Renzo Piano on how to design a museum

As it nears completion, Piano explains why his new home for the Whitney will 'hit NYC like a meteorite'

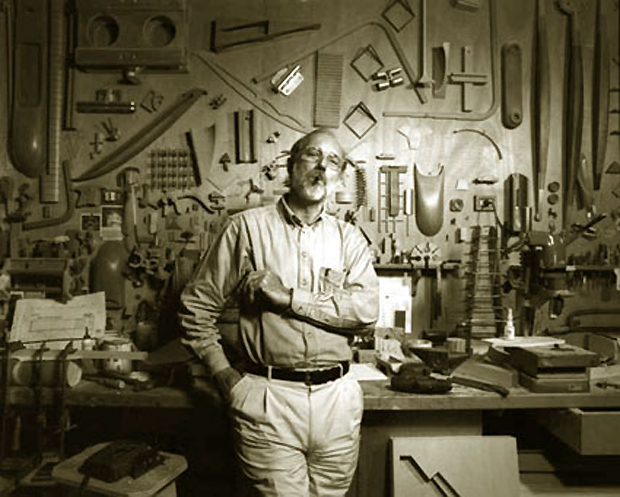

Few architects are better qualified to comment on museum architecture than Renzo Piano. The Italian Pritzker laureate has, as Metropolis Magazine’s Paul Clemence notes, designed 25 such institutions, 14 in the U.S. alone. During the final phases of his new building for the Whitney Museum of Art – due to open next spring - and his expansion of the Harvard Art Museums – opening to the public 16 November – Piano spoke to Clemence, describing just how he went from the maquette to finished museum space. Interestingly, Piano says he prefers to avoid digital design techniques, as the accuracy of computerised draftsmanship stymies spontaneity.

“With the computer you need to tell it exactly what to do,” Piano explains. “When I am doing the sketch, I don’t have to tell the sketch where to start, where to end. It’s instinctive. Sketching, like the model, has the quality of imperfection. Neither has to be precise. It gives you freedom. It gives you the possibility to change.”

Even once a design is in place, some change is necessary, Piano acknowledges. “As an architect you have to keep focus,” he says, “but you also have to have to listen. And to recognize the good voices from the bad voices, and that is very difficult because sometimes the important voices are hard to hear.”

The interconnected quality of buildings within a city is something Piano returns to repeatedly in the interview. A good building, he says, should be like a well-mannered, civic person, able to engage in dialogue and to share experiences. Yet, unlike us mortals, Piano’s buildings ‘fly’.

“They are rooted, but they lift up,” he says, “above the ground and that lets light come under and inside and allow the ritual of the city life to merge with the ritual of the building life. By lifting the building, the ground floor becomes almost a continuation of the public realm. You leave space beneath it for life to happen.”

Buildings, such as Paris’ Centre Georges Pompidou which Piano designed with Richard Rogers in 1971, can bring about a necessary change within a city, and a good architect should know how to manage that change, and the flak that comes with it.

“It took the Centre Pompidou 10-15 years to be accepted by the city,” he says. “The handicap of a new museum is just that, that it's ‘new.’ It has not yet gone through the ritual of day-to-day life in the city. It takes time for a building to be loved and adopted by the city. Whether it is a theatre, university, museum, or a church, the building has to become part of the daily life of the city to be accepted. Architecture is not something that is typically recognized or understood the first day. ”

So, what sort of change will his soon-to-be completed museums bring? Piano doesn’t comment on the likely effects of his Harvard work, but he does think the new Whitney will be “like a meteorite, but a gentle one. It does not destroy anything—actually it uplifts. But it lands, and it is something new there.” Let’s hope Manhattan is ready for impact.

Read the full interview here; and for greater insight into this important contemporary architect, buy Renzo Piano Building Workshop: Complete Works, a multivolume set. Meanwhile, for more on how we build today, sign up for a trial of the Phaidon Atlas, our peerless online architectural resource.