Remembering Keith Haring

On the anniversary of his death, Annie Leibovitz and our Art & Queer Culture authors recall the 80s pop-art star

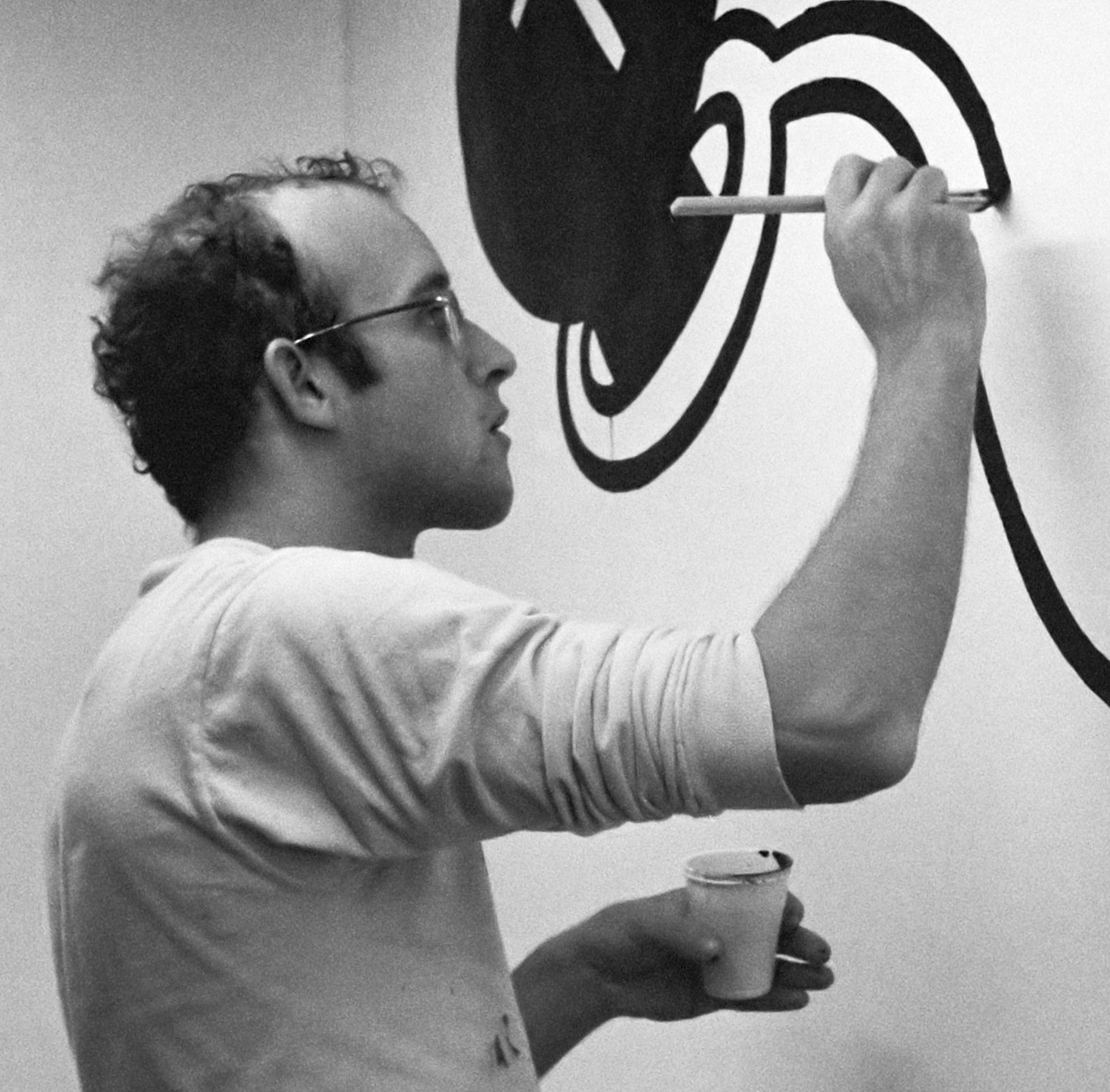

When Annie Leibovitz came to photograph Keith Haring in 1986, he was the closest thing the art world had to a pop star. Haring, who died on this day (16 February) in 1990, was well known within New York’s club and music scene; he hung out with Madonna, worked with Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood, and had befriended Andy Warhol. In fact, it was an old Warhol commission that inspired Leibovitz’s shoot.

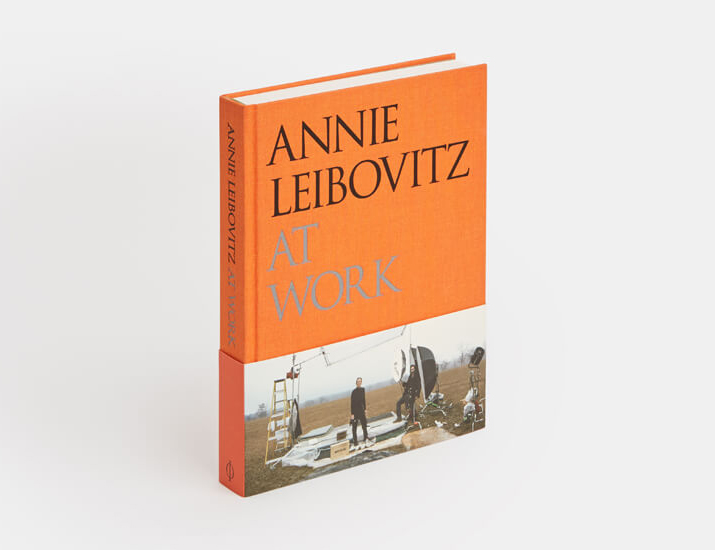

“Keith and I talked on the phone and I asked him if he had ever painted himself,” she explains in her book, Annie Leibovitz at Work. “He said no, although a couple of years earlier Andy Warhol had arranged for him to paint Grace Jones and to have Robert Mapplethorpe photograph her when Keith was finished.

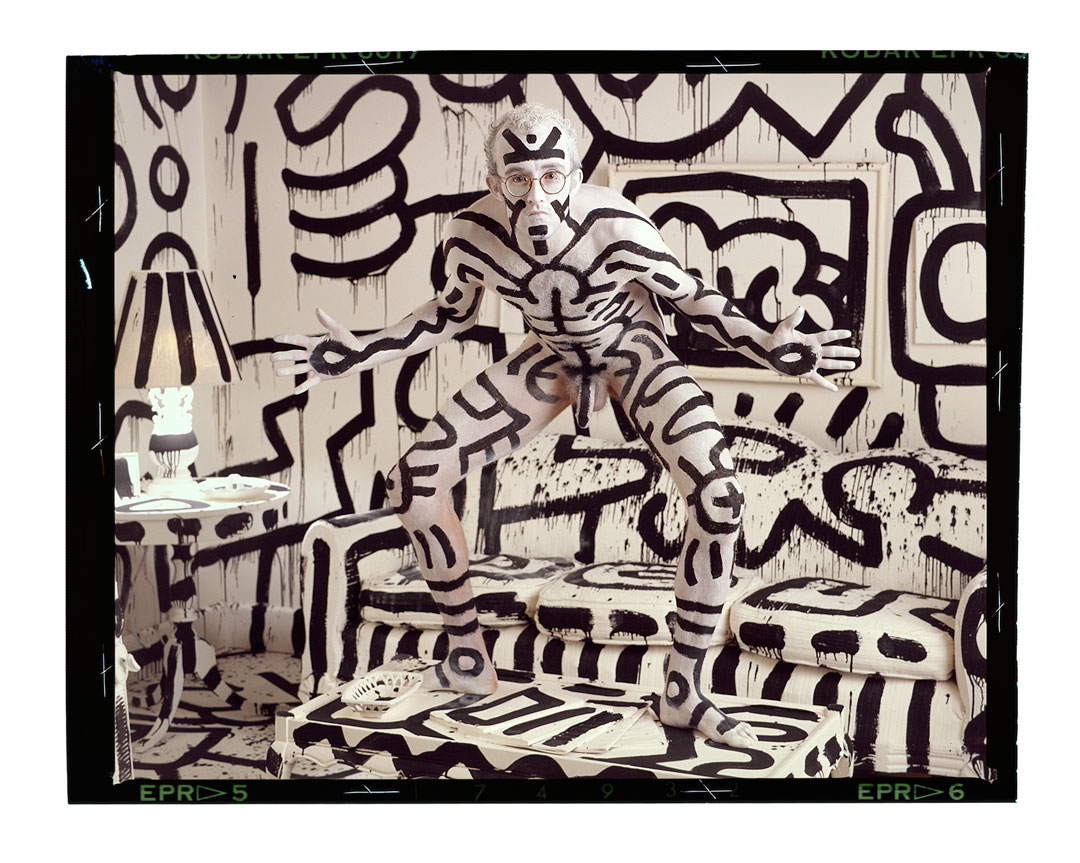

“We decided that he would paint his torso for me. We shot it in the studio, on a set constructed to look like someone’s living room, then painted it white. When Keith arrived he painted the room with black lines in less than forty-five minutes. Then he painted his upper body in about five minutes. When he came out of the dressing room he was wearing white painters’ pants, but it just seemed obvious to both of us at that point that he should paint the rest of him.

“It’s hard to paint yourself. Keith did only the front. I loved the way he painted his penis. It was so witty, with an elongated line. The pictures took only a few minutes, and when we finished, Keith didn’t want to stop. He said he felt dressed and wanted to go out. I suggested we go to Times Square, which was a few blocks away. This was 1986, and it was still pretty rough. The peep shows and the porn houses were still there. In the car on the way over I told my assistants that we were going to have to work fast because we’d probably get arrested.

“I photographed Keith in back of the statue of George M. Cohan in Duffy Square and in front of a bank. It was a cold winter night and this painted, naked guy was walking around, and nobody, including a couple of policemen who were there, paid any attention to us.”

That laissez-faire urban environment not only helped with Haring’s shoot, it had actually helped him develop his art. As Catherine Lord explains in our newly updated book, Art & Queer Culture, Haring was lucky to have developed as an artist in a forgiving, permissive city.

“For a New York minute, between punk and the East Village, the scene was one of surprising generosity,” writes Lord. “Xerox flyers wheat-pasted onto hoardings, like Jenny Holzer’s Truisms, rendered hollow the authority of public signage. David Wojnarowicz’s spray-painted graffiti on the Chelsea piers occupied a heavily trafficked sex site almost invisible to a purportedly straight world. The sprawling 1980 ‘Times Square Show’ tacked works on paper, for all practical purposes anonymous, upon the walls of a disused building. In the subways, Keith Haring waylaid the foundations of commerce, taking as a drawing surface the black paper panels awaiting advertising posters.”

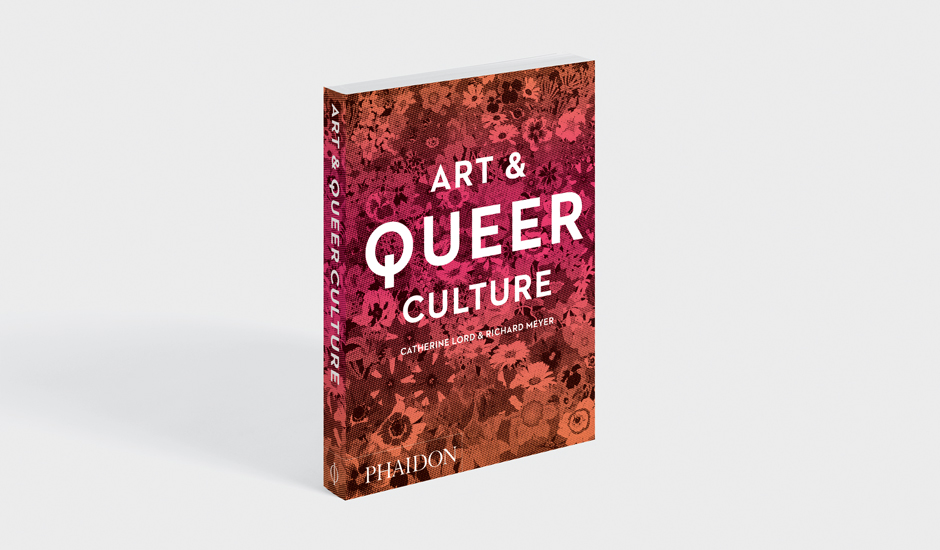

And though Haring found fame and proper gallery recognition, he never entirely abandoned those permissive spaces. Art & Queer Culture focusses on his mural, Once Upon a Time, painted in the bathroom of a NYC homosexual community centre.

“To commemorate the twentieth anniversary of the Stonewall riots in 1989, Haring created an orgiastic mural for the men’s room of the Lesbian and Gay Community Services Center,” explains our book. “A popular attraction to the Center, the men’s room has since been repurposed as a meeting room for use by community members of all genders.”

Haring completed the painting the year before his death, and the year after his AIDS diagnosis, and while the title clearly refers to the liberation Stonewall brought, it’s hard not to read it as a reminder of a fabled, more innocent time, back when public nudity wasn’t anything to remark on, and love was a bit more free.

For more on Haring’s place in art and queer culture, get Art & Queer Culture. For more on Annie Leibovitz’s Haring shoot and plenty else besides order Annie Leibovitz at Work.