Pawson Projects: Product Design

How do you express the monastic life in a steak knife, or a geological age in an oil lamp? Well, take a look...

In our new book, John Pawson: Anatomy of Minimum the writer Alison Morris quotes the Italian architect Ernesto Rogers who once said if you “examine a spoon carefully you can understand enough about the society that made it to visualize how they would design a city.”

John Pawson hasn’t quite taken on urban planning just yet, however the world-renowned British architect has drilled down, designing the smallest of objects, which he regards as an extension of his architectural practice.

Indeed, many of his products have arisen from those building projects. “In the last couple of years the rigour of the Home Farm project has brought into sharp focus the need for objects in even the most pared-back of environments,” writes Morris, “at the same time as it has highlighted the importance of the right objects.”

Similarly, Pawson’s tableware collection for the Belgian company When Objects Work “began with the idea of equipping a refectory with a set of implements and vessels appropriate to the functional and aesthetic needs of a monastic community,” explains Morris in our new book, and so is informed by the Cistercian abbey Pawson had previously designed in the Czech Republic.

Meanwhile, the Sleeve Light, a simple pendant light fitting formed from two concentric hand-blown glass cylinders, was made for the Venetian glass company, WonderGlass, but proved to be a good fit for Life House, the Welsh holiday home Pawson designed for Alain de Botton’s Living Architecture.

Pawson’s Cast Bowl (top), explores the physical limits of cast ceramics, pushing the form to its breaking point. “Its diameter and profile are achieved by using a specially modelled open cast setter that prevents sagging and warping during firing,” explains Morris.

Meanwhile, the architect’s simple Holocene oil lamp, fashioned from steel and aluminium, is made to simply reflect and amplify a flame, yet its name – the Holocene being our current geological epoch – reminds us that Pawson’s seemingly timeless works are, in fact, made by one man at a specific point in time.

And perhaps that sense of space and time are a little more important than any of these products' more easily described design features. “For Pawson, it is consistently the case that the impact of what you are making on how you experience space, form and atmosphere is more significant than the object itself,” writes Morris. “When you change how and what you see and feel, there is scope to change what you know and what you value.”

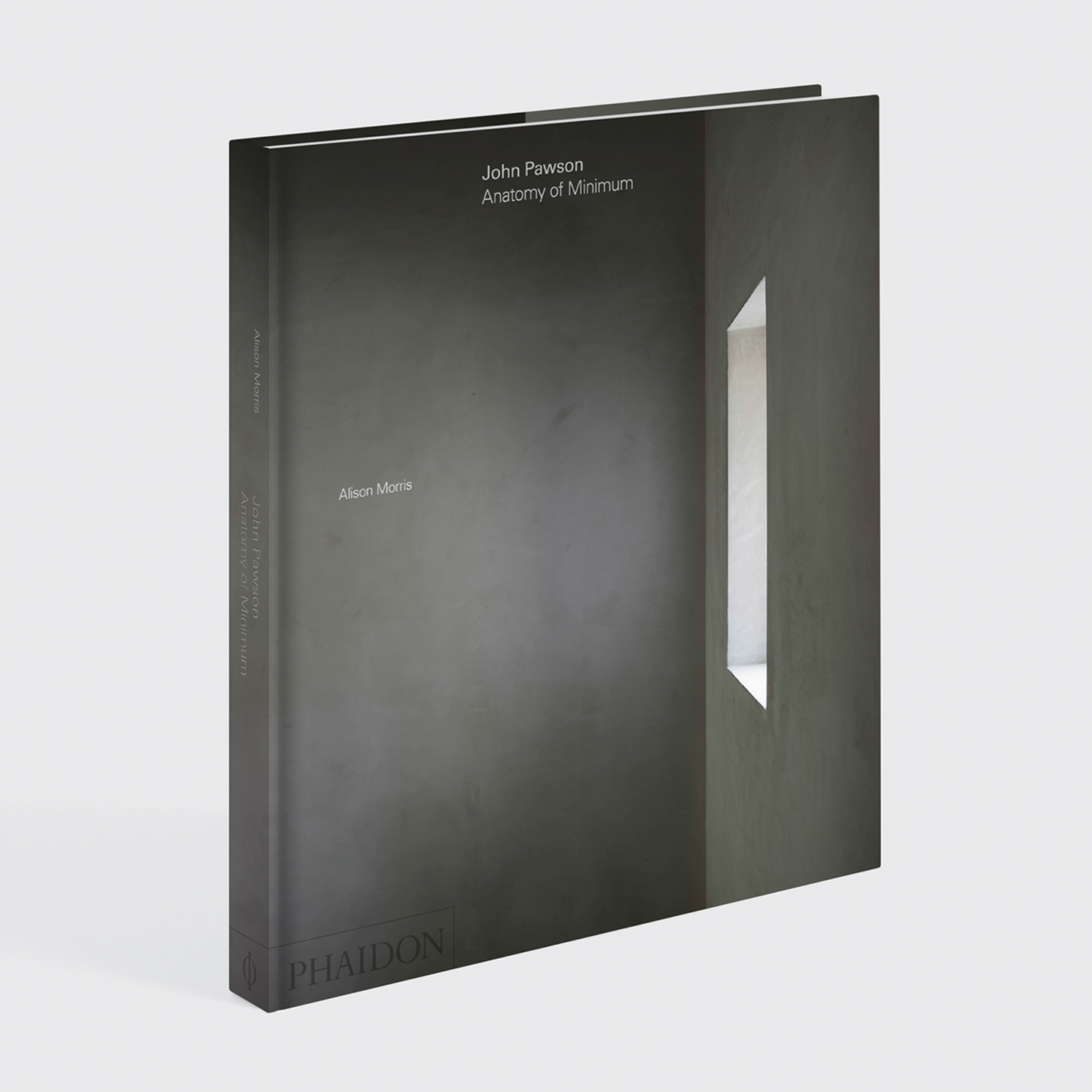

To change your knowledge and values a little, order a copy of John Pawson: Anatomy of Minimum here. The monograph, the latest in Phaidon's documentation of Pawson's stellar career, hones in on the essential details that mark his distinctive architectural and aesthetic style.

The book groups a selection of his recent works into domestic projects, including his own house in rural England; extended sacred spaces; and repurposed structures, such as London's Design Museum. Throughout its pages, this book explores Pawson's unique approach to proportion and light and his precise language of windows, doors, and walls. You can buy John Pawson: Anatomy of Minimum here.