there for so much longer than her husband.

“Upon Goldwater’s death in 1973, Bourgeois rearranged the domestic spaces of the home and expanded her studio practice from the basement to the parlour floor, transforming the whole house into a work of art,” the Easton Foundation explains. “It is here that Bourgeois realised many of her sculptures, drawings, and prints, as well as conceived of large-scale projects and commissions.”

Bourgeois established the Easton during the 1980s, and, upon her death bequeathed to this non-profit organisation a wide selection of her art, as well as this enviable piece of real estate, which not only served as her home and studio, but also hosted Bourgeois’s famous Sunday salons, where artists, writers and curators would share their work and ideas.

Given the modest, and delicate nature of the home, and Bourgeois’ ardent following within the art world, the Easton is figuring out how to best open the house to the public. Having announced its intentions earlier this year, the Easton says details of the tours, which will be ticketed and require advanced reservations, will be posted in due course on its site. For more go here, and for more on this brilliant sculptor buy a copy of our Bourgeois monograph here.