Gombrich Explains Edvard Munch

The Norwegian painter, born today, 12 December, in 1863, detached fine art from its conventions, to great effect

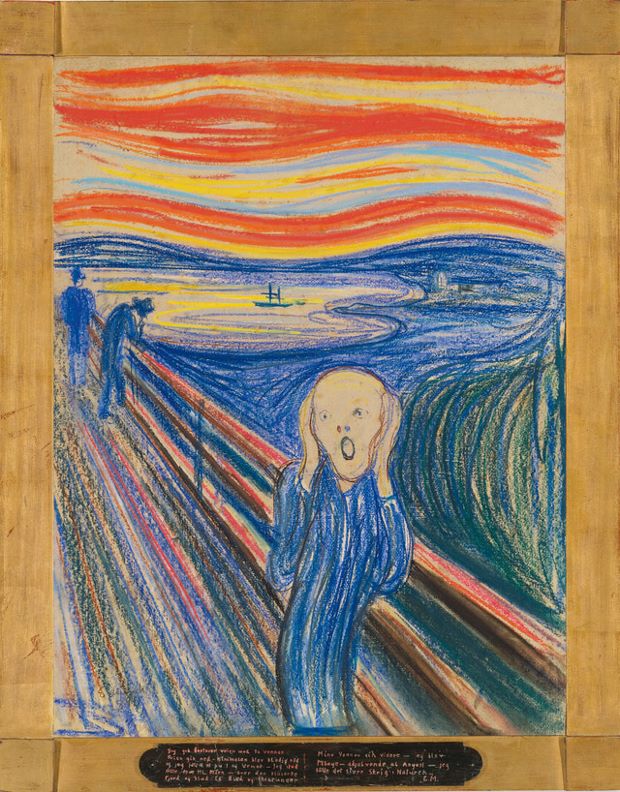

It’s one of the best-known paintings in modern art history. Yet why, today, 12 December, on the anniversary of his birth in 1863, should we continue to admire Edvard Munch, the painter of The Scream? Because, argues EH Gombrich in his canonical art-history, The Story of Art, Munch was one of the first modern artists to fully favour an individual’s sensory experience over academia’s painterly rules.

Munch’s most famous work might have been created in the mid-1890s, yet Gombrich covers this artist in chapter 27 of his book, Experimental Art: The First Half of the Twentieth Century. Munch is placed here, because he comes immediately after a quite distinct earlier generation: the Impressionists. A few years earlier, Monet, Manet and co had done away with certain art-school conventions - such as painting models in a studio, lit by a single light source - because they felt these techniques did not produce pictures that reflected the world as it truly was.

Munch followed this lead, favouring inner guidance over academic principle. Yet in attempting further innovations of the form, Munch and co “discovered that the simple demand that they should ‘paint what they see’ is self-contradictory,” Gombrich explains. “We can never neatly separate what we see from what we know.”

This is because our sensory perceptions aren’t wholly camera-like. We have all, albeit momentarily, made mistakes seeing. “We sometimes see a small object which is close to our eyes as if it were a big mountain on the horizon,” Gombrich writes by way of example, “or a fluttering paper as if it were a bird.”

Bearing this subjectivity in mind, how should an artist honestly capture the world alive with “sense impressions”? “If we look out of the window,” Gombrich says, “we see the view in a thousand different ways. Which one of them is our sense impression?”

“This, I think, is the difficulty which was dimly felt by the generation that wanted to follow and surpass the Impressionists and which ultimately led to the rejection of the whole Western tradition,” he goes on, “these artists of the twentieth century had to become inventors. To secure attention they had to strive for originality rather than for that mastery we admire in the great artists of the past.”

One, young, ambitious painter demonstrated a degree of originality above all others. “Among the first artists to explore these possibilities,” writes Gombrich, “was the Norwegian painter Edvard Munch.”

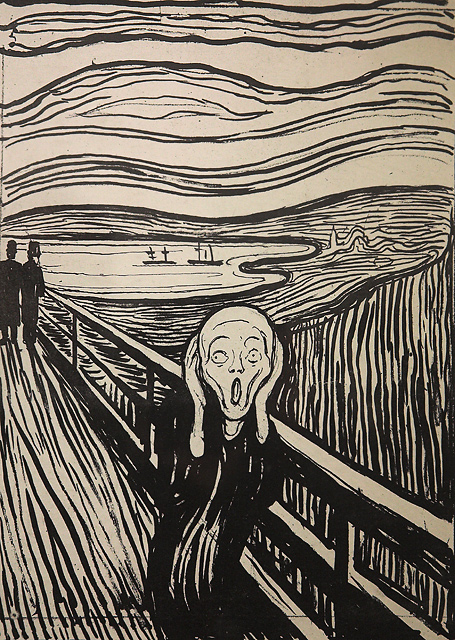

To demonstrate Munch’s superiority, Gombrich looks at just one image where the artist’s sense impressions triumph over simple figurative concern: the Scream.

“It aims at expressing how a sudden excitement transforms all our sense impressions,” Gombrich writes. “All the lines seem to lead towards the one focus of the print – the shouting head. It looks as if all the scenery shared in the anguish and excitement of that scream. The face of the shouting person is indeed distorted like that of a caricature. The staring eyes and hollow cheeks recall a death’s head. Something terrible must have happened, and the print is all the more disquieting because we shall never know what the scream meant.”

While the subject remains enigmatic, the example set for fellow artists was quite clear. Value sensory accuracy over draughtsmanship, and a whole range of novel possibilities, from Cubism, to Abstract Expressionism to Surrealism, come into view. Yet each of those are, for Gombrich, another story.

For a richer understanding of this artist, seek out a copy of our Munch monograph, and for a stronger sense of how he fits into the wider canon, buy a copy of The Story of Art here.