How Lucian Freud, Martin Parr and Annie Leibovitz captured the Queen

To mark the jubilee, we look at how three very different artists pictured Her Majesty

Martin Parr is not the kind of photographer to stand on ceremony. “Whether photographing a stranger, a friend, Her Majesty the Queen, or other public figures, Martin approaches each in much the same way,” writes the curator Phillip Prodger in Only Human: Photographs by Martin Parr. “His pictures are often humorous, but the people they portray transcend their comic circumstances.”

Parr’s photograph of Queen Elizabeth II, which appears in Only Human, was taken in 2014, when the British head of state was visiting the Drapers’ Livery Hall in central London, to mark the Drapers' Livery Company’s 650th Anniversary. It’s a simple candid shot, which doesn’t elevate Her Royal Highness; in the photograph she’s faceless and dwarfed by her attendees, her Bentley State Limousine, and the raised phones of onlookers on the pavement opposite.

Some might see the image as unwarranted, and even disrespectful, but Parr and the Royal Household appear to be on good terms; in 2019 he sent the Queen a dedicated copy of Only Human, writing, on the title page, that he was ‘Your Majesty’s most humble and obedient servant’; last year RHR repaid the complement, when the photographer was recognised in the Queen's birthday honours with a CBE.

The painter Lucian Freud had a more complicated relationship with Buckingham Palace. In 1977 the painter rejected a CBE, but later took both a Companion of Honour and an Order of Merit from the head of the British state. Why this vacillation? Freud is quoted as reasoning, “I remember my friend (the ballet dancer and choreographer) Freddie Ashton said, a long time ago, people are always asking me whether to accept honours or not and he said: ‘I’d accept a bottle of gin’.”

It’s unclear whether a litre of Gordon’s ever made it way from SW1 to Freud’s studio, but in 2001 the painter did receive another Royal honour, as our book, Lucian Freud: A Life, notes.

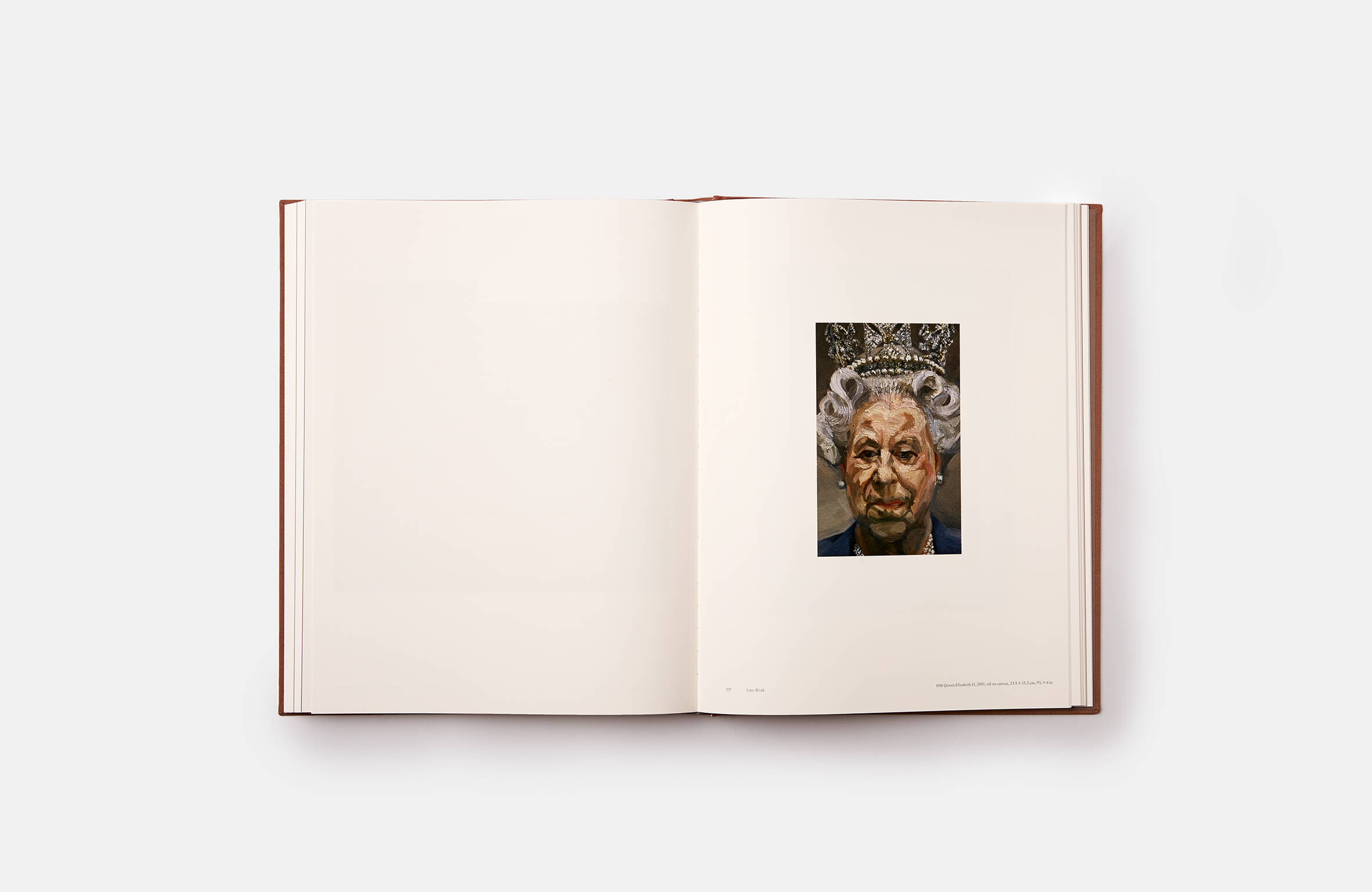

Lucian Freud's painting of the Queen, as it appears in our two-volume set on Freud

“He painted Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II and donated the work to the Royal Collection,” writes author Mark Holborn. “The Queen has been the subject of numerous portraits over the course of her reign, beginning with Cecil Beaton’s official photograph for the Coronation in 1953, made in a studio against a backdrop of Westminster Abbey. Just before she succeeded to the throne, she was photographed by Dorothy Wilding. In 2007 and 2016 she was the subject of photographs by Annie Leibovitz. She was painted by Pietro Annigoni, and sixteen silkscreen portraits were produced by Andy Warhol.

“Freud’s small portrait, which can be measured in a few inches, was painted in a restoration studio for the Royal Collection in St James’s Palace. Her diamond and pearl diadem was worn by a courtier at sittings. David Dawson photographed the Queen and Freud at work on the painting. Though some commentators felt the picture to be unflattering, Adrian Searle of the Guardian said the work was ‘the best royal portrait of any royal anywhere for at least 50 years’.”

Author Martin Gayford concurs in his commentary on this portrait in our two-volume Lucian Freud book. "There was no specific painting from the past that guided HM Queen Elizabeth II. Naturally, however, Freud was aware of innumerable pictures of kings and queens, stretching back to Holbein and beyond," writes Gayford. "He responded by underlining her status in a way that is almost jokey. Like a monarch in Alice in Wonderland or on a playing card, the Queen is wearing a crown. Freud admitted that he included this headgear partly because he ‘had always liked the way her head looks on stamps’. However, it was also because he ‘wanted to make some reference to the extraordinary position she holds, of being the monarch’. The royal portrait is only 9 inches by 6, a little picture; but Freud explained that his ambition was ‘to make a big small painting’. This was a perennial aim: even a tiny image was intended to have a monumental effect."

You can see the sitting in Lucian Freud: A Life, and the painting in our two-volume Lucian Freud book, while the Annie Leibovitz images from 2007 appear in Annie Leibovitz: at Work. In the latter book, Leibovitz explains how she felt she had an advantage over British portraitists, as “ It was OK for me to be reverent. The British are conflicted about what they think of the monarch,” she goes on. “If a British portraitist is reverent he’s perceived to be doting. I could do something traditional.”

The Queen photographed by Annie Leibovitz, as featured in Annie Leibovitz: Portraits 2005-2016

Nevertheless, Leibovitz royal appointment wasn’t entirely trouble-free. In early calls with the Palace, Leibovitz admitted she was influenced by Helen Mirren’s performance in the 2006 movie, The Queen, “and I couldn’t help mentioning how much I liked her character in that film,” the photographer writes. “There was a long silence on the other end of the line.”

Ever the professional, Leibovitz researched earlier portraits, including Freud’s work, as well as wardrobe options and potential settings in Buckingham Palace, where the shoot was scheduled to take place. The photographer was given just 25 minutes with the Queen, and planned the shoot meticulously, from lighting set-ups to clothing choices. Nevertheless, on the day, not everything went to plan.

“The Queen was about twenty minutes late, which we thought was a little strange,” she writes. “When that happens, you never know if it can be made up on the other end. My five-year-old daughter, Sarah, had come with us, and she curtseyed and offered the Queen flowers and I introduced my team. At this point I was in shock. The Queen had the tiara on. That was not the plan. It was supposed to be added later. The dresser knew that. The Queen started saying, ‘I don’t have much time. I don’t have much time,’ and I took her to the first setup and showed her the pictures of the gardens.

“I knew how tight everything was, especially with the loss of twenty minutes, and I asked the Queen if she would remove the tiara,” Leibovitz goes on. “(I used the word ‘crown,’ which was a faux pas.) I suggested that a less dressy look might be better. And she said, ‘Less dressy! What do you think this is?’ I thought she was being funny. English humour. But I noticed that the dresser and everyone else who had been working with her were staying about twenty feet away from her.”

Leibovitz is, of course, used to citations such as this, having photographed many of the world’s most famous people, and knows how to work with what she’s got.

Annie Leibovitz at Work

“We removed the big robe, and I took the picture of the Queen looking out the window, and then I said, Listen, I was a little thrown when you first came in and I have one more picture I’d like to try, with the boat cloak. We went back into the anteroom where the gray canvas backdrop had been set up and she took off the tiara and put on the cloak. That’s the shot we digitally imposed on pictures of the garden. The standing figure in the dress with the stole was also done against the grey backdrop and then put in the White Drawing Room. The real pictures of her in the drawing room are the ones where she’s sitting. I forgot to shoot her standing there. I was nervous. Right after we finished, I went up to the press secretary and said how much I loved the Queen. How feisty she was. Later I mentioned to a couple of friends that she had been a bit cranky, but it was nothing unusual. What was remarkable about the shoot, and I wrote the Queen a note about this later, was something the BBC missed: her resolve, her devotion to duty. She stayed until I said it was over.”

Lucian Freud: A Life

To see the images mentioned order a copy of Annie Leibovitz At Work here; and a copy of Annie Leibovitz: Portraits 2005-2016, here you can also buy Only Human: Photographs by Martin Parr here, and Lucian Freud: A Life here., as well as our two-volume Lucian Freud monograph, here.

Only Human: Photographs by Martin Parr