A Movement in a Moment: Institutional Critique

Discover how artists developed a new mode of expression - by criticising public art institutions

During the summer and early autumn of 1970, a German artist took a pop at one of the most powerful men in America.

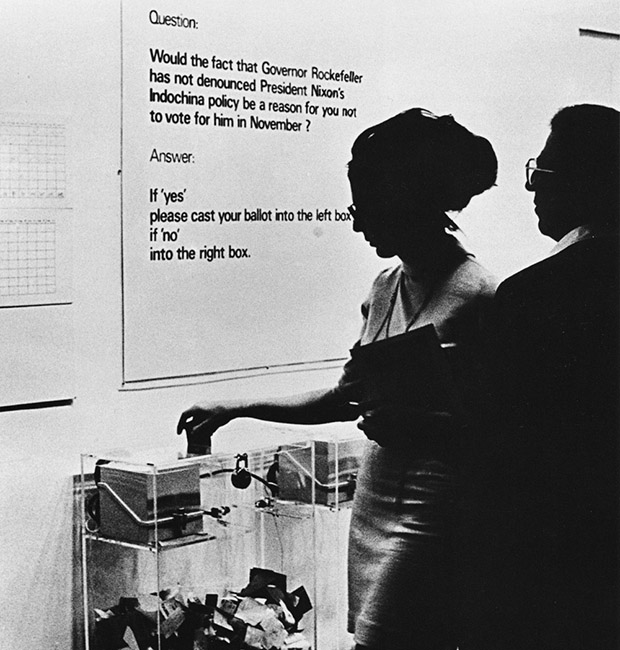

Hans Haacke’s MoMA Poll consisted of a sign, two transparent boxes, a photoelectric counting device and a set of ballot papers installed at the Museum of Modern Art’s group show, Information, curated by MoMA's associate curator Kynaston McShine.

As we explain in our Haacke monograph, visitors to the show, were asked to respond to the question Haacke posed: Would the fact that Governor Rockefeller has not denounced President Nixon’s Indochina policy be a reason for you not to vote for him in November?’

Haacke's inquiry, alluding to the USA’s covert bombing of Cambodia, was inflammatory enough, yet his direct reference to Nelson Rockefeller, the Republican governor of New York and MoMA trustee, demonstrated how contemporary art was beginning to turn against the bodies that nurtured it, in a movement known today as Institutional Critique.

It was not the first time Rockefeller had drawn the ire of contemporary artists. “One afternoon in November 1969, four members of the recently formed art collective the Guerrilla Art Action Group staged an action in the entrance lobby of New York’s Museum of Modern Art. Their ambition was to undermine the widely held belief that the institutions of art were aloof from politics, and they realized this by performing a stylized enactment of military-induced violence in the museum itself. Blood, concealed in bags beneath their clothes, made the performance more dramatic.

There is nothing new about artists adopting overt political agendas, but this protest was distinctive for its ambition to make art politically useful by criticizing the institutions of art – and this is the meaning of Institutional Critique. A leaflet accompanying their protest called for the resignation of the Rockefeller family from the museum’s Board of Trustees because of their alleged business involvement in the manufacture of weapons destined for Vietnam.”

While the Guerilla Art Action Group’s activities are remarkable, what is perhaps more important is the degree to which MoMA and other institutions tolerated this sort of criticism, exhibiting Haacke’s MoMA Poll months after the GAAG’s assault.

Of course, not all museums were equally tolerant. “In 1971, when the New York Guggenheim Museum controversially censored two artists on separate occasions,” explain our editors in Art In Time. The first again concerned Haacke again, whose retrospective was about to open when the director insisted that two artworks be removed, on the grounds that they were overtly journalistic and political.

“These works used publicly available data to chart the business dealings of local slum landlords. When Haacke refused to comply, the exhibition was cancelled. The ensuing controversy highlighted the issue of who is entitled to determine what counts as art or politics. Later that year, Daniel Buren was obliged to withdraw from the Sixth Guggenheim International Exhibition when other contributing artists complained that his large striped banner interfered with the display of their work. Buren’s intention was to undermine the assumption that museums offered neutral viewing conditions: his goal was to expose museums as ideological constructs.”

Nevertheless, art institutions have, on the whole, tolerated Institutional Critique, perhaps because of the way in which the works allow once stuffy public arts bodies to engage with newer artistic concerns in an apparently sympathetic manner.

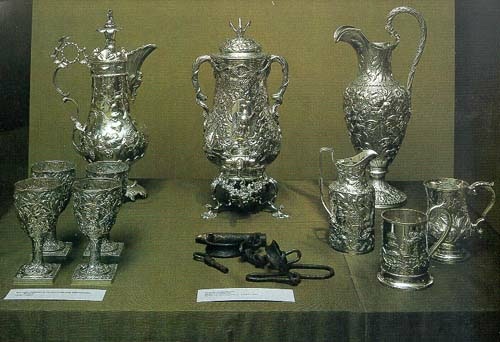

“In 1973, the American feminist artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles made a performance piece that involved cleaning the public spaces of the Wadsworth Athenaeum in Hartford, Connecticut, a gesture that highlighted the hidden labour that maintains the institutional display of art,” explains Art in Time. “In 1992, the African-American artist Fred Wilson curated an exhibition at the Maryland Historical Society in Baltimore that revealed the racial and class prejudices reflected by the museum’s holdings. In one display, ambiguously labeled Metalwork 1793–1880, he presented slave manacles alongside luxury silverware, thus radically questioning the histories that museums choose to narrate."

Indeed, Institutional Critique has breached the walls of the art museum and found public institutions to analyze. Earlier this year Haacke's Gift Horse, the sculpture of horse's skeleton adorned with a digital stock ticker, graced the Fourth Plinth in London's Trafalgar Square, drawing attention to the roles banking, war and pageantry play in British statecraft. Meanwhile, Sterling Ruby’s Supermax works make reference to the US prison system, developing an installation that is, in the artist’s words “packed, dense, confusing.”

Meanwhile, at Frieze later this year, the young Irish artist Uri Pattison, plans to install a series of digital billboards, more commonly used to display commercial and financial data, around the fair, feeding data gathered around the fair’s pavilion to the art collectors, in much the same way less high-minded traders draw crunch through numbers in markets around the world. Pattison might not be using acrylic polling booths, as Haacke once did, yet the results, in many ways, is the same.

For more on Institutional Critique and its place within art history order a copy of Art in Time here. For more on Hans Haacke get this book; for more on Sterling Ruby order our new monograph, and for more on Frieze, pre-order our new book frieze A to Z of Contemporary Art.