My Body of Art - Fantastic Man’s founders on the influence of works like Portrait of Ross in LA

Jop van Bennekom and Gert Jonkers consider the effect AIDS had on the way gay men’s bodies were portrayed

What happens if you dislike the way your body is depicted in art? Perhaps not your own, personal physique, but the overriding style of bodily form that prevails in your community? This might seem like an odd question, yet it’s one that the co-founders of the men’s magazines BUTT and Fantastic Man have addressed over the past fifteen years.

“AIDS took away a lot of the happiness from gay media,” says Fantastic Man’s co-founder and co-editor Gert Jonkers.

“Before AIDS, it was more outlaw-ish, more subcultural,” explains his fellow founder and editor Jop van Bennekom. “After AIDS, depictions of gay men were never vulnerable. It was all about being strong and clean and healthy.”

This lack of bodily honesty is addressed in works of art from the subsequent period, such as Felix Gonzalez-Torres' Untitled (Portrait of Ross in LA). This 175-pound pile of sweets, which appears in The Absent Body chapter of our new book, Body of Art, was first created by the artist in 1991 and matches the healthy body weight of his lover, Ross Laycock, who died from an AIDS-related illness in that year. Gallery goers could take a piece of candy or two away, slowly depleting the pile, just as the disease had withered Laycock's body.

"Gonzalez-Torres created this work at a time when the subject of AIDS was still taboo," Body of Art explains, "and, as a metaphor for Ross's failing body, the work implicates the viewers who have unwittingly participated in its demise."

While neither Gert nor Jop employed such high-concept conceits, when the pair began their artfully conceived gay fanzine, BUTT, first published in 2001, and their stylish men’s title, Fantastic Man, which celebrates its tenth anniversary this year, they looked back at an earlier pre-AIDS period of bodily photography, which saw sexual liberation combine with fine-art photographic styles to offer a sensual, happy images of homosexuality.

“I love Peter Hujar,” says Jonkers, leafing through Body of Art. “Someone once said that Hujar should have had the success Robert Mapplethorpe enjoyed. I mean, I still love Mapplethorpe, but there’s something quite hard and contrived about Mapplethorpe, whereas Hujar is so warm and sexy.”

It’s an apt comparison, as both Mapplethorpe and Hujar were shooting fine-art photographs of their lovers and friends in New York City, just before the AIDS epidemic hit.

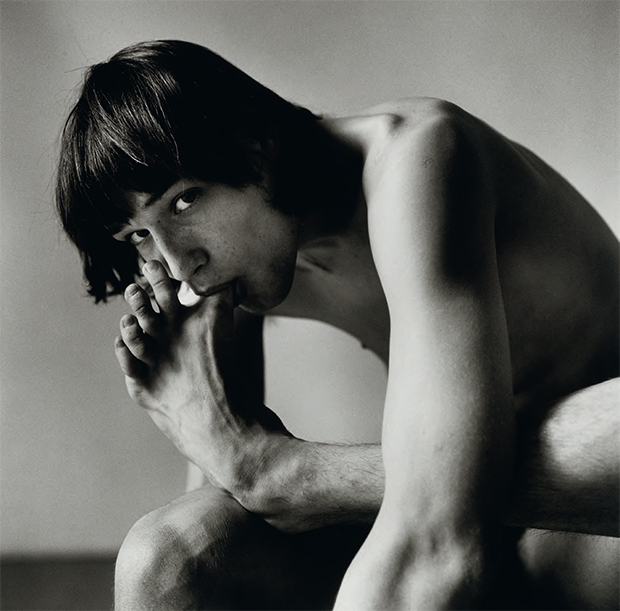

As we explain in our new book, Body of Art, “Peter Hujar (1934–87) made austere and exquisite black-and-white portraits of his friends, lovers and other denizens of New York’s Downtown demimonde during the 1970s and 80s. His classical style, which was both intimate and formal, bestowed gravitas on the drag queens, performance artists, musicians, artists, writers and film-makers who passed in front of his lens.

“Hujar inspired his subjects to reveal themselves, regardless of whether they were clothed or nude. This portrait of Daniel Schook emphasizes the tension between vulnerability and strength. Hujar captures an act – sucking a toe – that is both awkward and child-like yet also suggestive of autoeroticism. Schook gazes directly at the viewer through the floppy hair of a rock star, his artfully arranged head and limbs forming a square in the centre of the composition that conceals much of his nakedness.

“This photograph was made in the year in which the US Centers for Disease Control first reported on what would become the AIDS epidemic, which would ravage the community of which Hujar and his models were members. Hujar himself died of AIDS-related pneumonia six years later.”

Despite the changes AIDS wrought, Gert and Jop also found photographers to admire in the decades following Hujar’s death. In particular, Van Bennekom also drew influence from a more recent group of image makers, including Wolfgang Tillmans and Nan Goldin, who brought a point-and-shoot style of snapshot image making into the galleries.

“I remember seeing Wolfgang’s photographs in the mid-nineties. It really brought vulnerability out. His work was so real; it spoke so directly to you,” says Van Bennekom. “There was no boundary between his life and his art. It suited that period, with Nan Goldin and others; they all made the personal snapshot an important thing.”

Some of these personal photographs, such as Goldin’s One Month After Being Battered, make for uncomfortable viewing. “The camera lens acts as a mirror, “ we explain in Body of Art, “in which the artist reflects on past failures and on her resolve to overcome them.”

However, the honesty, and apparent ease with which these photographs were taken, inspired a generation of subsequent snappers, who saw that their life might also look good though a lens.

“I bought a camera and began shooting, and that style of snapshot, simple, flash-lit photography,” van Bennekom says. “It was all a big influence on my first magazine project." And, in so doing, Fantastic Man has become a clear influence on today’s image makers.

For more on Gert and Jop’s work, get a copy of Fantastic Man: Men of Great Style and Substance here; for more on the way our bodies have been portrayed in art, from the ice age up until the digital era, get a copy of Body of Art here.