'He saw hammers and sickles when he went to Italy in the 70s' - Factory studio boss Vincent Fremont on Andy Warhol

How Andy's Skull series and Hammer and Sickle images were inspired by the extreme politics of 1970s Europe

Andy Warhol understood his times like no other artist, and included symbols in his work that very much captured the spirit of the age.

“He was always trying to find something that already had currency in the culture,” said Donna De Salvo, Chief Curator at the Whitney Museum, at the public talk, Andy Warhol: A Conversation, held at Phillips auction house, New York last Thursday.

Often those images came from commercial sources, such as advertising or the movies. However, Warhol also reached outside western capitalism when producing images such as his Chairman Mao series, or his Hammer and Sickle paintings.

Vincent Fremont, who worked with Warhol from 1969 until the artist’s death in 1987, recalled how a trip to Italy brought Warhol face to face with Communist iconography.

“He saw hammer and sickles when he went to Italy in the Seventies,” Fremont told his fellow panelists De Salvo, art critic Blake Gopnik and Phillips’s own Senior Advisor Arnold Lehman, in front of a specially invited audience.

Warhol visited Italy on a number of occasions during the Years of Lead (named after an era in Italy characterised by left and right-wing political terrorism involving bombings and assassinations).

Warhol’s response was to work the Communist symbol – seen graffitied on walls across the country – into a series of works, and also produce an accompanying set of Skull paintings, referencing, he later said, the death’s head insignias of fascism.

Unsurprisingly, the Italian art world was a little unwilling to show such politically contentious material.

“It was such a volatile time in the seventies with the Red Brigades that the galleries declined to show the show,” Fremont recalled; in the end Leo Castelli put the Hammer and Sickle works on show, in New York in 1976.

However, while the politics inherent in those images may be less evident today, Fremont contends that the works’ power remains undiminished.

“It’s still relevant,” he said, “because the image is so impactful, still controversial.”

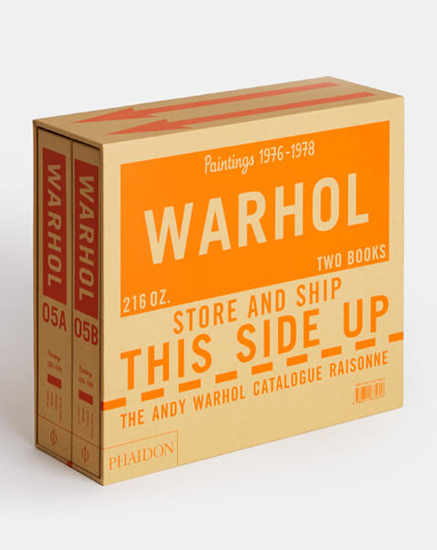

For a better grasp on Warhol’s process and output, order a copy of our magisterial overview, Andy Warhol Giant Size, and for the latest addition to our work-by-work examination of his career, order The Andy Warhol Catalogue Raisonné, Paintings 1976-1978 - Volume 5.