How Septime tore apart the restaurant hierarchy of Paris

Our new book describes how two young Parisians challenged the values of haute cuisine and created a whole new way of eating out

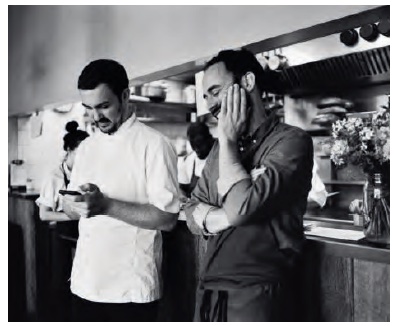

Bertrand Grébaut and Théophil Pourrait were always caught somewhere between the gutter and the Michelin stars. The pair grew up in Paris, and were enamoured of both high and low culture.

Pourrait had a passion for environmentalism; Grébaut loved graffiti; and they both adored food. Yet they weren’t foodies in the classic, Parisian, haute cuisine sense. As the author and filmmaker Benoit Cohen describes it in our new book, Septime, La Cave, Clamato, D'une île, “they spent their evenings and weekends enjoying innovative and inexpensive cuisine with natural wines, frequenting places like Yves Camdeborde’s La Régalade and Raquel Carena’s Le Baratin.”

At this point, in the late 1990s and early 2000s, many in Paris were beginning to question whether the high dining traditions established over 100 years earlier by pioneers such as Auguste Escoffier were still relevant to restaurants in the 21st century.

One figure raising these questions most vociferously was the French-born chef of Spanish heritage, Iñaki Aizpitarte, whose restaurant Le Châteaubriand both Grébaut and Pourrait admired.

“From the moment we arrived, we couldn’t believe our eyes,” Grébaut recalls. “The atmosphere was completely different from that of typical gastronomic restaurants of the time. The servers were people like us, unshaven, who we could talk to as equals; loud noises could be heard coming from the kitchen; there were no tablecloths and no frills. And the food was sensational!”

As Cohn explains in our new book, the pair “understood that a new type of restaurant – liberated, young and unfettered by traditions – was emerging. And they wanted to be a part of it. A new world of possibilities was opening up to them. For the first time, they imagined one day combining their talents.”

Grébaut had successfully retrained as a chef, graduating top of his year, while Pourrait had turned his hand to management, overseeing a 100-cover restaurant in the heart of Paris. They continued to work their way around the upper end of the Parisian restaurant scene, while dreaming of opening somewhere that wasn’t quite so elitist.

“The pair would often meet up after work and talk about the idea of opening a place together that was closer to their dreams,” writes Cohen,. “‘A place with first-class cuisine, a beautiful setting, friendly service and a list of natural wines that we love,’ sums up Théo. But before they began, there was one thing they still needed to do to complete their education: travel. Bertrand left to explore Asia for six months – Thailand, Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, China, Japan and the Philippines – while Théo moved to Italy, to Florence, where he travelled around the countryside meeting producers, winemakers and Tuscan breeders.”

Once back together again in the French capital in 2011, they set their ambitions in motion, setting up a small restaurant inside two, old knocked-together shops in Paris’s 11th arrondissement. They named it Septime after a stuffy restaurateur from an old French film; yet there was nothing pretentious or outdated about this place.

“Bertrand and Théo created the sort of place they would like to go: a restaurant that reflected their tastes and style; somewhere you could eat well and would be served well, with a wine list that was both innovative and carefully considered – a beautiful, unpretentious place,” writes Cohen. “That may seem a straightforward concept today, but in the early 2010s, it was fairly uncommon. Back then, most beautiful restaurants served mediocre food, and good restaurants rarely looked good.”

Septime, by contrast, was small, tasteful and inviting. The dining room occupied just 90 square metres (969 ft2), giving them enough space for 50 covers (later reduced to just 36), while the kitchen was a miniscule 18 square metre (194 ft2), offering room for just nine staff.

The walls were plain plaster, and in between them stood glass partitions and roughly hewn wooden tables. Septime looked like a bistro, but it offered much more than a tasty lunch or dinner.

“Theirs was a bistro that had, instead of a bar tap pouring beer, one which served orange wine: a table d’hôte with no tablecloths, no sommelier and no frills,” explains Cohen.

These weren’t gimmicks; the pair were very clear about their convictions. “The idea of a restaurant that was accessible, not elitist, was important to us from the start,’ says Pourrait in our new book. ‘We wanted to bring the gourmet restaurant within everyone’s reach, by offering food at fair prices. More selfishly, we wanted our friends to come and have lunch or dinner here.”

Not only did they win over their friends; they also convinced quite a few within the global restaurant community. A decade on from its opening and “Septime has become an important address in the world of French and international cuisine,” writes Cohen. It might not be the sort of place to please its stuffy namesake, but it's perfectly suited to the manners and tastes of the 21st century.

To find out more about Septime, as well as the other places Bertrand and Théo run, order a copy of Septime, La Cave, Clamato, D'une île here.