INTERVIEW: Dominic Bradbury on how Mid-Century Modernism took over our world - and why we're happy it did

'It was all so evocative, so mesmerising,' the Atlas of Mid-Century Modern Houses author says in this Christmas Holiday Long Read

To live in a mid-century home is, in some sense to live a dream. As the writer and author of our new book, Atlas of Mid-Century Modern Houses, Dominic Bradbury explains, these open-plan homes, often built from concrete, glass and steel, were inspired by the hopeful, post-war aspirations of a generation of architects, who imagined a newer, freer, more open way of organising our domestic lives, no matter who you were, or where you lived in the world from Australasia to Africa and, of course, America.

That dream was not wholly shared across the globe, yet, as Bradbury explains in this interview, the initial backlash against mid-century architecture has since given way to a renewed sense of value and historical importance. Read on to discover which houses Bradbury really admires, why he thinks mid-century architecture spread so far and wide, and what really surprised him in the making of this book.

Is there something that characterises mid-century architecture, (apart from the period in which it was built, of course)? Well, chronology is important. We were fairly strict on ourselves; the period in which most of the houses were built really does begin in the late 40s and 50s, and ends around 1970. We also wanted a really global span. However, yes, within that there are key characteristics that come through pretty much wherever they are. A lot are contextual but there are common characteristics.

We're guessing a sense of exuberance is one of them. There seems to be something joyful and optimistic about these houses. Well, the experience of the Second World War, which predates this period, was horrific for many people. People were looking for a new experience, and they were building on the lessons of pre-war Modernism, but doing it in a more playful way. So you see a lot more texture, colour and pattern in the houses, as well as structural forms on the outsides of buildings too. For instance, there are quite a number of round or geometric triangles and hexagons; there were lots of different things going on, and yes, there is this optimistic characteristic that carries it all through.

There was a real synergy wasn’t there in that many of the architects also designed the furniture inside. Indeed. I think that’s true for a lot of the architects, especially Scandinavians like Alvar Aalto and Eero Saarinen. It's actually more common in the fifties and sixties compared to the twenties and thirties, when some of the Modernist architects would stop at the interiors to some extent. It brings about a more cohesive quality.

One of the reasons I like this period is because a lot of designers and architects were crossing borders artistically as well as geographically. People like Gio Ponti in Italy would do anything and everything, from a skyscraper to a vase. There were no borders, no boundaries.

Was there a universal ideal for living coming to the fore? To some extent. If you talk about spatial planning, for instance, I think in the mid-century period you’re really progressing towards open-plan living. You’d have a universal living space, rather than having a separate living room and dining room. Even the kitchen is creeping into the living space and becoming more integral to the whole. So you start to see it, for instance, in John Lautner’s Elrod House. There, the kitchen is part of the heart of the house, literally.

There’s also a big push to inside/outside living. This is enabled partly by the evolution of curtain walls and lightweight steel structures that allow for large expanses of glass.

I think that’s a point of difference from the early Modernists. They had started to develop that idea, but it was taken much further in the fifties and sixties. There are plenty of Californian houses in the book, and they are really pushing that inside/outside living theme more than ever before.

What enabled the rapid production of these houses? I think it varied in different parts of the world. In America they were better placed to have access to materials like steel and glass, whereas over in the UK and in other parts of Europe we were still on rationing during the early 1950s, and that included building materials. So if you look at a lot of late forties and early fifties UK furniture, its making do with whatever materials tend to be around – which are fairly basic - and I think that’s carried through to construction to some extent.

One of the reasons Californians were able to take things forward quickly is that the whole American economy was so well geared up to industrial production through the war and they hadn’t had that wartime damage through bombing that we had had in the UK, or in other parts of Europe. You could argue that it took the UK and Europe to catch up to that level of refinement in terms of structure and engineering.

The book covers the whole world. What inspired global trends in this period? Well, architecture was certainly globalised. If you think of the growth of the magazine industry, for instance, people were reading more things from abroad, so there was more of a circulation of ideas and projects in that post-war period. More people were jumping on planes; travel became more possible and more affordable and accessible.

All the European émigrés who’d gone over to America were going back and forth; people like Richard Neutra and Marcel Breuer eventually went back to Europe and took on other projects. Also, architects were getting more and more international commissions. Gio Ponti, for example, was going off to South America quite a lot at this time, and a number British architects were working in parts of the Commonwealth, so I think generally there is more going on in terms of that cross fertilisation.

Also, if you look at the Scandinavian countries, they began to group together, and market themselves as a Scandinavian or Nordic collective.

When you look around the world, do you see elements of vernacular architecture feeding into the mid-century modern style? That’s interesting, because, on the one hand, you do have this push towards the global in the fifties and sixties, but on the other hand, you do have, in certain parts of the world, quite a strong vernacular influence. In the fifties and sixties you have the International Style [a term used to describe the prevalent, global, post-Bauhaus style of architecture], but then you have this strong local aesthetic on the other hand. Especially in Scandinavia, you have all the natural materials, such as wood, and a cabin-like aesthetic.

How did it manifest itself further afield, such as in Africa? There are some interesting things in Africa. You could call it colonial or tropical architecture. A number European architects working in Africa were trying to develop a version of tropical Modernism suited to the sort of European territories that were swiftly gaining independence. You have Jean Prouvé for instance, trying to develop these pre-fab buildings that could be used in French tropical territories, and you can make parallels with some of the things happening in Asia and central America and even Florida, where you have people like Paul Rudolph who was developing a sub-tropical Modernism, which was to do with the climate and conditions as much as aesthetics.

Did these countries produce their own architectural talents, or did Western architects travel to, and work in, these places? It was a bit of mix. People like Harry Seidler started off in Austria, went to North America, South America, then Australia, and is now viewed as one of the founding fathers of Australian mid-century Modernism. Once somebody like Seidler arrives in Australia, he tries to forge a contextual response to the place and its aesthetic. So it’s not just replicating what he might do in America or Europe, in Australia; it’s responding to the unique setting and place.

What did you learn from putting the book together? I realised just how much was going on in different parts of the world. Take Japan. Unfortunately, the Japanese cultural approach to domestic architecture is to replace houses fairly often, so a lot of the wonderful mid- century domestic architecture that was built there no longer exists apart from in the pages of this book.

Also, I think looking at places like Latin America, I was reminded of just how much was going on there. In Brazil and Mexico, for example, they brought their own ideas into the mix, with architects such as Luis Barragán, Oscar Niemeyer, and Lúcio Costa. There’s a really strong tradition of Modernism in Latin America, so it was interesting to learn more about that and see how strong and vibrant it was. People such as Félix Candela came through in that part of the world, doing amazing work in structural engineering, with heavily sculptured concrete.

Which houses gave you most pleasure to feature in the book? Houses that have a great backstory. That gives you something to latch on to, whether it’s the architect, the ideas or the owner, and so you learn a bit more about different parts of the world. I didn’t know how much there was in the UK from the fifties and sixties. I was finding things in Scotland that I just was not aware of before. Some of them were listed, some of them aren’t. I wondered if we’ve done ourselves a disservice in the UK by not talking enough about those great houses from the fifties and sixties.

Would you live in one? I would love to. Currently, I live in a period house with quite a bit of mid-century modern furniture mixed with arts and crafts. I think it’s interesting how important the mid-century influence is on contemporary architecture and design. Today, many architects are influenced by the designers of the fifties and sixties. I think that applies to lot of things, not just houses and architecture. Look at fabrics, textiles and graphic designs.

Some seem cheaper than you might expect, especially compared to London and New York property prices. Are there problems attached? They’re often quite experimental, so sometimes you get problems that result from that, or you find that there are structural issues that have to be resolved. But some of them stand up remarkably well and they do make beautiful spaces to live in. Back in the 90s some were still being knocked down by developers; now, we’ve wised up to the importance of these buildings. In the US and the UK we’ve become more aware of the monetary and historical value of those buildings. In the US you get houses being auctioned because they are on the level of artworks. So some come with conditions attached, and yes, some come with problems attached!

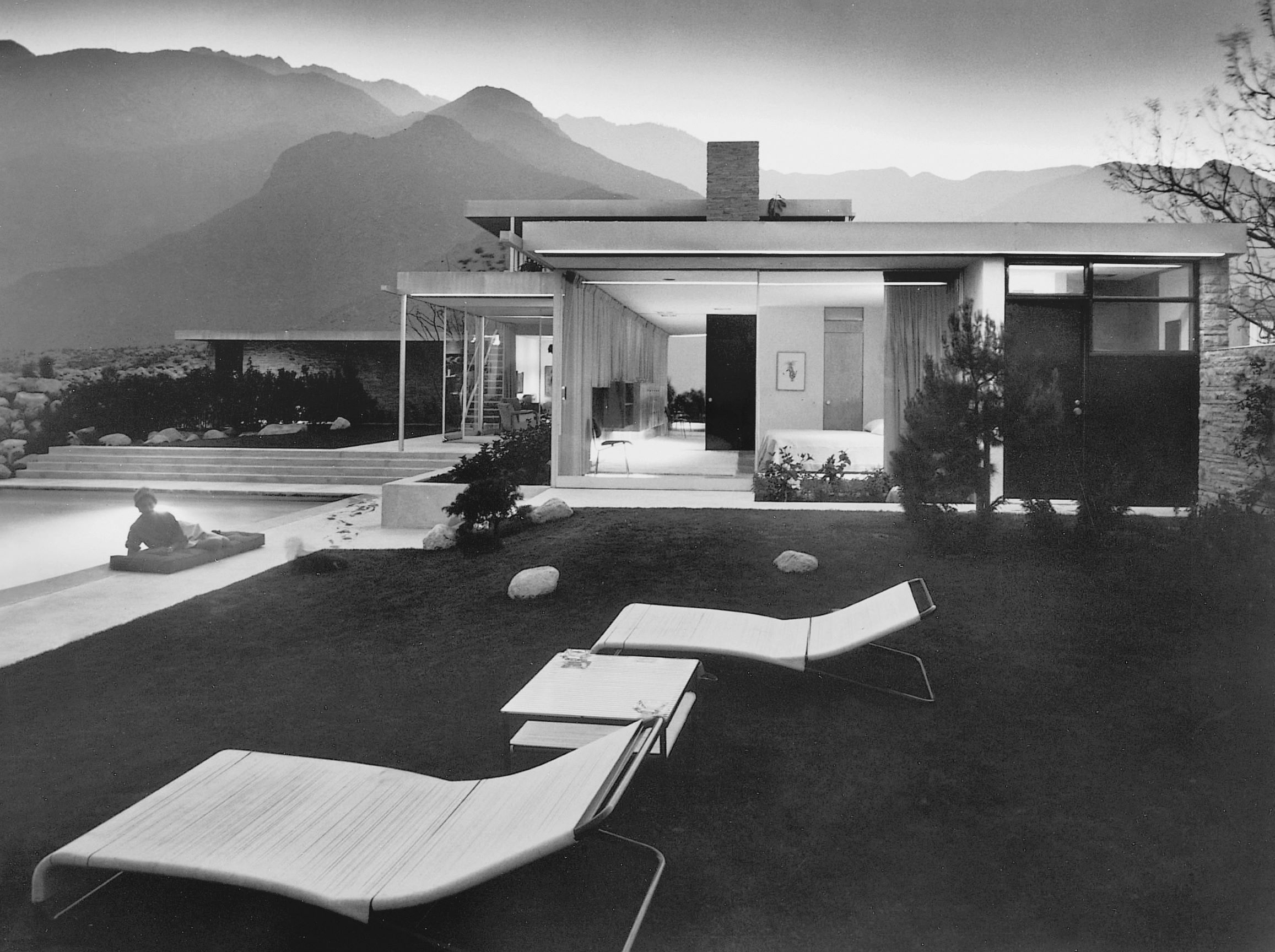

When did your own Mid-Century Modern love affair begin? Quite a while ago. I remember going to Palm Springs; that was the moment for me. In that resort town, You’ve got Neutra’s Kaufmann house, John Lautner’s Elrod house, Craig Ellwood’s Palevsky house, the Parker hotel, the Palm Springs Art Museum. It was all so evocative, so mesmerising. There are certain places like that that just really take hold of your imagination.

Interestingly I was in Columbus, Indiana recently, and that was quite similar, because you have the Eero Saarinen influence coming through with the Miller House, so you feel you’re on the pilgrimage trail of these amazing mid-century buildings. Occasionally you come across these wonderful centres of mid-century life.

Do you have a favourite? It’s very difficult to pick one. Eero Saraanen’s Miller House in Columbus is amazing; it’s in a beautiful setting and Saraanen worked on the interiors with Alexander Giraud and all the furniture is still in the house. It’s just this beautiful space with these beautiful views out.

I also like Maison Louis Carré by Alvar Aalto, a beautiful house in France on top of a hill. Carré was a gallerist and art dealer and he was going to choose le Corbusier, to stay in the French tradition, but met Aalto in Venice and commissioned him instead. It’s on top of a hill with a mono-pitch roof, which echoes the line of the hill. It’s also one of these total works of art: Alto did the interiors, the furniture, the lights, the door handles everything. It’s a real gesamtkunstwerk.

Then again, maybe I’d pick one or two of the East Anglian houses, in Great Britain. There’s the Ahm house in Hertfordshire; it’s the only house Jørn Utzon designed in the UK. The owner was a structural engineer at Arup working in the London office. He knew Jørn Utzon from the Sydney Opera House and asked Utzorn to send over plans of the house; the engineer took these plans and built the house himself. Its use of brick is beautiful, and it has a great inside/outside relationship. Recently, it was bought by a couple who have undertaken a restoration and brought some beautiful furniture in.

To take a voyage around the world through these pages is really the glory of this kind of format. You can pick up so many threads and trails.

Do you see today’s architects reference the themes and styles of mid-century modern? Some mid-century architects pre-empted today’s design concerns. With Scandinavian architects there is this green thread, this sustainability thread, with wonderful mid-century cabin and timber houses, which chimes with our renewed interest in sustainability.

There’s also a modesty of scale, which again, has an ecological aspect. A lot of mid-century houses were not giant McMansions. Even when they do go big, they’re often broken up into pavilions and smaller volumes rather than one big mass.

When you think of something like the Kaufman house in Palm Springs it’s quite large, but it doesn’t feel like a big house. I think that’s partly because you’ve got these different wings or spokes flying off from the centre. It never feels like a huge house; instead its relatively modest.

To see all the houses Dominic describes order a copy of the Atlas of Mid-Century Modern Architecture here. A fascinating collection of more than 400 of the world's most glamorous homes from more than 290 architects, the Atlas of Mid-Century Modern Houses showcases work by such icons as Marcel Breuer, Richard Neutra, Alvar Aalto, and Oscar Niemeyer alongside extraordinary but virtually unknown houses in Australia, Africa, and Asia. A thoroughly researched, comprehensive appraisal, this book is a must-have for all design aficionados, Mid-Century Modern collectors, and readers looking for inspiration for their own homes. Find out more here.