Terunobu Fujimori's teetering tea houses

Scholar turned architect featured in Atlas of 21st Century World Architecture opens innovative Munich show

In 1991, having worked for three decades as an architectural historian, traveling internationally on the look-out for architecture's great secrets, Terunobu Fujimori received a commission to design a small family museum. The then-44-year-old was apprehensive. Fujimori was respected as an academic, not as an architect, and if he were to accept the offer he knew the results would be called into question. Would his reputation be jeopardised if he now began to create the buildings he was supposed to be reviewing? And, perhaps more importantly, with such a vast knowledge of architectural movements past and present, exactly what sort of building should he make?

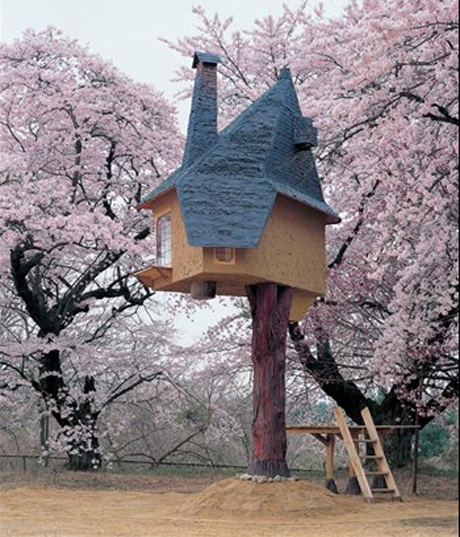

Fujimori eventually accepted the offer – the finished building, famed for its eccentric facade, was described by architect Kengo Kuma as "a punch of a kind no one has ever seen before in modernism" – and never looked back. In a pioneering professional career now spanning 20 years, the architect has produced two-legged teahouses suspended 20 metres above the ground; homes whose chimneys are planted with pines and whose roofs are covered in leeks and chives; and guesthouses that perch precariously atop small segments of white wall. Whereas his contemporaries – starchitects like Tadao Ando and Toyo Ito, who he counts as close friends – embrace Japanese simplicity, conceptualism and new materials, Fujimori prefers eccentricity, tradition, character and natural elements local to the sites at which he works (mud, wood, stone and, often, living plants). Imagine the 'weird and wonderful' end of the architectural spectrum, then discover Fujimori's work a good few points beyond it, somewhere near 'fairy-tale.'

Six years ago, the architect – at that point relatively unknown in the West, despite achieving a high level of celebrity in his home country – designed the Japanese Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, for which he asked visitors to remove their shows before climbing through its hole-like entrance. Since then a European audience has blossomed, culminating this week in a retrospective of his work to date at Munich's Museum Villa Stuck.

The highlight? A specially developed mobile teahouse which sits in the Villa Stuck gardens and that points to Munich's ever-growing cafe culture. (Teahouses play an important part in Fujimori's work – it's the one element of Japanese culture to which he consistently returns). There are other exhibits of note, too: his sketches, which the architect composes alone before revealing to a group of helpers (the Jomon Company, as he calls them, in a reference to the primitive tools they use); his intricate and eccentric models, often hacked into tree stumps; and various academic projects developed as part of his work with the ROJO collective, a group of "architecture detectives" who, since the '80s, have set about capturing "unusual but naturally occurring patters in the city."

The exhibition centres around Tokyo 2107 Plan, a hypothetical project from 2007 through which the architect presents a critical vision of Japan's future architecture, especially poignant now after recent earthquakes, tsunamis and the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster have called into question architecture's future role. It's an indication of the breath and ambition of Fujimori's practice. This isn't someone content with creating a few eccentric buildings – here is an architect who places architecture at the heart of social discourse, right where it should be.

You can find Fujimori's Roof House and his Too Tall Teahouse (built in his father's back garden incidentally) featured in Phaidon's Atlas of 21st Century World Architecture. The Roof House is especially interesting: the exterior walls consist of a black-and-white striped skin clad in carbonised cedar wood beams and plaster over a reinforced concrete framework. The roof, meanwhile, is clad with hand-bent copper tiles to create the appearance of a neo-primitive hut.

The Atlas is especially good on picking up and highlighting the influences in Fujimori's work, citing elements as diverse as sixth century Japanese temples, the Neolithic stones of Callanish in Scotland, Malian rammed-earth mosques and European thatched cottages.