The foraged plants that bring flavour to Slippurinn

The chef at this incredible - and incredibly remote - restaurant unearths a wealth of tasty ingredients in an austere environment (though we're still not sure about 'seaweed beard'...)

Heimaey, the largest island in Iceland’s Vestmannaeyjar archipelago, is hardly a lush, verdant, tropical garden of Eden. Very little farming takes place here, and many inhabitants left the island following the eruption of the Eldfell volcano in 1973. However, for those who remain, Heimaey affords quite a bit of tasty nourishment, via its plant life - at least for those who know where to look.

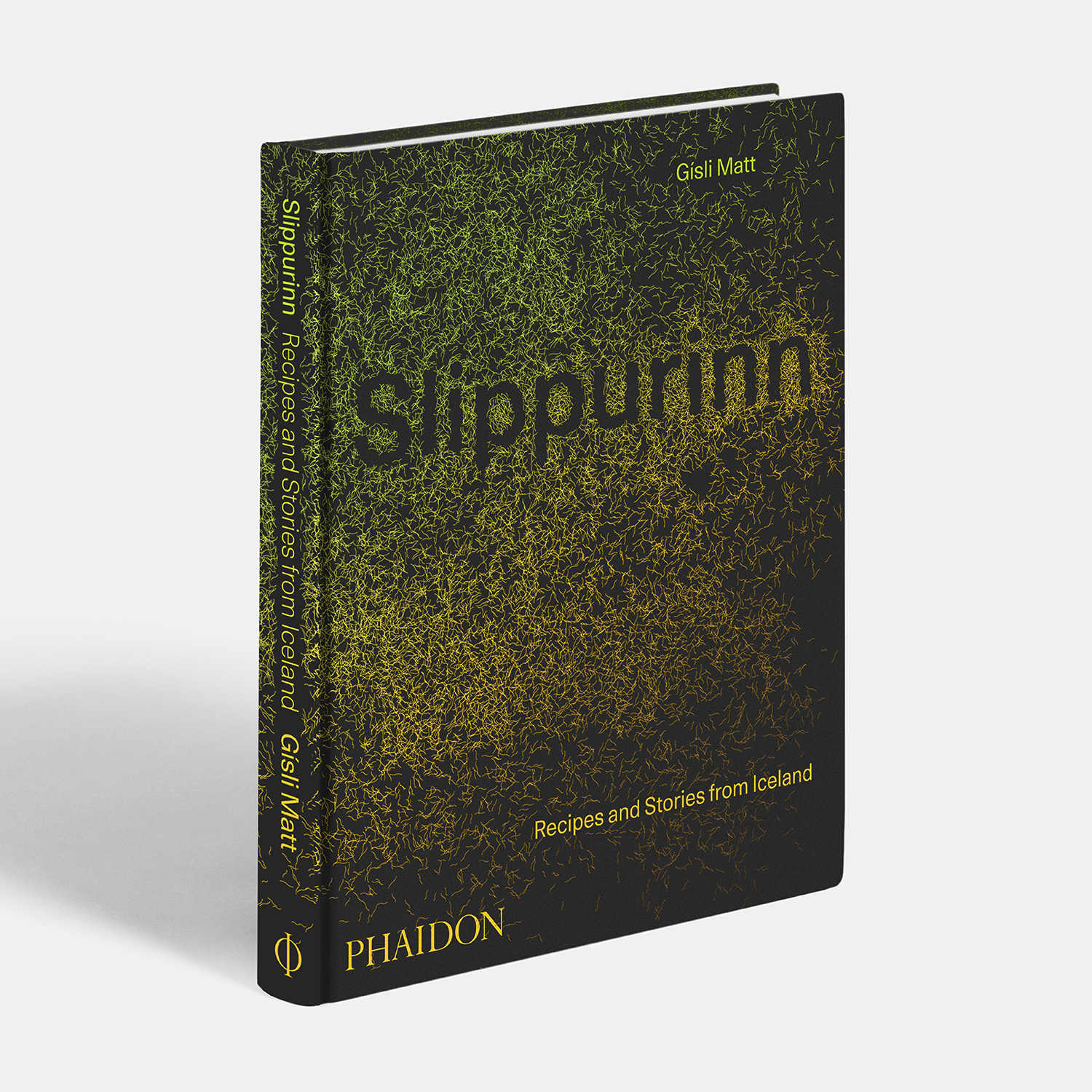

“In isolated corners of the country, including our archipelago, the places far from Reykjavík and Akureyri, where supermarkets are smaller or non-existent, our parents and grandparents continue to pass down this knowledge to us,” writes patron chef Gísli Matt in Slippurinn: Recipes and Stories from Iceland. “We’re fortunate for that, more than we probably realise, and we must not take it for granted.”

Matt returned to the island in 2011, to open his restaurant Slippurinn in an old machine workshop in the island’s boatyard. Since then, he has taught himself and his kitchen brigade to recognise the foragable plants found around the restaurant.

“Several times a week, most of the kitchen team from Slippurinn will go foraging together. It’s as much a part of working at the restaurant as prepping or dinner service,” he explains. “Each trip is usually focused on a particular plant or two, usually found growing near each other. Even though our season is short, with the size of the restaurant we need to gather a lot of plants and we spread out across as much of the island as possible.”

Sometimes they’ll find plants in the lava field that the volcano left behind, or in the houses it buried. On other occasions, Matt will have to head out to forage in the thick grasses that cover the outer islands, or take a trip in his father’s fishing boat to harvest seaweed in tidal pools and isolated coves.

The appeal of some of the plants is pretty obvious. “Arctic thyme (Thymus prae-cox) has a flavour of rich lavender with hints of honey and thyme,” says Matt. “The smell of it takes us directly to the height of the summer. In Vestmannaeyjar it only blooms from around late June to late July. At its peak, its small neon-pink flowers blanket grassy fields and hillsides, so we gather as much as we need for the year during that time. It’s good for the blood and for colds and is mostly used for tea or sometimes it’s mixed with salt and used as a rub for meats.”

Others sound like they’re more of an acquired taste. “Sea truffles (Polysiphonia lanosa) have a soft, almost hair-like texture, which is why in Icelandic their name translates to ‘seaweed beard’, which makes them sound a little off-putting, but they’re quite delicious,” the chef assures readers. “They have the taste of truffles merged with the taste of the seaweed, both strong flavours that somehow seem to mellow each other out.”

His new book lists dishes that use these wild ingredients and others, such as lovage, sorrel, spruce and even rhubarb, the last of which was introduced to Iceland, and responded so well to its austere environment, it now grows pretty much everywhere.

The season for these wild plants might be short, and the bounty might not be so obvious to untrained foragers, but the chef feels the island is, in its own way, paradise. “We are privileged to live in a pristine environment,” he says, “where every field or pile of rocks can be an edible garden.”

For a fascinating look at the plants Matt forages and the recipes that can be made with them, order a copy of Slippurinn here.