War's effect on peace is examined in new Tate show

Tate Modern curator Shoair Mavlian talks us through the new exhibition Conflict, Time, Photography

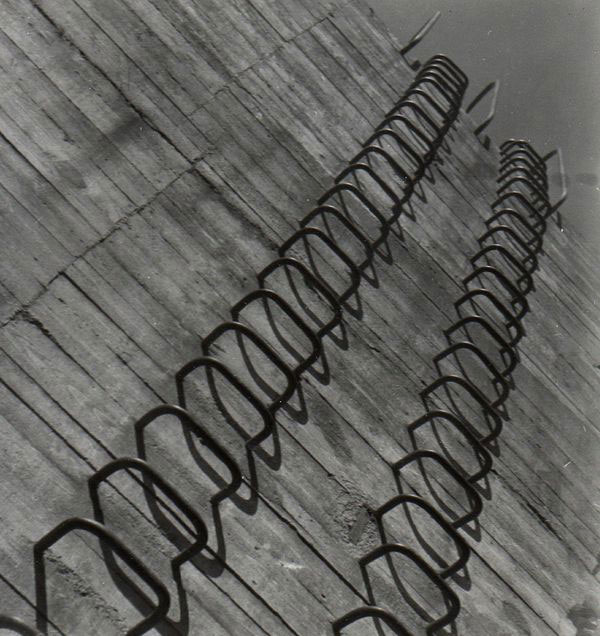

The Tate Modern’s new photography show focuses on war photography, yet it features very few images that you might find on a newspaper’s international pages. Staged to coincide with the centenary of the First World War, Conflict, Time, Photography looks at how artists have used the camera to reflect on moments of conflict, from the seconds after a bomb explodes, through to a full century after a truce has been declared.

Beginning with images taken in the very fog of war, the show is organized in a chronological manner, progressing on to images taken or re-appropriated hours, months, and years after the white flags have been raised. From Nicaraguan Revolution to the Balkans Conflict, Conflict, Time, Photography doesn’t so much capture the immediate destructive power of war, but rather its lasting legacy. We caught up with one of the show’s organizers, Shoair Mavlian, assistant curator at Tate Modern, who told us more.

Where did the organizing principle for Conflict, Time, Photography come from? It started with Slaughterhouse-Five, the novel by Kurt Vonnegut, which is about the traumas of the Second World War, and is told in a non-linear fashion. We realized very quickly that there was something important about the length of time it takes for artists to deal with images of the past.

Can you give me some examples? Well, the majority of the Japanese photo books about the Second World War appeared 15 to 20 years after that war ended. That seemed to be the period it took for artists do deal with the past. Time and trauma were closely connected.

It’s interesting you say ‘artist’, as we think of war photography as being a photojournalist’s medium. How many of these photographs were originally made as news images? Only the Don McCullin one [above], though there are a few artists who’ve used archives. Oliver Chanarin and Adam Broomberg have used the Belfast Expose Archive, which is an archive of both press images and photos taken by local amateur photographers.

It’s also interesting you mention photo books. We know Martin Parr, the photographer and author of our Photobook anthology, has quite a collection of Japanese photo books. Are any volumes from his collection on show here? Yes, Martin has lent us most of the Hiroshima books for this exhibition. We generally show a lot of photo books in our displays, but the photo books are particularly important with reference to Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

__You cover a wide variety of conflicts, from the Congo to Northern Ireland. It sounds like a terrible thing to say, but do certain conflicts make for more obviously compelling images? __ Not from our point of view. We really picked projects where an artist was specifically looking back at a particular event, that the artist feels the need to delve deeper into and re-contextualise.

War reporters are often placed under certain constraints. Are there images in here that demonstrate how those constraints have changed over time? Yes. Take the 1968 image by Don McCullin, showing a shell-shocked marine. McCullin himself says that this image couldn’t have been taken today. He was on the ground in Vietnam, with these soldiers, unsupervised. He talks about being airlifted out in a helicopter with them, and experiencing the trauma as the conflict was unfolding. Photographers don’t have that close proximity any more. There’s a distance that’s there with embedding, and with new technologies that allow you to photograph things from long distances.

What sort of material did you consider, but eventually choose not to show here? We made an early decision not to include any video or film. It was a photography show, and we could, of course, have done a whole exhibition of video and film.

You’ve included Stephen Shore’s Ukraine series, where Shore photographed in and around the homes of Holocaust survivors now settled in Ukraine. What did you like about that series? In a way it’s like American Surfaces, as he shoots these wonderful images of people and the surrounding environment. The project itself is huge (and will become a Phaidon book in the new year). We’ve tried to be quite specific, showing just a variety of different people that he was in contact with. For Stephen it was really important to keep the images grouped together, so we’ve hung the shots in clusters, so the people’s effects are next to images of their local surroundings.

Conflict, Time, Photography runs until 15 March 2015. For more on Stephen Shore go here; for greater insight into Parr's photo books take a look at our extensive range of book featuring and compiled by Martin Parr; also, for great conflict photography, consider our James Nachtwey book Inferno, our Robert Capa book and our VII Agency book, Questions Without Answers.