Meet Brian the Hunter - one of Jeremy Charles’s Wild Bunch

In his new book, the Newfoundland chef celebrates his best ingredient: his skilled, characterful suppliers

Jeremy Charles, the patron chef of the award-winning Newfoundland restaurant Raymonds, has managed to find culinary fame in the wilds of north-eastern Canada, not only thanks to the region’s incredible natural flora and fauna, but also via the men and women who catch, gather and bring that produce to his restaurant’s doors.

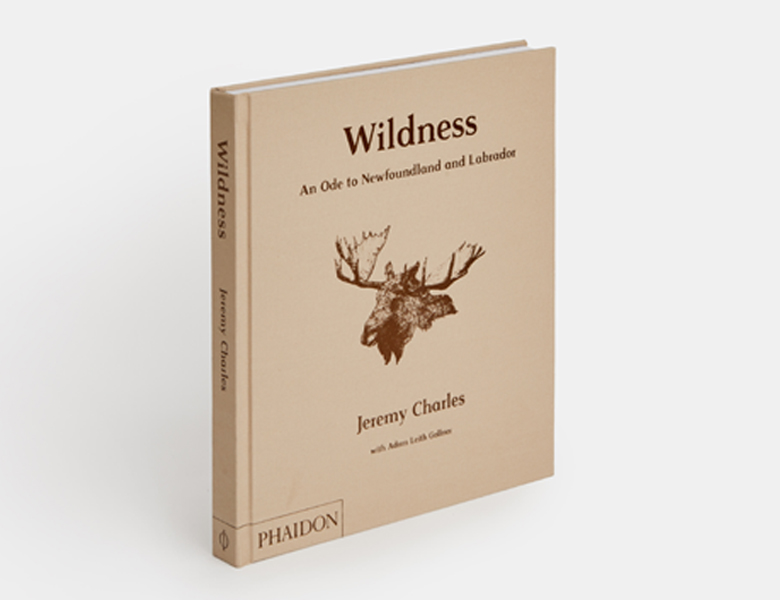

“Over the years, we’ve been able to build up a network of small suppliers who make it all possible,” he writes in his cookbook, Wildness: An Ode to Newfoundland and Labrador. “Without our suppliers, friends, and associates, who work on land and sea, and whose produce ends up on the plates at Raymonds and its sister restaurant, The Merchant Tavern, this book would not be possible.”

Some of them work full-time to stock restaurants such as the ones Charles runs. Others, however, see the delivery of supplies as an upshot of their other passions – an upshot, quite literally, in the case of the local geologist and partridge hunter, Brian Dalton.

“Partridge is the national bird of Newfoundland and Labrador,” explains Dalton in his guest essay, reproduced in Wildness. “Funny thing is: outsiders don’t really come here for partridge. Moose and caribou are what most tourist-hunters come for. Some outfitters offer partridge hunting as a sideline — but really, it’s a locals’ sport. Among our hunting fraternity though, it’s practically a religion.

“There’s a lot of walking, a lot of action, so a good day in the woods is a serious workout,” he writes. “You need to be fit—and you also need a hunting dog, of course. Pepper may seem like just a regular English Setter, but as soon as he sees me pick up that gun, he morphs completely. He becomes what he was bred to be. Hunting with dogs is a gentry tradition from England; there, it’s become more of an elitist niche, but here in Newfoundland and Labrador, it’s the privilege of the common man. Pointing, flushing, shooting. There’s a whole majesty to seeing that dog on point. The first aristocratic arrivals here must have been like, “Holy shit, there are tons of birds on this island.” And there still are.

“Hunting is a silent communication between man and dog. The man trains the dog — but the dog also trains the man. It’s a bond, a camaraderie, a partnership. Pepper starts quivering and panting as soon as we head out. “We’re nearly there, Pepper boy!” I’ll say. He replies with a low howl. He starts crying or moaning gently as soon as we’re on the barrens. He’s ready to go. He loves it. It’s his reason for being. And he’s bird-crazy: pigeons in the street, crows flying overhead, a bluejay on a birdfeeder. I can see him thinking, “Where the birds at?” when he gets out of the pickup and bounds off happily, almost grinning. Jeremy, Pepper, and I often head out to hunt in an area around an hour’s drive southwest of St. John’s. It’s some of the southernmost tundra in the world. The terrain is so striking; it’s called the barrens, it looks barren, but it’s anything but barren.

“When you get in close, you can see that it’s quite alive, full of berries, soft caribou moss, patches of Labrador tea. The birds make nests in the pockets of green shrubbery and ferns, among the stunted juniper and spruce trees, only coming out to feed on berries. Partridges are slow to get off the ground—but they’re well camouflaged. They like to stay low, and their main defence is to hide. You could walk by ten of ‘em and not even see ‘em. The dog is what finally stirs them up, making them bust and go to wing.

“You can tell Pepper’s getting birdy by the way his tail starts going. He smells the air and the ground and says, “This is a place of interest.” Not everybody would be able to read his signs and work him right. He might be saying, “Let’s work this area over.” Unless you can recognise those signs, you’d barrel right through it. Pepper walks ahead, nose up to the wind. He works way out in front of me. His job is to pick up the bird’s scent. When he senses something, he freezes, then waits for me to catch up. I come up and release him, and he flushes out the bird, causing it to fly up into the air. At that point, I shoot.”

You can see the delicious fruits of those trips, with accompanying recipes, in Wildness. Order your copy here.