Why does Monica Bonvicini like smashing things up?

Whether it's shattered safety glass or hammered dry walling the Italian artist sees the beauty in destruction

Plenty of artists, from Michelangelo to Agnes Martin, have destroyed their own art. Some, like Gustav Metzger have placed destruction at the central element of select works. Yet no one does smashing quite like Monica Bonvicini. The Italian-born, Berlin-based artist approaches the modern, built environment with a critic’s eye and a vandal’s arsenal. From the broken glass box of White (2003), and the shattered glazing of Stairway to Hell (2003), through to the punctured walls of her video, Hammering Out An Old Argument (1998), here’s an artist who makes from the breaks. But why does she distress her works like this? It’s a question the artist answers in the interview section of our new monograph. Here’s how she sees it:

"I have often said that there is no construction without destruction. I don’t think that artists just create things out of their own flowery fantasies. As Lenin once said, the aim is to be more radical than reality is. Try that!" Commenting on her propensity to smash glass Bonvicini says:

"That’s what glass is there for in the first place. Like the glass cube on the first floor of Stairway to Hell (2003) in Istanbul, or White (2003). In general, though, I’m not very happy with the aesthetic result of my smashing glass. The process has a lot to do with the force applied to the hammer, and I’m not very strong. The best results I can manage are nice, perfect circles, and of course that’s not something I like.

"Many of the reviews of the smashed glass pieces mistakenly say that I used a gun to shoot and break the glass. This is not accurate at all. To shoot a gun requires a totally different approach. Its actions relate to different issues, its violence is detached and evokes issues I am not interested in talking about. I’m using a hammer, not a gun, not a stone. There is a sense to that. I’ve actually also applied some vandalism to my own works early on such as in I Believe in The Skin of Things as in That of Women (1999), or thrown paint on drawings, staining so to speak, what I’ve drawn, as in, for example, The Greater The Pleasure or Desire (2006). So, yes, destruction is surely inherent to creation. To create and to destroy are two sides of the same coin."

Yet why is it always the materials of architecture, and modern architecture at that she feels drawn to destroy? It’s an idea Professor Janet Kraynak explores in the survey section of our new book too.

“Plastered and Hammering Out (an old argument), disrupt, intervene into, and otherwise compromise the built environment,” Kraynak argues. “But their attack is as much aimed at ideas in and of architecture as at its existence as a physical entity. In short, architecture understood in these terms represents a discursive field – one inhabited by language, by symbolic meanings, by ideology – that must be deconstructed or, in some cases, destroyed. Hence the physical violations that Bonvicini performs against architectural elements: ‘hammering out’ or being ‘plastered’ are both terms with double meanings, a play on language that lends itself to literal and figurative readings.”

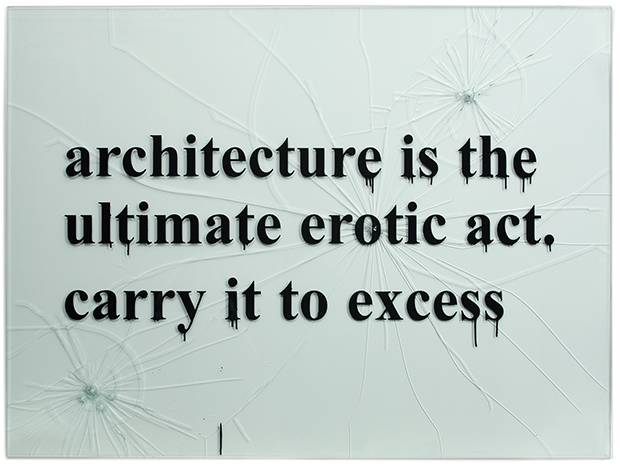

Kraynak explores this further a couple of paragraphs along: “In White, as in numerous other ‘smashed glass’ works (such as Stonewall 3, discussed below), Bonvicini conjures the thinking of architectural theorist, Bernard Tschumi, who famously wrote that ‘architecture is the ultimate erotic object, because an architectural act, brought to the level of excess, is the only way to reveal both the traces of history and its own immediate experiential truth.”

It takes an artist like Bonvicini to link these vandal-like blows to the erotic, controlling nature of the glass-skinned buildings we now take for granted. To learn more about Bonvicini in five key works, go here; for a richer understanding of her life and work buy our new monograph here.