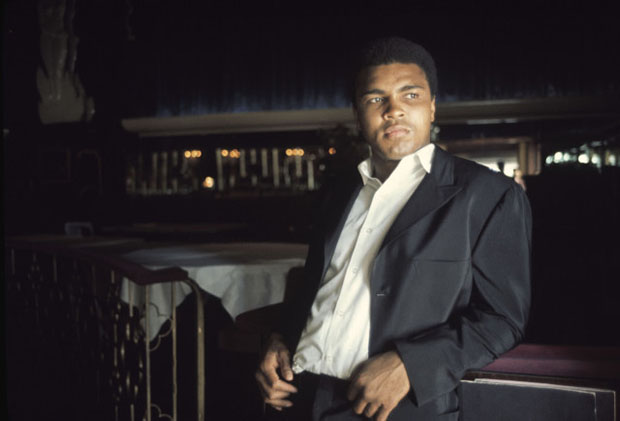

Danny Lyon's poignant memories of Muhammad Ali

'He was our king, our royalty, we will never have another like him. Goodbye champ - see you on the other side!'

The veteran photographer Danny Lyon has spent much of his career documenting the lives of outcasts, from outlaw bikers, to civil-rights protestors to Texan convicts. However, he also managed to photograph one of the most celebrated individuals of the 20th century: the boxer Muhammad Ali.

Following Ali’s death a few days ago, Lyon took a break from preparing for his huge Whitney retrospective, which opens 17 June, to look back on that 1970 shoot, and the way his subject conducted himself with enormous grace and dignity.

“The London Sunday Times asked Magnum if I could go photograph Ali who was in training in Miami,” recalls the photographer. “I didn’t do jobs and was not particularly interested in boxing or sports. I wanted to say “no” when my first wife Stephanie, who did like sports said “What? Are you crazy?” And so I went.”

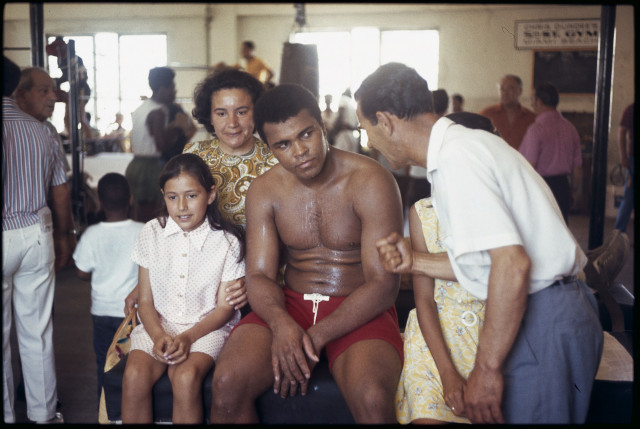

Lyon managed to spend three days pretty much alone with Ali in 1970, as Ali prepared to return to professional boxing, having been stripped of his license to fight in 1966 for refusing to be drafted into the US Army.

“He had gotten up early to run through a park and golf course in front of a Cadillac driven by [Ali’s longstanding trainer] Bundini Brown, running for miles before the heat got intolerable,” says Lyon. “One of my pictures shows Ali in the parking lot of his hotel, lifting his, shirt, sweat pouring off his chest like rain.”

The photographer believes he may have been picked for this commission because he was roughly the same age as Ali, and had played a significant part in the civil-rights movement. Certainly, the pair struck up a rapport.

“You would think this man, this world champion, this world-famous man would be a little distant. He was a great celebrity and you would think he would have some armor around him so when he encountered the public he would not have to suffer fools, but he had none. Ali was one of the nicest, most unassuming persons I’ve ever known. I could scarcely believe it. He suffered from the endless vilification by the press for becoming a Muslim and then after becoming the champion of the world, to change his name from Clay to Ali, this public disdain was seemingly joined by nearly everyone. Yet through it all he had managed to retain a brilliant child within himself.”

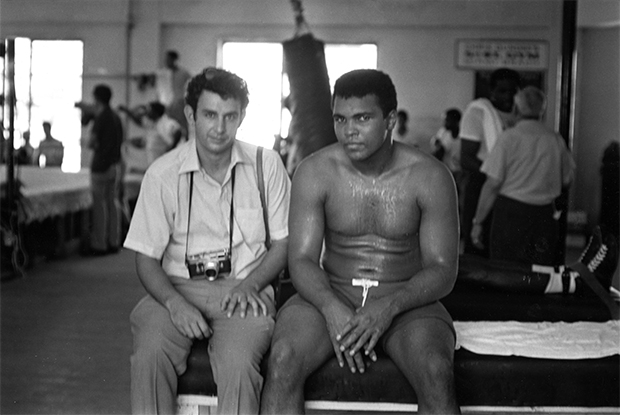

Indeed, the boxer’s incredible empathy and allure extended to all those around him. “We arrived so early at a restaurant the place was closed, “ Lyon recalls, “but when the waiter peeking out the door saw who it was, he let us in. Ali ordered steak and peas, I think he was on a diet for the fight, and during the meal I said what I had wanted to say to him.

“'I really admire you for what you did,' I said. 'I really admire that you said "no” to money, that you suffered all that because you were against the war.' I felt small before him and I was. His arm was as large around as my thigh. To me he was a moral giant. So it wasn’t easy for me to say anything to him, but I wanted to say that, to sort of thank him. And when I did, this was his response. “What I did was easy. Because I am famous, “ he said. “You know who I admire? I admire all those Black Muslim men locked up in prison that are being punished and no one ever heard of them. That’s who I admire.”

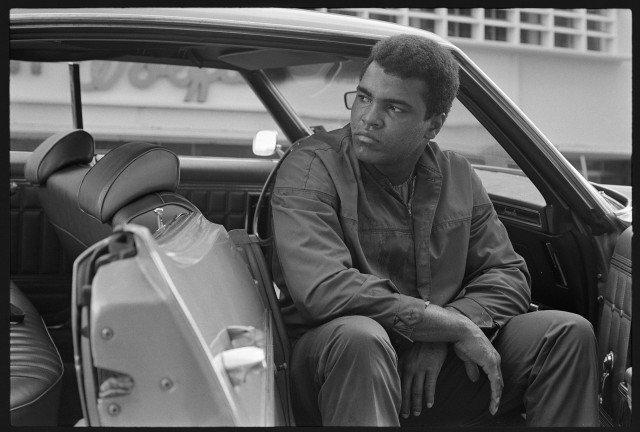

“Later we walked to a deserted beach near the edge of the strip. He was like a little kid. Going to a film, we were seated in the back of the car when he started speaking in poetry. He was going to knock Joe Frazier into the stratosphere. The launching of the first black satellite he said. He spoke in rhymed couplets. At the movie he ignored the line of mostly white people waiting to get in and picking up a red cord blocking the staircase he sat down on the steps to rest. When a young usher came over and bending down said, “I’m sorry sir you can’t sit there”, Ali looked up and said, “Yeah, and who is going to make me move?” It was funny, and he knew it. He asked me not to make pictures of him at the theatere because Muslims weren’t supposed to go to movies; then told me that watching the film, a western, was funny because he knew all the actors.

“We had gone to a beach because I wanted to make a picture there, and when we walked back up to the street, a long empty avenue, he saw a city bus approaching. He turned to me and said, “Watch this.” It was like he was putting on a show, for me. The bus came to the curb about twenty-five feet from where Ali was standing, when an excited passenger noticed him and came over to shake his hand. Then everyone on the bus got off, including the driver. They all wanted to see him, to touch him, it was like being with a king.” Lyon goes on, “He was our king, our royalty, and we will never have another like him. Goodbye champ. Hope to see you on the other side.”

For further great photographs from this period and many others order a copy of Danny Lyon’s book, The Seventh Dog, here, and check out the Whitney show here.