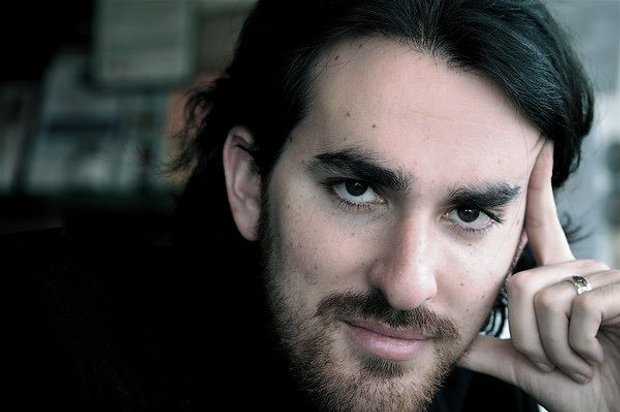

Foiling the Forgers with Noah Charney – Giacometti

How did a con man and a teacher strike one of the most successful forgery partnerships ever? Our author tells all

How did an English art teacher come to pass his paintings off as the work of the 20th Century modernist Alberto Giacometti? As Noah Charney, the author of our new book, The Art of Forgery, explains, John Myatt's success came down to painterly skill combined with documentary levels of deceit.

“Myatt is the best-known forgers of Giacometti, and also one of the world's most famous forgers,” explains Charney. “He even had a TV show where he taught people to paint in the style of other artists.”

However, Myatt's new-found fame stands in contrast to the dire straits he found himself in just before he began passing his work off as originals. In 1985, Myatt, then a 40-year-old English art teacher, had just separated from his wife and had to find way to both pay for and care for his young children. “He was a working single father who had trouble covering the bills,” Charney explains. “So, he advertised his services making 'genuine fakes' in the style of other artists for a couple of hundred pounds.”

Myatt's works, which he sold through the back pages of the British satirical magazine Private Eye, were not hugely profitable. However, one buyer was able to generate significant income from one of Myatt's paintings. “Someone called John Drewe contacted Mr Myatt,” Charney goes on, “and said he had bought one of John's paintings and sold it as an original.”

The work in question was a piece in the style of Albert Gleizes, a French Cubist, which Drewe managed to consign to Christie's, netting him £25,000. Myatt had charged Drewe just £150 for the canvas. Indeed, the sale is all the more surprising, since Myatt had not painted in the medium favoured by Gleizes.

“He didn't use oils,” says Charney. “Instead, he would use acrylic paints. So people should be able to tell the difference pretty easily.” However, Drewe had found a way to trick researchers into believing Myatt's painting was real, by placing phoney supporting evidence into real archives.

“It was another version of what I call the provenance trap,” Charney says. Rather than buy genuine works, produce a phoney copy, and sell it on with the original documents, as Ely Sakhai had done, Drewe went on to commission forged works from Myatt, then placed forged documents in real archives, attesting to the forged works' authenticity.

Wisely, Drewe did not encourage Myatt to produce a version of well-known pieces by the likes of Giacometti. Rather, he suggested Myatt make apparently unknown, minor works in the appropriate style. Drewe then placed his forged letters, receipts, and inventory notices relating to this apparently undiscovered work into the archives of such venerable cultural institutions as the Tate and the Victoria & Albert Museum.

“When a work is consigned to an auction house, researchers will look it up in the artist's catalogue raisonné," Charney explains. "If it can't be found in there, they will go to large, public and academic archives. Drewe would slip his documents in there, and the researchers would stumble upon what looks like a piece of documentary evidence.”

Indeed, junior researchers are apt to fall for Drewe's trap, because the discovery of a document that authenticates a new work is a prestigious find, and could further their own careers.

Myatt and Drewe kept their fraudulent scheme going for about a decade before they were finally arrested, Myatt in September 1995, Myatt, and Drewe in April 1996.

In total the police believe the pair passed off about two hundred forgeries throughout their working career; a damaging amount, not so for its detrimental effects on private collections and institutions, but more because of the way their scheme polluted the historical record.

“Most forgers are taking advantage of wealthy individuals and institutions,” admits Charney. “It doesn't go far beyond that initial financial damage. But in terms of something deeper and more problematic, by adding lies to a historical archive, you damage the degree to which people trust documentary evidence.” he concludes. “That's the greater crime.”

The V&A and other institutions have combed through their archives looking for these false insertions, yet it is hard to say when they will be free of Drewe's forgeries, even if Myatt's works have been consigned to the dustbin of history.

If you’d like to hear some of these forgery tales from the man himself try to make it along to Noah Charney’s East Coast author tour, at the start of next month. On Wednesday 3 June he will be giving a lecture and signing copies of his book at Kramerbooks & Afterwords Cafe (1517 Connecticut Avenue NW) in Washington, DC; on Friday 5 June Charney will be speaking and signing books at the Museum of Fine Arts (465 Huntington Avenue) in Boston; on Saturday 6 June he will be giving a lecture and book signing at the Institute Library (847 Chapel Street) in New Haven, Connecticut. On Sunday, 7 June he will give another talk and book signing at Gallery 25 and Creative Arts Studio (25 Church Street) in New Milford, CT; and on Monday, 8 June we are very proud to have Noah in conversation with the wonderful art critic Blake Gopnik 92nd Street Y (1395 Lexington Avenue) in New York.

You can see more over on our dedicated events page here. And you can of course, for more great stories from the history of art intrigue, buy a copy of The Art of Forgery.