The race to shoot the Moon

Mark Holborn's new book describes the lengths 19th century star gazers went to in order to depict the Moon

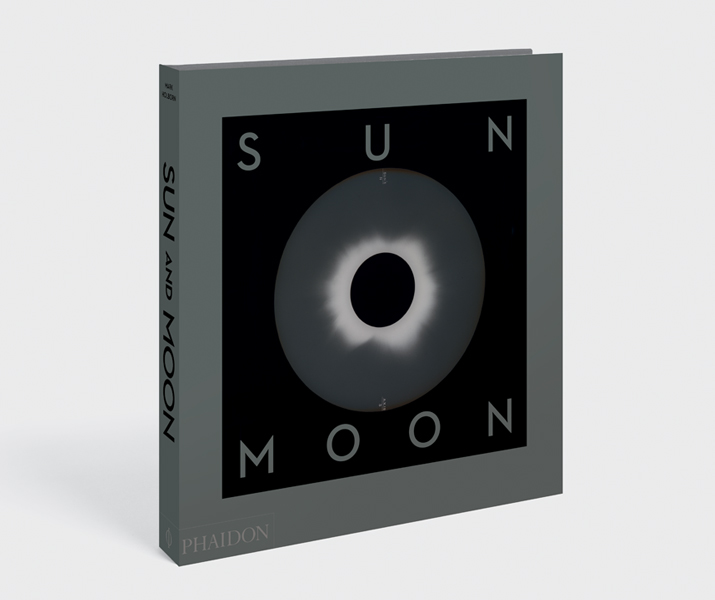

Stargazing and photography were almost made for one another. “The language of blackness is in accord with the visual references of the photographic plate,” writes Mark Holborn in his new book Sun and Moon: A Story of Astronomy, Photography and Cartography, “Along with human portraiture, the first subjects for daguerreotypes in the nineteenth century were studies of the Sun and the Moon.”

Yet shooting a picture of these celestial bodies wasn’t as straightforward as capturing a human likeness, and our earthly attempts to gain a good view of these celestial bodies could be viewed as a kind of 19th century space race.

The competition began with the widespread use of photography. “In 1839, John Draper, an English chemist originally from Lancashire, who had settled in Virginia then studied medicine in Philadelphia, took up a professorship at New York University,” writes Holborn.

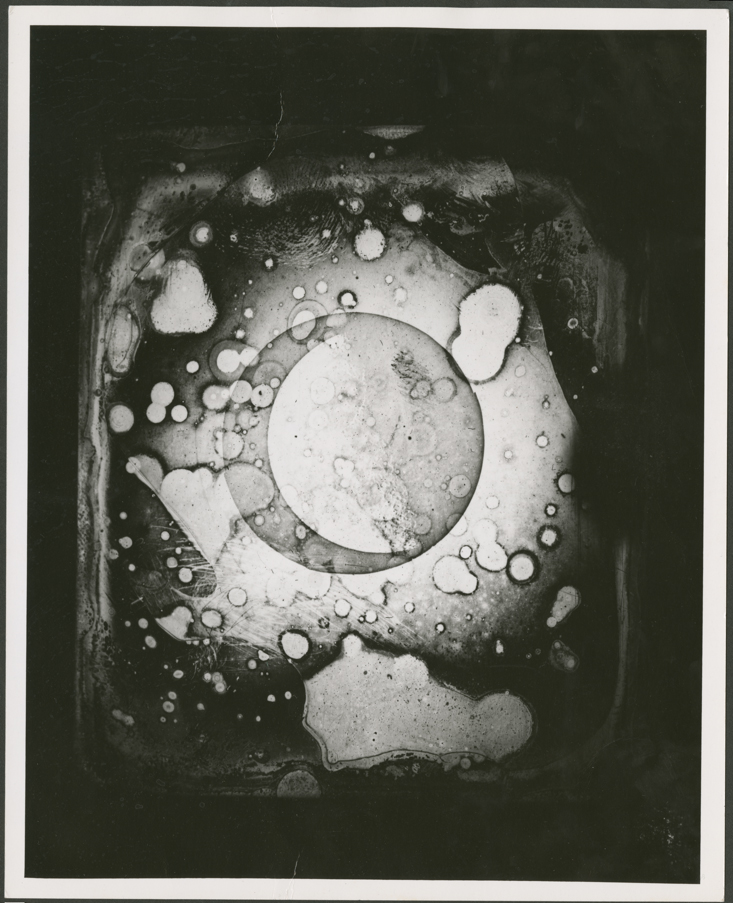

That same year the Frenchman Louis Daguerre invented and introduced the world to the daguerreotype the first widely available photographic process. “Excited by the announcement of Daguerre’s process, Draper began to produce his own daguerreotypes,” writes Holborn. “The process required such a long exposure that only the brightest objects could be recorded. He found that a portrait of a sitter on a bright day required an exposure of five to seven minutes. An astronomical photograph presented the technical difficulties involved in rotating the telescope at a constant speed over the period of the exposure and in the rigidity of the tube. The longer the telescope, the greater the possibility of movement in the tube, causing a shift in focus. In March 1840, Draper presented to the Lyceum of Natural History of New York a daguerreotype of the Moon made from the rooftop of the university observatory. The image was about an inch wide and was produced following an exposure of twenty minutes.”

Despite its historical importance the image, which appears in Sun and Moon, isn’t especially detailed or lifelike. However, others realised that Draper’s image could be improved if, rather than attempt to shoot the Moon, they pointed their camera at a brighter point in the sky.

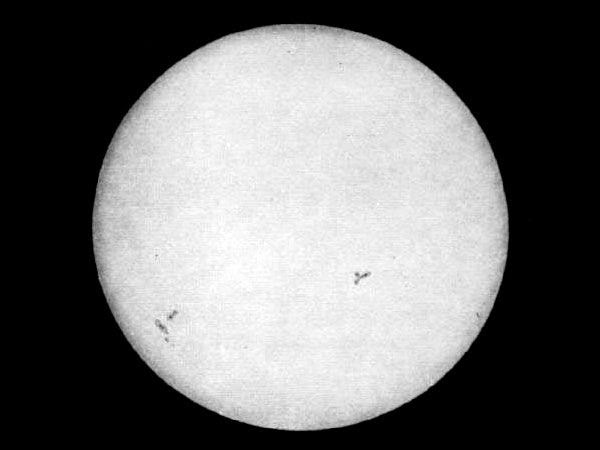

“Five years after Draper’s success, the French physicists Léon Foucault and Hippolyte-Louis Fizeau created a daguerreotype of the Sun some 3 1/2 inches (around 9 cm) wide with a dramatically shorter exposure time given the intensity of the subject,” writes Holborn.

The French duo’s success didn’t just lie in their choice of subject. “Fizeau had attended lectures by Daguerre and was deeply engaged by what he heard. He realized by heightening the sensitivity of the plate, he could reduce the exposure. Instead of minutes, he was dealing with seconds.”

Across the Atlantic, others were tinkering with both the physics and chemistry of telescopic photography to better the chances of a descent Moon shot. Holborn describes the work of William Cranch Bond, a skilled clock-maker, astronomer, and Astronomical Observer at Harvard. He struck up a fruitful partnership with John Adams Whipple, an American inventor and photographer.

“Bond and Whipple collaborated on photographing the Moon and from 1849 produced daguerreotypes of the highest quality,” Holborn explains. “The Harvard refracting telescope was fitted with a clockwork mechanism that enabled them to track the Moon and reduce the softening blur of planetary motion. The excellence of Whipple’s work was reinforced when one of his daguerreotypes of the Moon was awarded a gold medal at the Great Exhibition held at the Crystal Palace in London in 1851.”

Yet, having pushed lunar photography to its limits, others tried to get around the medium’s restrictions in other ways. Holborn reproduces a strikingly lifelike image of a lunar crater made by the English polymath, John Herschel. Taken in 1842, just three years after Daguerre’s invention, and seven years before Bond and Whipple’s winning photographs, Herschel’s image appears to best them all, with an apparently detailed, lifelike, up-close depiction of the Moon’s surface.

However, Herschel wasn’t actually photographing the Moon itself, “but pictures of plaster models of the lunar surface, no doubt intended to demonstrate the clarity of the image he could achieve, rather than to suggest any original observation,” writes Holborn.

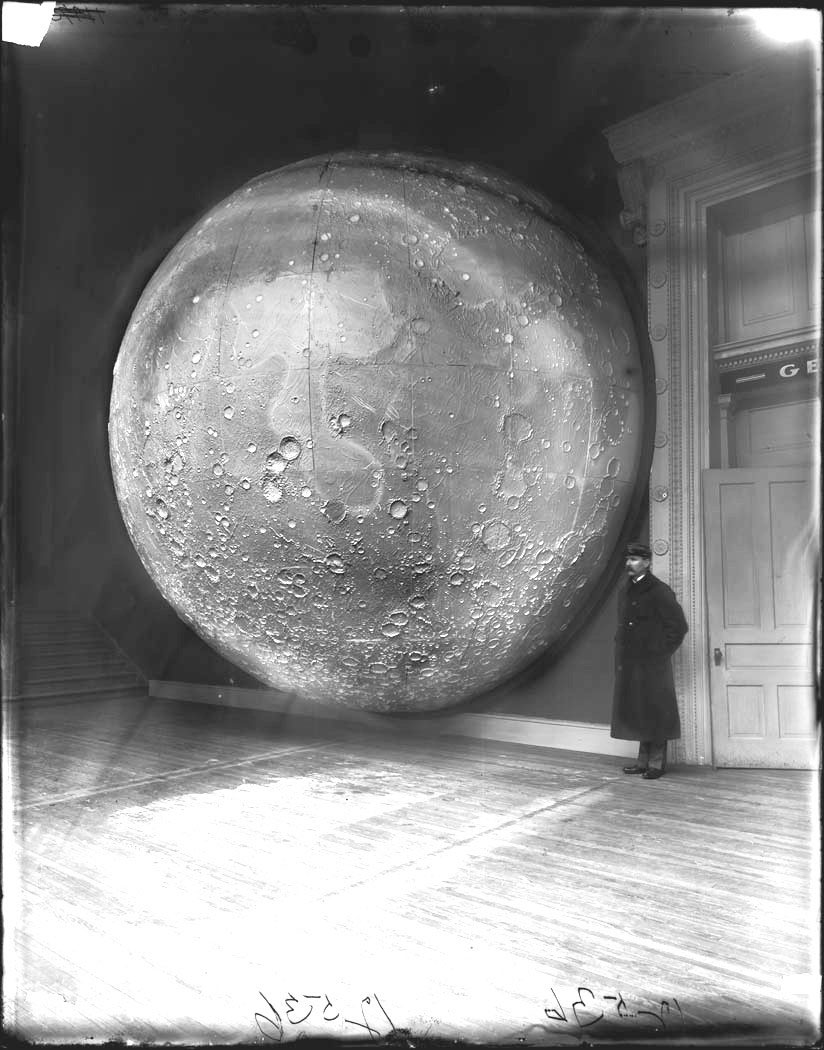

And Herschel wasn’t alone in this curious work-around. Others saw detailed plaster modeling as a way to bring the Moon into view. Holborn also tells the tale of the Johann F. J. Schmidt, “an astronomer from Hamburg and Director of the Athens Observatory in the mid-nineteenth century, was fixated on selenography [the study of the Moon’s surface].”

Towards the end of his life, Schmidt created a massive model of the Moon. “This colossal wood and plaster model on a metal frame comprised of 116 sections,” writes Holborn. “The dimensions of this Moon corresponded to Schmidt’s devotion. The result shifted lunar contemplation from the sublime to the absurd and the surreal.”

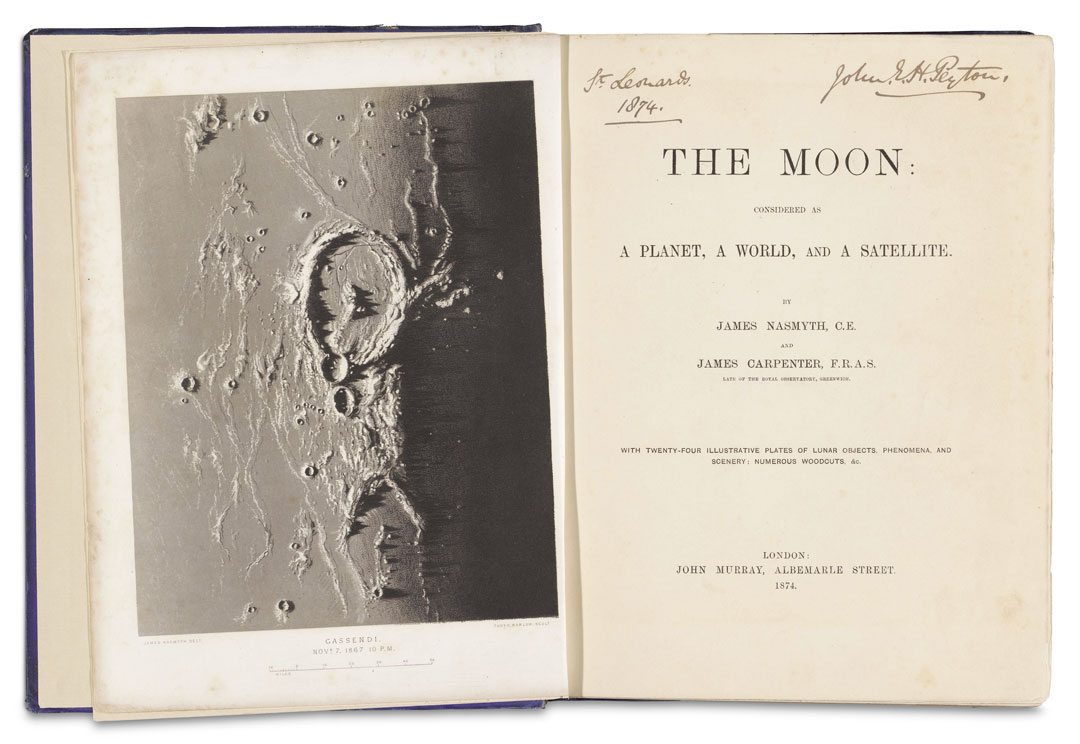

For a more considered trip to the Moon, 19th century astronomers might have turned to the Scottish engineer James Nasmyth who, having made his fortune during the industrial revolution, devoted himself to the Moon, publishing, in 1874, The Moon: Considered as a Planet, a World, and a Satellite, with James Carpenter from the Royal Observatory at Greenwich.

“The book was the result of many years of observation,” writes Holborn. “This lunar monograph contained twenty-four photographic plates of the Moon, all derived from the painstaking transference of sketches of sections of the Moon’s surface into accurate plaster relief and photographed with the appropriate sunlight to heighten the sense of topography.”

Nasmyth didn’t only attempt to depict the Moon; he also tried, via the book’s text, to transport his readers to the surface. “Towards the end of his book, he addressed the issue of possible life on the Moon, which he dismissed,” writes Holborn, “and went further to describe vividly what he elegantly calls a ‘sojourn’ on it, with the insight of one who has looked past the detail of a lunar landscape to what the experience of traversing that landscape would entail.

“One of his more profound suggestions, exhibiting a degree of prophetic insight, was a full description of the Earth as seen from the Moon during the course of a terrestrial day and night. The exploration of lunar terrain as an actuality – rather than through an informed but imaginative projection – by the astronauts of the Apollo missions almost a hundred years later may well have confirmed Nasmyth’s description. But among the most powerful observations shared by the astronauts was the fact that space travel and the eventual landing on the Moon enabled the human gaze to be directed back at the planet of origin – the view of the Earth from Apollo 11 was as memorable as that of the Moon to which the astronauts were travelling. In his writings, Nasmyth presented the Earth with comparable awe.”

Viewers would have to wait a little under a century for a descent photographic depiction of the Earth from the Moon; yet, with a little 19th century ingenuity, and educated leap of faith, this British amateur was able to deliver this view from space a little ahead of time.

For more on the earthly story behind heavenly image making, order a copy of Sun and Moon here.