The volcano that shaped Slippurinn

The eruption of Eldfell almost put an end to life on the Icelandic island, Heimaey. So why does the chef Gísli Matt find the volcano comforting?

Volcanoes make and break the Westman Islands. This archipelago lies just south of mainland Iceland, and “consists of seventy to eighty volcanoes both above and below the sea,” explains the chef and author Gísli Matt in Slippurinn: Recipes and Stories from Iceland. “They have been formed by eruptions over the past ten to twelve thousand years, so an eruption was not completely out of the blue.”

Up until the early 1970s, there hadn't been any volcanic eruptions on Heimaey – the largest, oldest geologically and only permanently inhabited island – for five thousand years.

“There were fears that Helgafell [once the island's only volcano] would one day erupt again, but the eruption in 1973 was to the side of Helgafell, and created another volcano 200 metres (over 650 feet) high,” the chef explains. “Called Eldfell, the new volcano took the place of what had been a meadow.”

Such a huge eruption could have wiped out human life on Heimaey, but, as Matt explains, “it was the sea that saved us. Those who stayed behind, plus a crew of volunteers from the mainland, pumped seawater on the lava to solidify it – something that had been done on a smaller scale during eruptions in Hawaii and at Mt. Etna.

“A team called The Suicide Squad even worked on top of the active lava flow, suffering burns while laying the pipes that brought water from the harbour. By July, the flow of lava had stopped advancing, though two-thirds of all of the houses in town were either swallowed up by lava or badly damaged. Nearly everything else was buried in ash. By some miracle, the harbour, the lifeblood of the community and one of the centres of Iceland’s fishing industry, was saved.”

“My mother’s family went to Reykjavík for several months while the town was rebuilt,” writes Matt. “Many never returned and still have a hard time visiting after losing everything that day. Of the island’s 1,350 houses, 417 were destroyed by lava and another 400 or so were damaged. Still most of the population gradually returned and helped rebuild Heimaey and get the fishing industry back on track. Without it, few would have returned.”

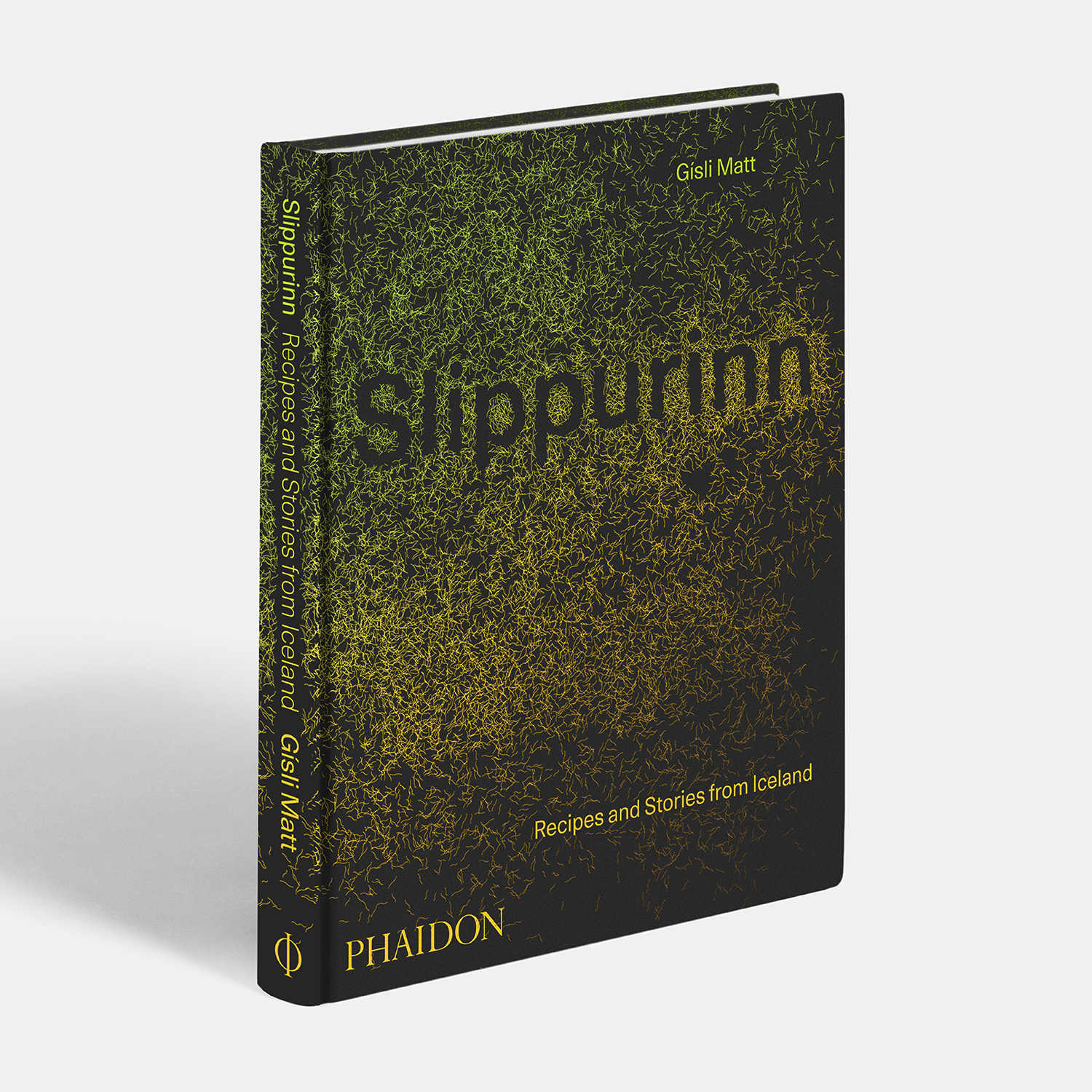

Matt himself was born on Westman islands in 1989, and 2011, after a stint on the mainland, he returned to Heimaey to found Slippurinn with the help of his family, in an old machine workshop in the island’s shipyard.

The internationally acclaimed restaurant followers the slow food philosophy, which prizes tradition and local produce. This isn’t easy on an island like Heimaey; Eldfell put an end to most of the farming here, and now only one, small organic vegetable farm on the island serves the restaurant.

However, the volcano also helped Matt and co. They’ve foraged wild ingredients on the island’s lava flows, drawn heavily on the fishing industry the eruption spared, and drawn solace from the sleeping giant that formed, and could reform the island. “The volcano that towers over our restaurant is a constant reminder of our place in the natural world,” writes the chef. “We know its power and how insignificant we are against it. In a way, it’s comforting.”

To find out more about this chef, his environment, outlook and his fascinating restaurant, order a copy of Slippurinn here.