A Movement in a Moment: Humanist Photography

A look at the photographers who used their burgeoning skills to create a new sense of dignity

Walker Evans was, as we explain in The Photography Book “one of photography’s outstanding artists”. By the 1930s he was a prominent figure in the New York cultural scene; Ernest Hemingway and John Cheever numbered among his friends. So why, when he was at the peak of his maturity as an artist, did he take a job as a photographer within a small governmental programme? Perhaps the answer lies in the artistic power photographers once believed lay within their medium.

Humanist photography is a term used to describe a particular type of mid-century photojournalism that lies somewhere between the painterly, honourable concerns of realism and the high-minded hopefulness of modernism.

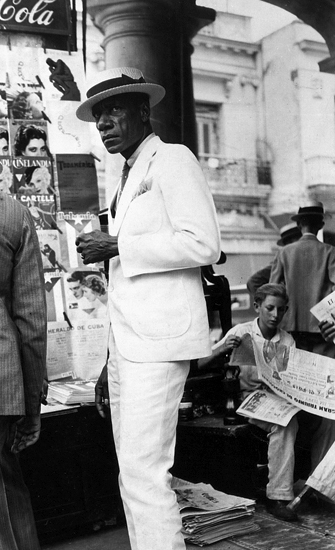

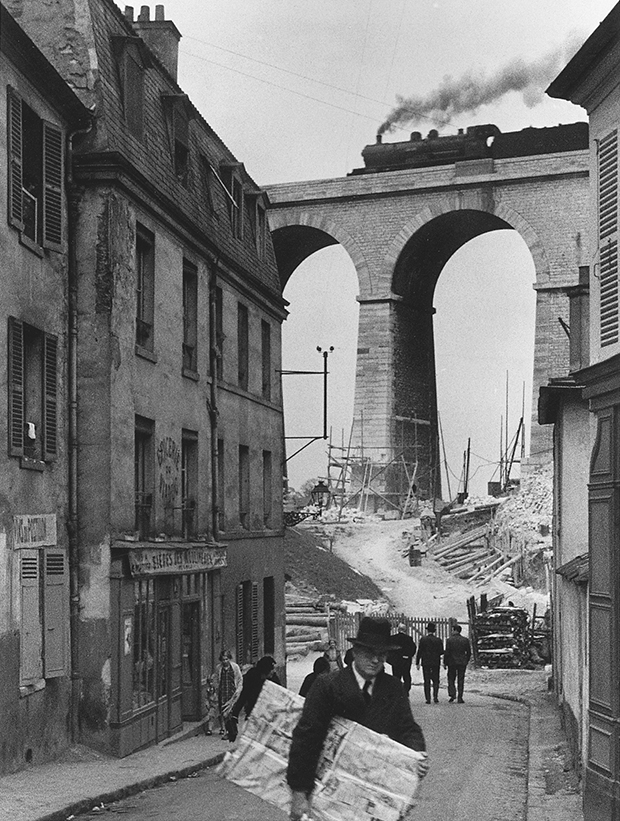

Early practitioners in Europe, such as André Kertész Willy Ronis and the Magnum co-founder Henri Cartier-Bresson, used newly developed Leica cameras in the 1920s and 30s – which removed the need for tripods or studio set-ups – to document the social foment on the avenues of the continent.

Mastering the technical aspects of photography, and free to roam within an increasingly open society, these photographers celebrated and ennobled the common man and the simple street scene.

Away from the horrors of the trenches and the strictures of pre-war society, humanist photographers saw that their new medium might not only find beautiful pictures in plain places and faces, but, in showing the nobility of the common man, they might also engender a new sense of compassion and mutual understanding.

In Paris, this lyrical style of reportage suited the hopeful ambitions of the interwar period, yet in America the movement also found fertile ground, thanks in part to the centre-left politics of the New Deal, and also European-born immigrants such as the photographer and curator Edward Steichen, whose hugely ambitious Family of Man exhibition of 1955 sought to assert mankind’s goodness and unity.

The work Walker Evans and co. undertook with the depression-era Farm Security Commission, shows humanist photography at its most expressive and didactic.

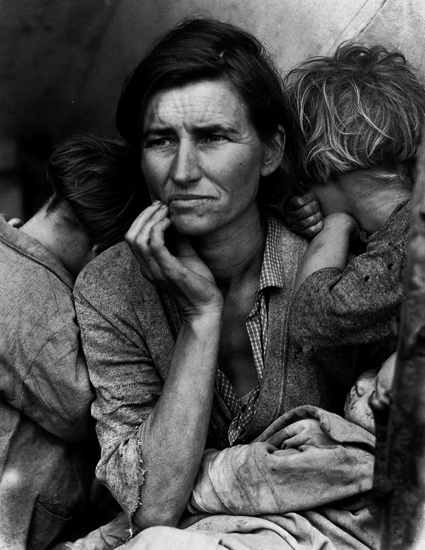

The small band of photographers attached the FSC, which included Dorothea Lange and Gordon Parks, formed part of a larger effort to improve the lives of poverty stricken rural folk. The FSA helped farmers buy land, and resettle them into more effective, larger agricultural projects. Evans and co were employed in part to document the poverty, but also to also engender empathy and sympathy in other Americans, who might otherwise not have cared about their fellow countrymen.

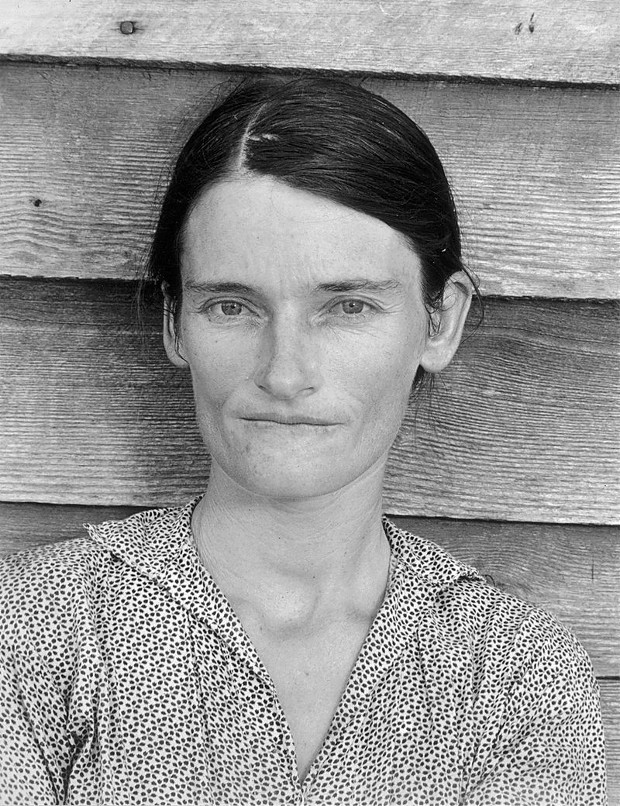

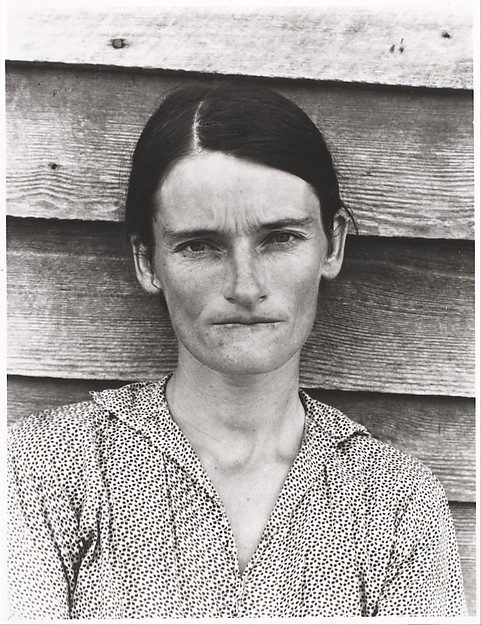

The scheme worked; Evans’ portrait of Allie Mae Burroughs, alongside other images such as Dorothea Lange’s migrant mother, remain masterpieces of human dignity as well as symbols of depression-era America.

So why did humanist photography decline in the later decades of the 20th century? Partly because of political changes; after Vietnam and Watergate that hopeful sense of human progression simply lessened. There were also artistic reasons too. As Mark Durden explains in Photography Today, “from the 1970s onwards, documentary faced a concerted effort to displace its importance. As photography was taken up and used by Conceptual artists, its documentary form was often subject to parody and critique.”

You only have to look at the US post-modern artist Sherrie Levine’s re-photographing of Walker Evans’ FSA photos for her 1981 series, entitled After Walker Evans, to understand Durden’s point.

Nevertheless, the humanist spirit does live on in many photographers, from Joel Meyerowitz’s beautiful street photography, to Stephen Shore’s Survivors in the Ukraine, wherein he captures the dignity of rural European holocaust survivors, through to the French photograffeur JR, whose monumental, pasted-up photos of today’s migrants and downtrodden women makes us care for people we might have otherwise overlooked.

For more on the history of photography get The Photography Book; for more on humanist photography's place in the contemporary sphere, get Photography Today;