My Body of Art - Hank Willis Thomas on Eadweard Muybridge's frozen movement photographs

The US contemporary artist admires Muybridge's pioneering work breaking down human movement

Would Eadweard Muybridge have been surprised to find himself in a book like Body of Art? Our important new title examines the beautiful and provocative ways artists have represented, scrutinized and utilized the body over centuries.

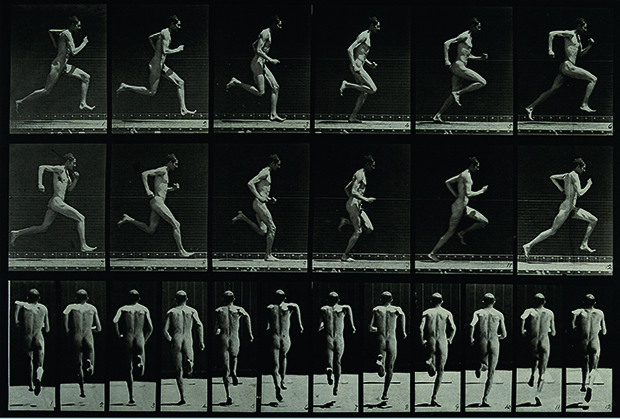

Muybridge's 19th century photographic sequences were shot with the assistance of the physiology, engineering and anatomy professors at the University of Pennsylvania, not the fine-art department. Yet, as the entry accompanying the photographer's famous Man Sprinting sequence explains, “although originally intended as a scientific study aid, the photographs of this anonymous runner have transcended their original context to become iconic images in the history of photography, and they represent an important step in the development of cinematography.”

Muybridge's work guided 20th century artists, including Marcel Duchamp and Francis Bacon, and it continues to exert a strong influence today. Hank Willis Thomas, the contemporary American fine-artist, admires Muybridge's pioneering ability to break movement into a series of seemingly static poses. In an interview over on Artspace, posted to promote our new book, Thomas says, “I think Muybridge’s studies of the body are some of the very first examples of someone bringing awareness to the way in which things that seem fluid are actually connected to a number of other things. Movements are always connected to a combination of gestures, and he was one of the first to show that using photography.”

Thomas trained as a photographer, and now also sculpts and produces installations. His art tends to focus on the themes of identity, history and popular culture, yet he appreciates the facility Muybridge's techniques passed on to us all, allowing us to reduce movements into a set of frames.

“I've always been interested in framing and context,” he tells Artspace's Dylan Kerr, “in thinking about how any and every historical moment can be retold by a split-second change in the moment of capture.”

“In some of my more recent sculptures, I’ve started taking images from photographs and freezing them, to turn them into sculptures. That's definitely a nod to Muybridge—I’m thinking about framing a moment and what that means, but also giving it a different perspective. When a photograph becomes a sculpture, all of a sudden you get to walk around it and interpret it in new ways.”

Look at Thomas's recent sculpture, Opportunity, and it's hard not to consider preceding and subsequent events surrounding a single successful sporting play.

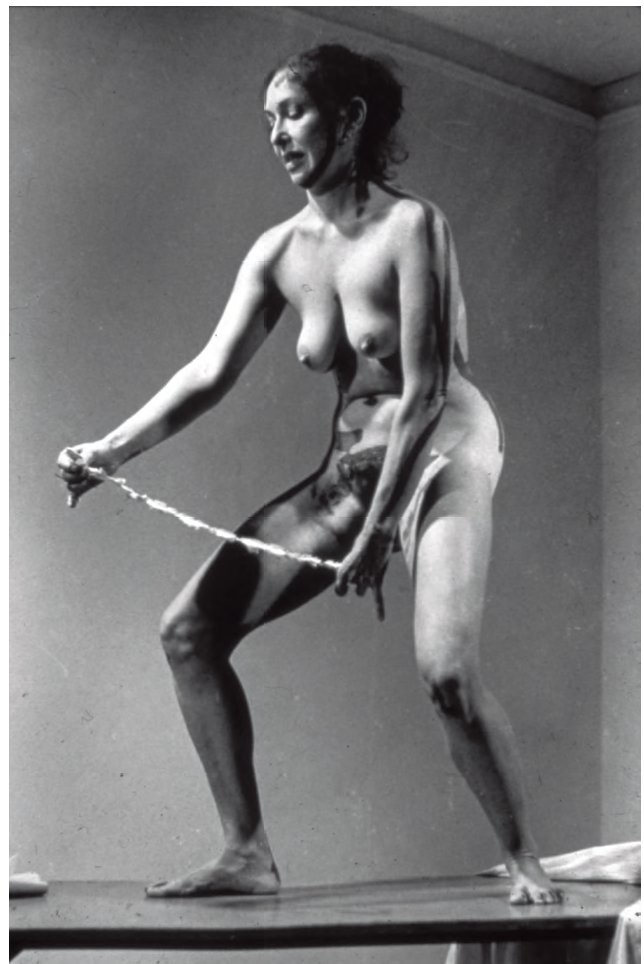

The detached, scientific quality of Muybridge's work stands in contrast to Carolee Schneemann's Interior Scroll performance – another piece Thomas singles out from Body of Art.

Here's how the book describes the performance: “Standing on top of a table and clad only in an apron, Carolee Schneemann ritualistically painted contour lines on her body and then read from her book Cézanne: She Was a Great Painter. At the conclusion of the work, Schneemann dropped her apron and pulled a thin scroll from her body that had been wound up and hidden in her vagina. Reading aloud from the scroll, she recounted her interaction with a sexist male film-maker who criticized her art for its ‘personal clutter, persistence of feelings… primitive techniques, painterly mess’. Interior Scroll, like so much feminist art of the 1970s, enacted the mantra ‘the personal is political’. When shared publicly, the description of insults lobbed by a misogynist, personal feelings of inadequacy and the intimacy of one’s body constituted an act of political critique.”

The performance might sound like uncomfortable viewing for all but the most committed gallery-goer back in 1975. Yet, as Thomas says, the work remains important today. “She was dealing with the psychological, the physiological, and the phenomenological,” he says, “with the truly visceral experience of being a woman in that period of time and the expectations that went with that.”

Watching Schneeman's work might not be as easy as leafing through Muybridge's shots, yet Thomas believes artists should, at times, strive for discomfort.

“I think Carolee Schneemann, Marina Abramovic, and Joel-Peter Witkin were some of the first artists that actually scared me,” he explains. “They scared me because they were artists who were dealing with blood and dealing with flesh. They frequently did things that I definitely wished would never happen to me and that I definitely also wished that I didn't have to watch happen to another person. That speaks to elements of human life and the human experience that are often avoided. It's really crucial for artists to deal with the things that most of us don't want to have to pay attention to, in order to remind us that when we get lulled into comfort we often stop living.”

These diverse sources of inspiration both point to the vital sides of bodily life that – due to brevity or discomfort – we skim over, and how art can alllow us to recover them.

For greater insight into the body’s role in contemporary art from the earliest works through to the present day, please do buy a copy of Body of Art here.