William Eggleston's blood red revelation

Discover how a photo machine changed Eggleston’s world view and encouraged him to favour extreme colours

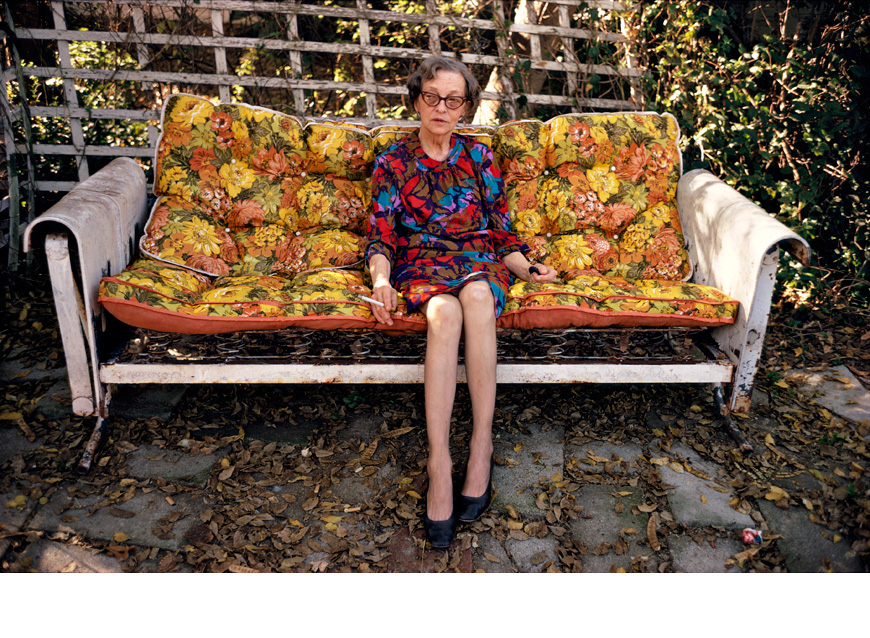

Today we regard the American photographer William Eggleston as a master of brilliant, bright colour photography, yet visitors to his exhibition at London’s National Portrait Gallery will see quite a few early black-and-white prints in among the display of 100 portraits.

What made him switch from monochrome to such bright pigments? Perhaps it was an encounter with a photo-processing machine.

“There is an anecdote about Eggleston in the mid-1960s, watching in the middle of the night as hundreds of colour snapshots were churned out of developing machines at one of the first industrial photofinishing laboratories,” writes Professor Mark Durden in our book Photography Today. “Such an experience marked a turning point in his photography, influencing his use of colour to depict ordinary subject matter drawn from his own private milieu.”

“The mundane world was transformed through Eggleston’s distinctive use of super-saturated colour, the result of the expensive dye-transfer printing process, which had previously mainly been used for commercial photography and magazine publication. The process meant, as Eggleston has said, ‘it doesn’t look at all like the scene, which in some cases is what you want’.”

“In relation to his photograph, Greenwood, Mississippi (1973) [top], showing a cross of white cables leading to the central lightbulb on a red ceiling in his friend’s guestroom, he noted, ‘When you look at the dye, it is like red blood that’s wet on the wall.’” Durden explains. “The colour also gives a distinct erotic association to the interior space, which is echoed by the detail of a poster showing diagrams of differing sexual positions. The poster’s depictions of interlocked bodies might even be seen as giving suggestive connotations to the cluster of little plugs drawing electricity from the cable that lights the bare bulb.”

For greater insight into both Eggleston’s work, and many other fine art photographers, order a copy of Photography Today here. And, if you're in London, don't forget to check out his exhibition at London’s National Portrait Gallery.