Stuart Davis – Proto Pop artist or Modernist master?

Or perhaps even a Cubist as William C Agee, the author of Modern Art in America 1908–68, argues . . .

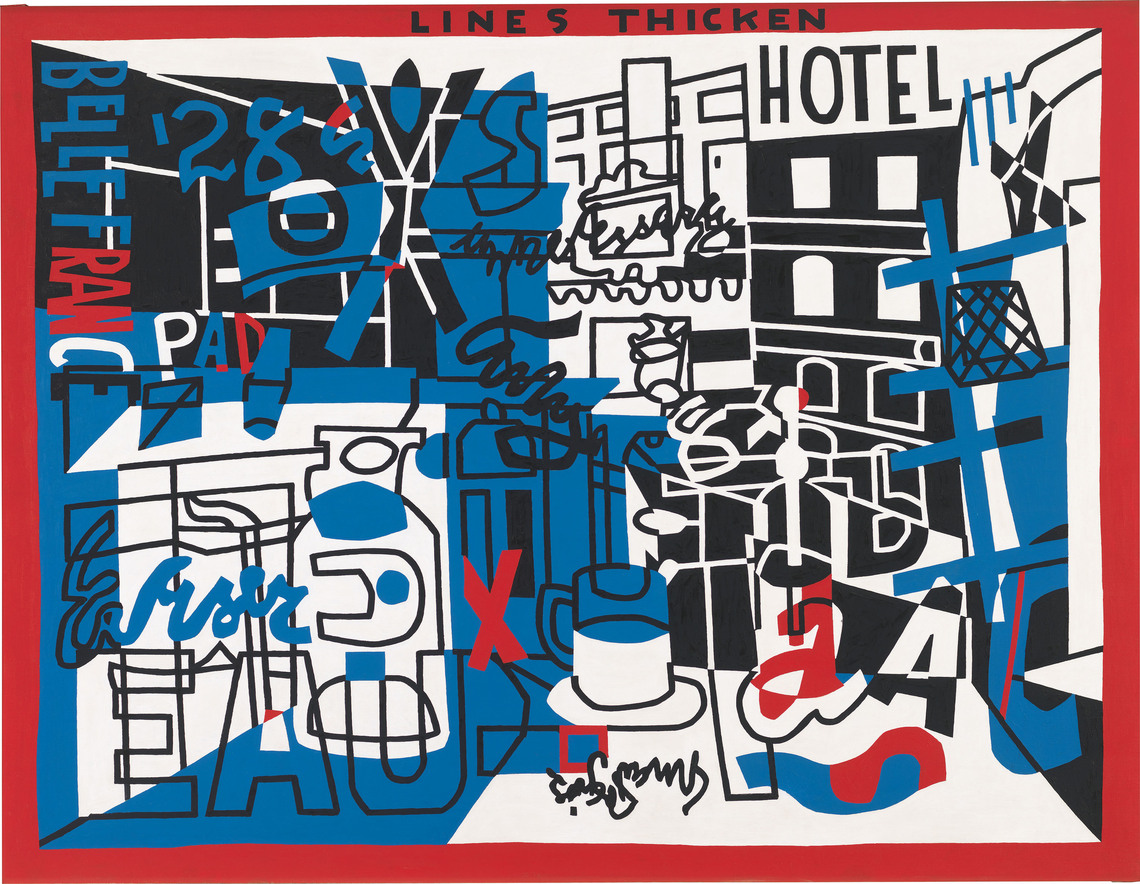

The Whitney’s current exhibition Stuart Davis: In Full Swing, is a treat for fans of American painting. Who knew that Modernism took root and flourished so early on the Western shores of the Atlantic? Well, the author and academic William C Agee, for one. His book Modern Art in America 1908–68 makes a strong case for America leading the way in Modernist circles well before the end of World War II. A good deal of Agee’s argument rests on Davis’s bright, geometric paintings. Here’s what you should know about Davis, in Agee’s words.

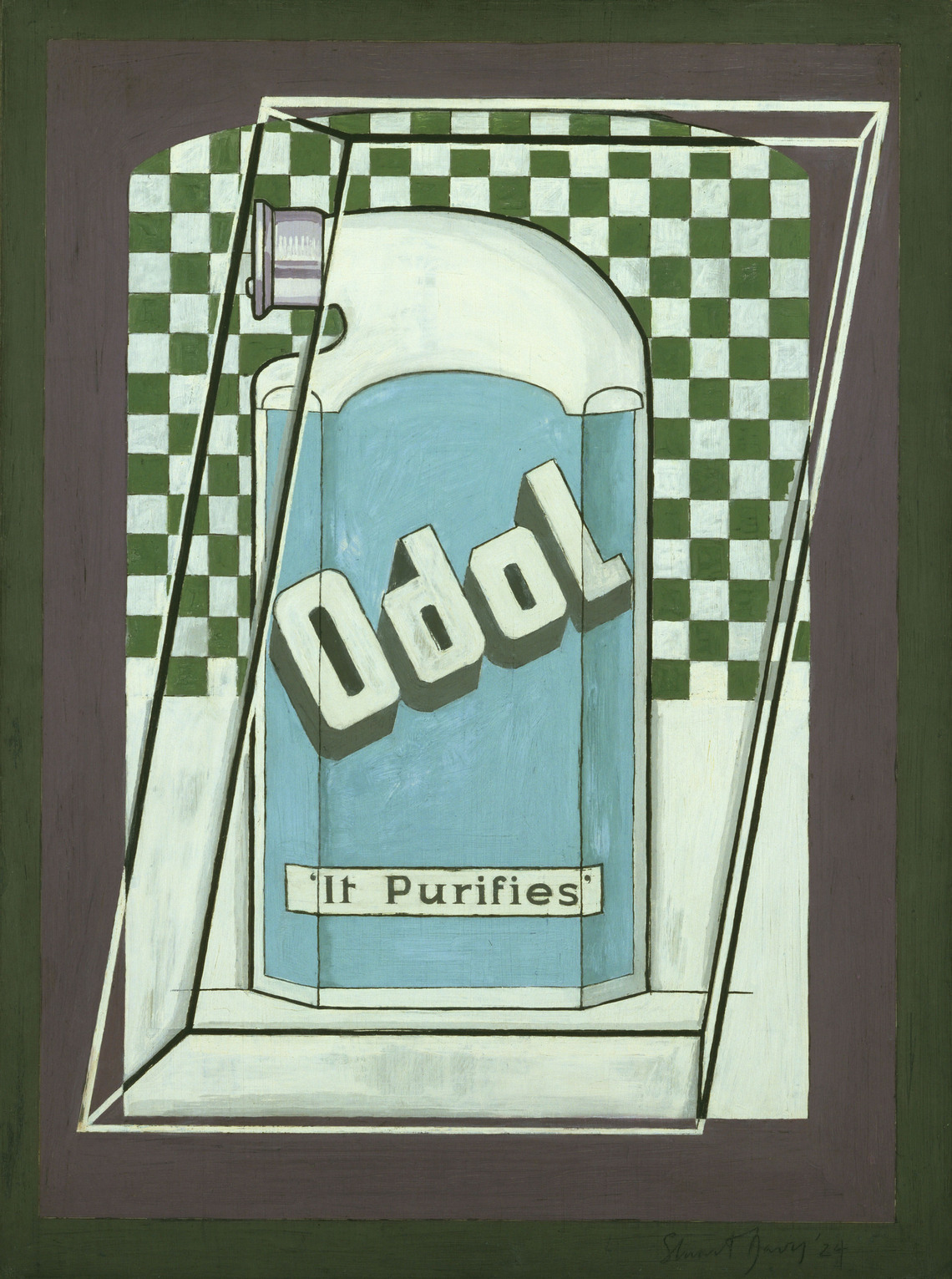

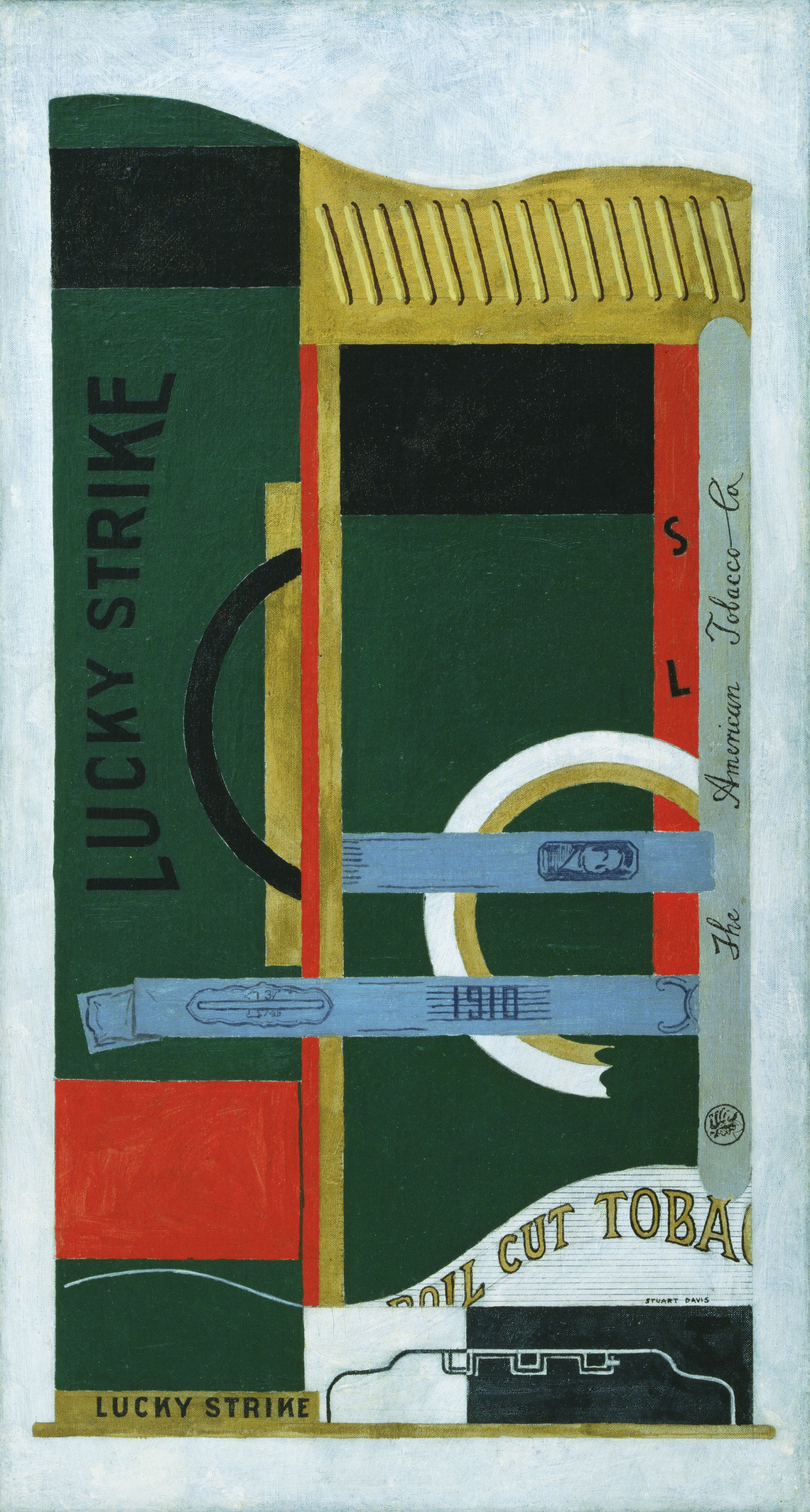

1) He painted packaging labels nearly four decades before Warhol did his Campbell’s Soup cans Davis tried his hand at reproducing commercial packaging in paint, partly as a stylistic challenge. For this reason, he’s sometimes regarded as a Pop predecessor. “Davis’s most famous use of commercial sources is Odol (1924), often the one painting used to illustrate the entirety of his art, and especially loved because it casts him as a kind of historical proto-Pop curiosity,” writes Agee. “This is in part true, of course, but it hides the real and full complexity of the artist.”

2) He was a contemporary of Edward Hopper’s and began as an Ashcan School painter Born into an artistic family in Philadelphia on 7 December 1892, Davis enrolled as a pupil of noted realist painter Robert Henri. Henri also had taught a teenage Edward Hopper, who was ten years Davis’s senior.

Both painters began as part of the Ashcan school, a distinctly gritty, US style of urban realism. The Ashcan School took its name from a 1915 drawing by George Bellows called Disappointments of the Ash Can. The term was used disparagingly by the cartoonist and writer Art Young in 1916, and later, in a more official capacity, in a 1934 exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art.

“Hopper and Davis could be said to be second-generation Ashcan artists, taken with the energy and drive of the modern American city, but now interested and alert to the more structural direction that contemporary art was taking," writes Agee. "They were also more attuned to human emotion and psychology.”

3) He was the youngest artist to show at the 1913 Armory Show – and the effect on him was huge Davis was just 20 when he exhibited a series of watercolours at this seminal New York exhibition. However, the influence of European Modernists works in the Armory Show by such artists as Marcel Duchamp, Pablo Picasso and Francis Picabia set him off in an entirely different direction. “The Armory Show was a bomb, but it was a not a ‘bomb that was unexpected,’ Davis said; not so much a challenge as ‘a boost to something I already felt.’”

4) He developed a distinctly American style of Cubism “In his famous ‘Egg Beater’ paintings of 1927-8, Davis reached a new height of complexity and achievement," writes Agee. "No other Cubist paintings are quite like these, and they should be recognized as genuinely American additions to world art. They ushered in a new type of distilled, lean geometric art, based on Cubism, that lasted in America until Mondrian’s death in New York in 1944.”

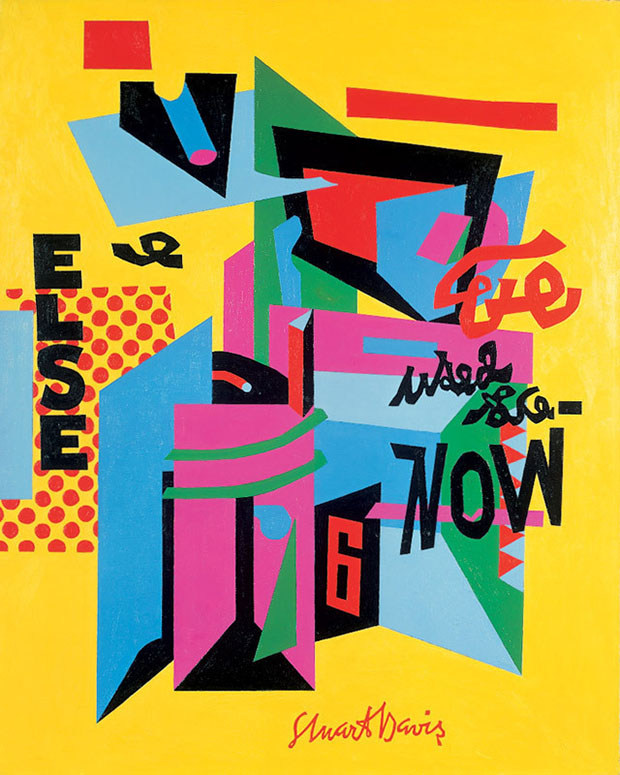

5) Drink nearly killed him, and sobering up brought on a brilliant, late streak Alcohol nearly finished off the artist off, just as abstract painting was taking over New York. “Davis had recovered enough from his near death episode 1948-49 to begin a new campaign of painting,” writes Agee. “He was well aware of Pollock, de Kooning and Kline, and understood them to be his most serious challengers, despite his apparent dismissal of Abstract Expressionism as a ‘belch from the unconscious.’” Now sober and with serious local competition, Davis was spurred on to create a series of brilliant, late paintings, admired by a much younger generation of artists. “There should be applause,” wrote the author and influential minimalist artist Donald Judd in 1962, after viewing a Davis exhibition. “At age sixty seven he is still a hot shot.”

For greater insight into both Davis and the remarkable and often misunderstood development of Modernism in America, get Modern Art in America 1908 – 68.