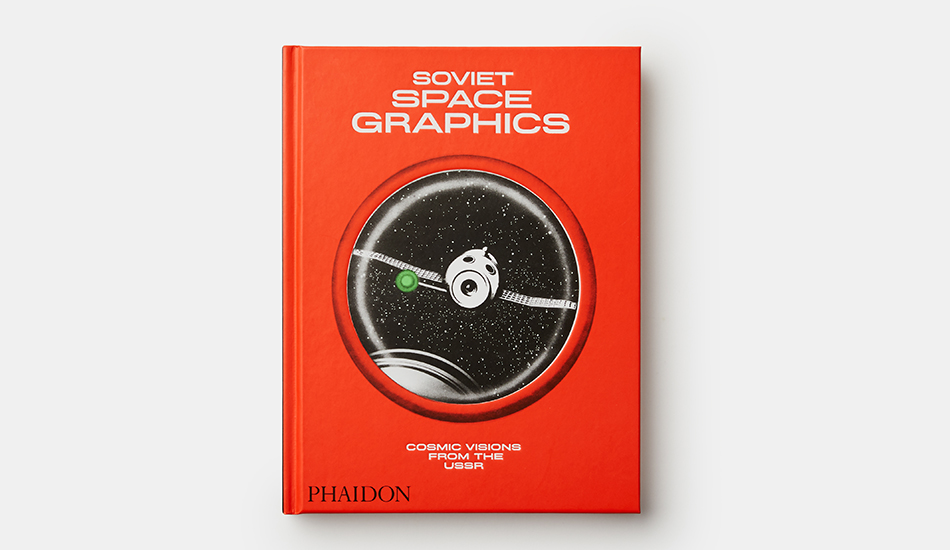

All you need to know about Soviet Space Graphics

How did the Communists picture the Cosmos? See the final frontier from the Soviet side of the Iron Curtain in our new book

The United States might have won the Space Race, yet there was a time when the US was in second place, behind a strident Soviet Union. As Alexandra Sankova the director and founder of the Moscow Design Museum, explains in hew book, Soviet Space Graphics: Cosmic Visions from the USSR, the Soviets not only launched the first satellite, put the first person into space, and conducted the first space walk, launched the first lunar probe and put the first dog in to space; it was a Russian scientist who first truly figured out how man might venture into the Cosmos.

“The advancement of Soviet space travel and exploration is inextricably linked to the work of Konstantin Tsiolkovsky,” she writes. “As early as 1903, Tsiolkovsky calculated a velocity required to take a spacecraft into orbit around the Earth using liquid oxygen and hydrogen as fuel. Due to his rather reclusive lifestyle working as a teacher on the outskirts of Kaluga, in western Russia, many of his early works were written in relative obscurity. However, the October Revolution of 1917 signified a major turning point in the dissemination of Tsiolkovsky’s ideas; for a new government looking to inspire a national awakening of pride and superiority, the scientist’s humble background and pro-Soviet ideology provided the perfect narrative.”

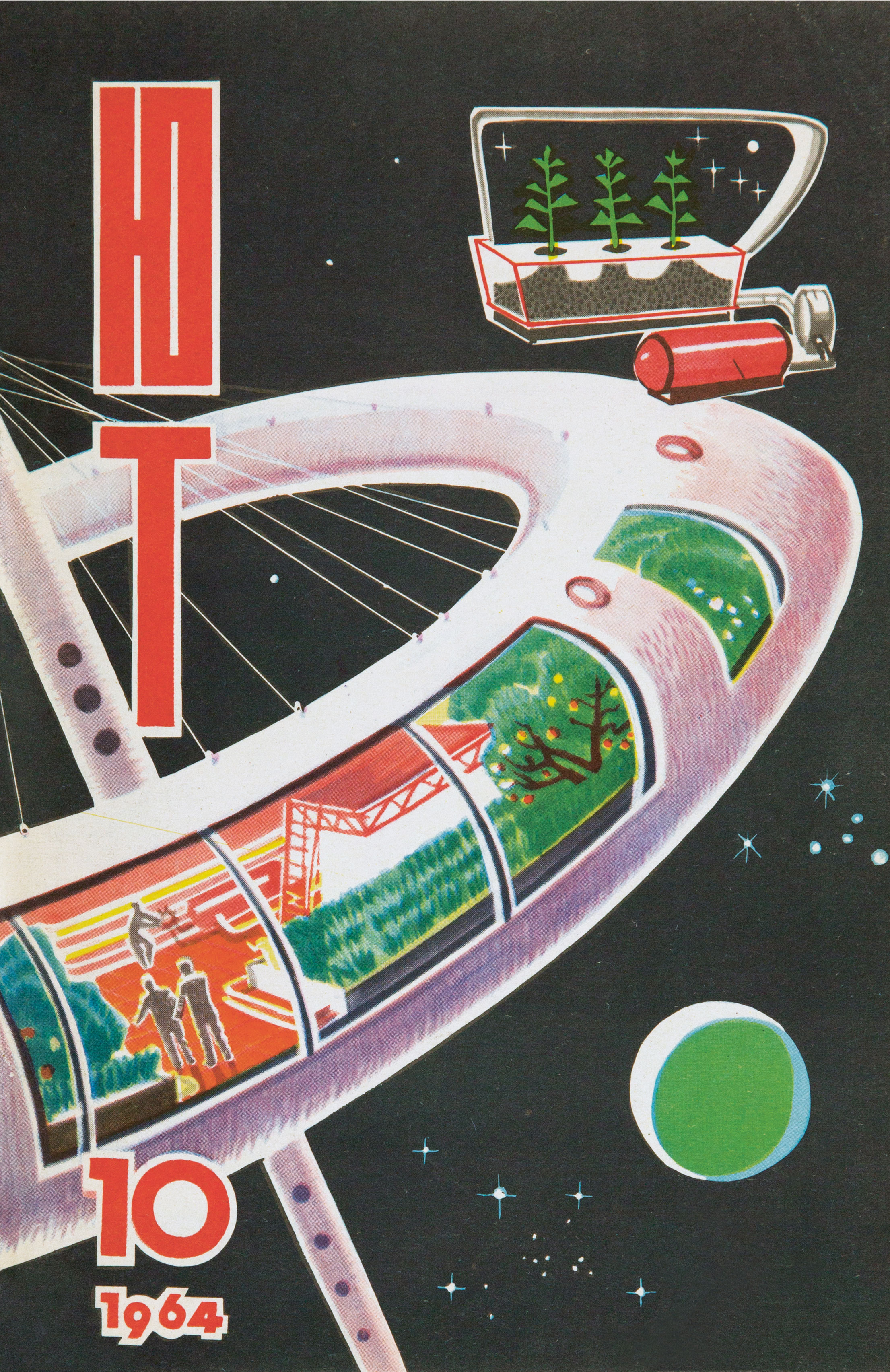

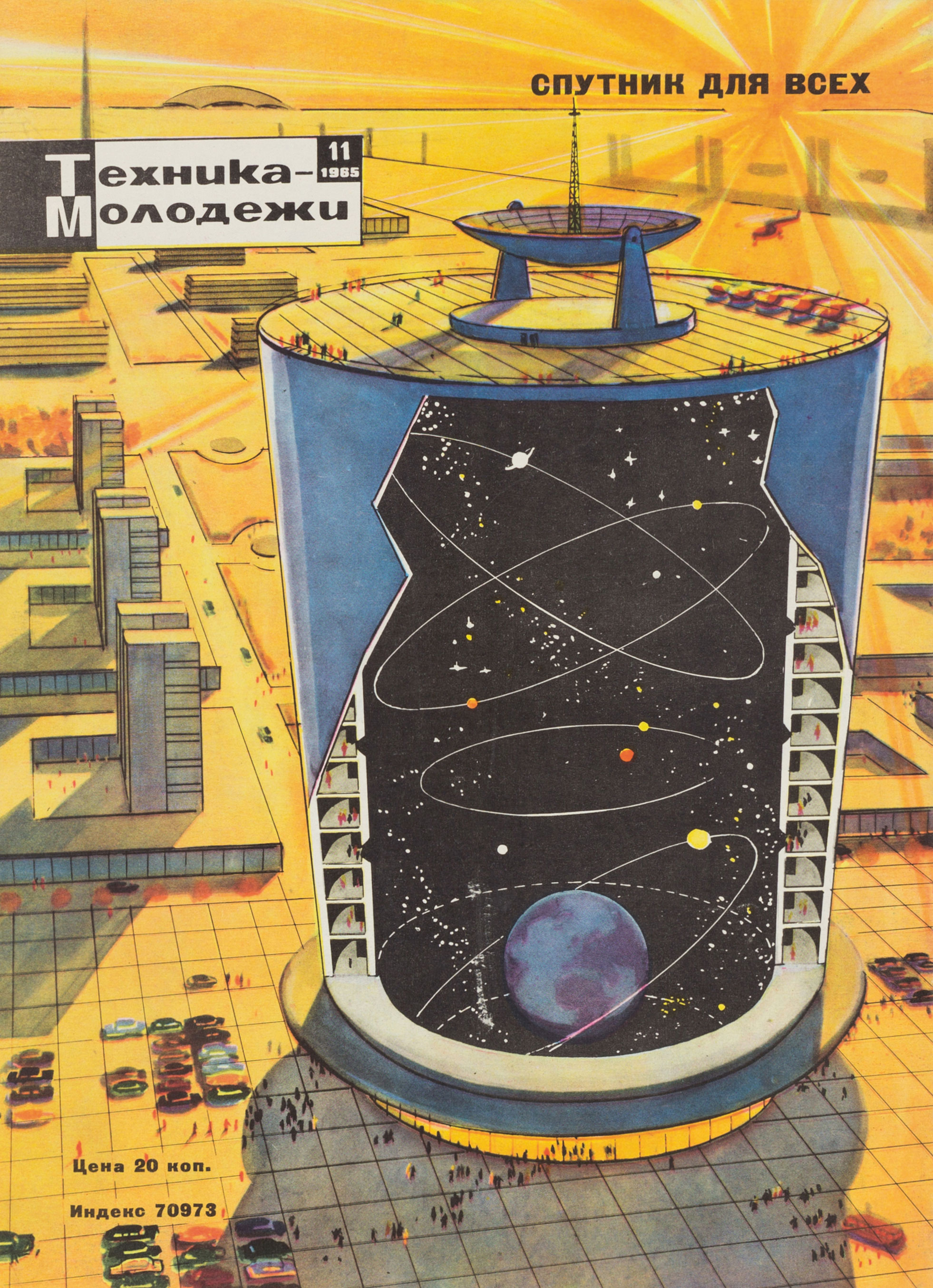

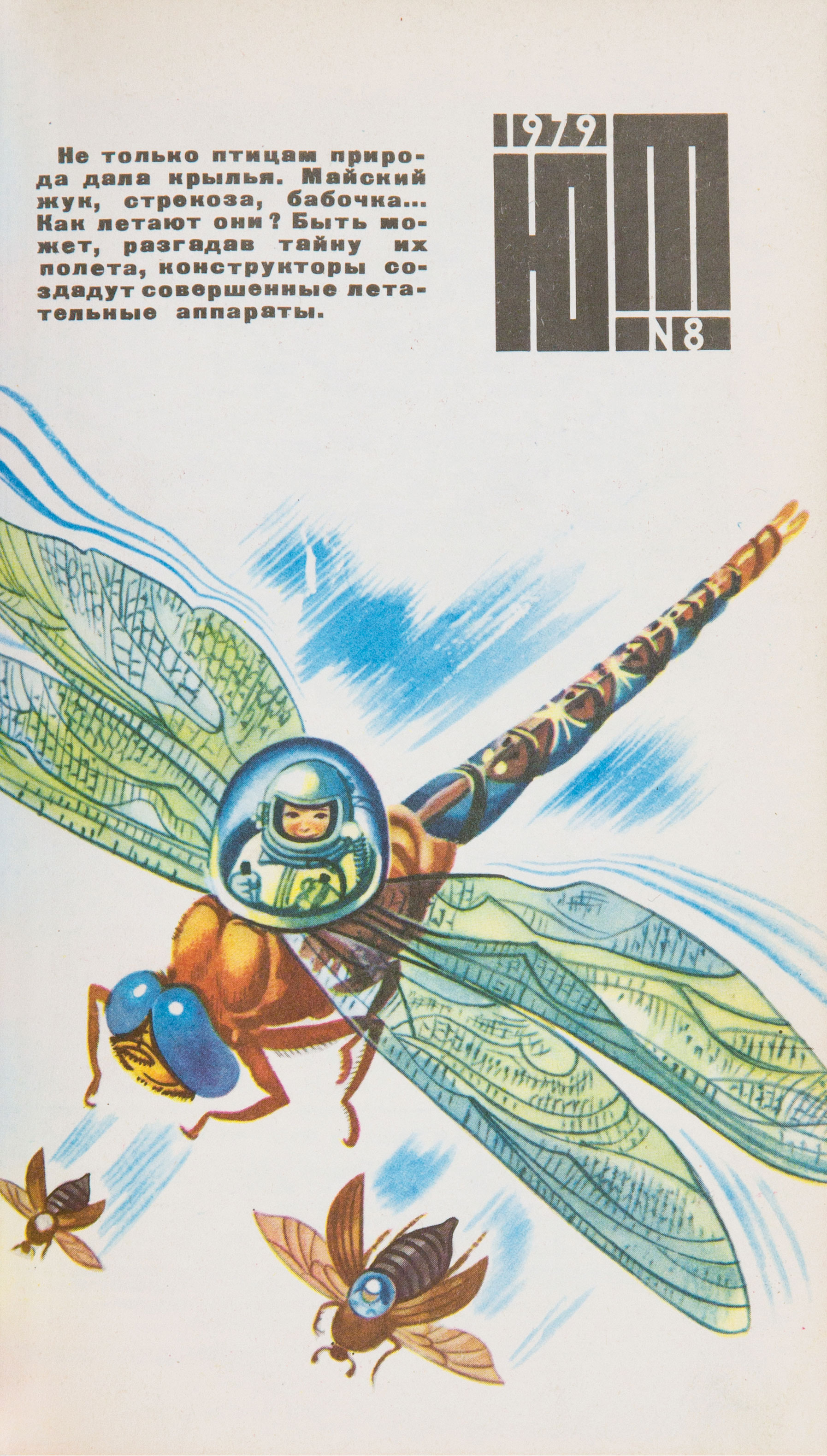

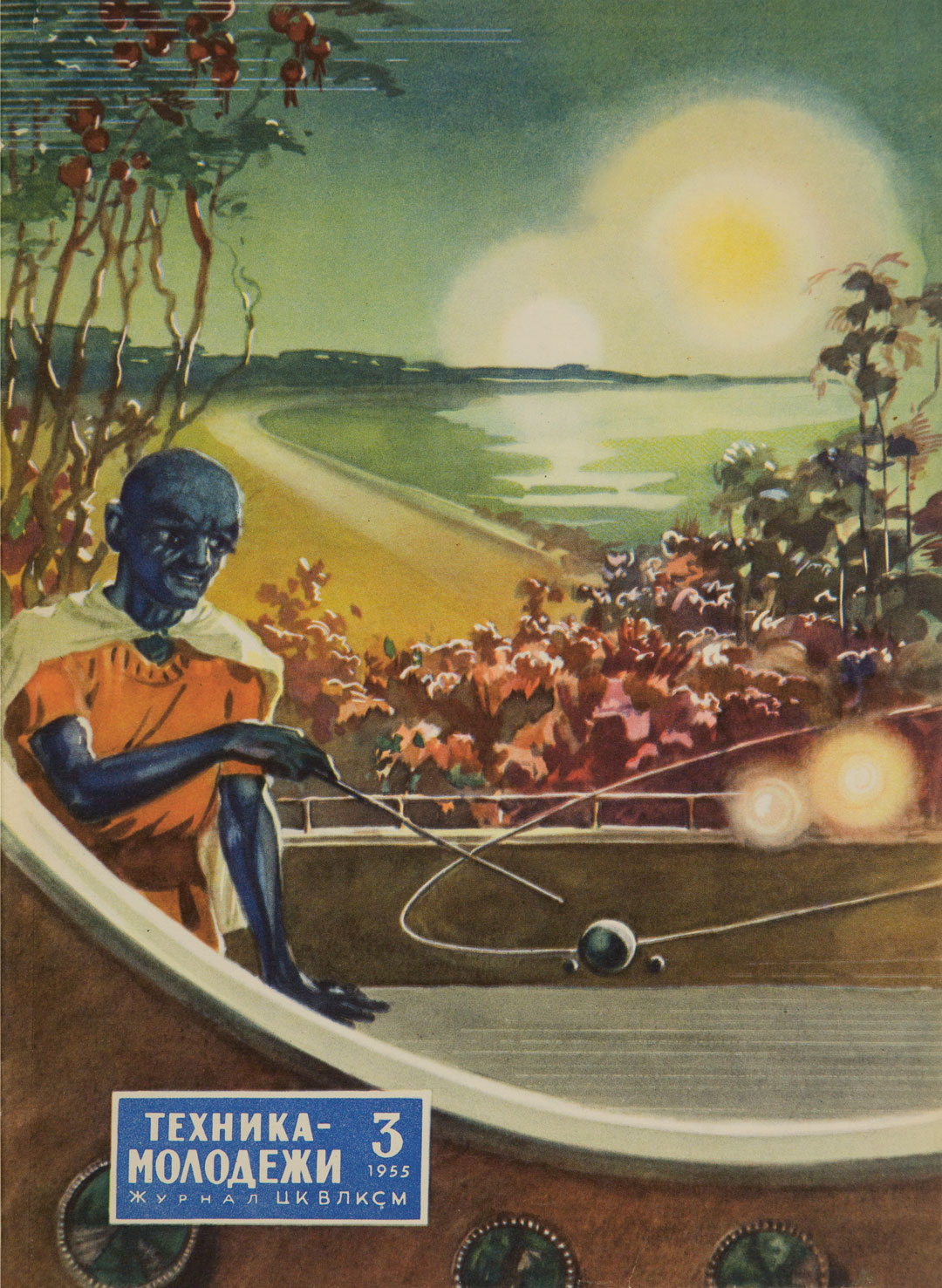

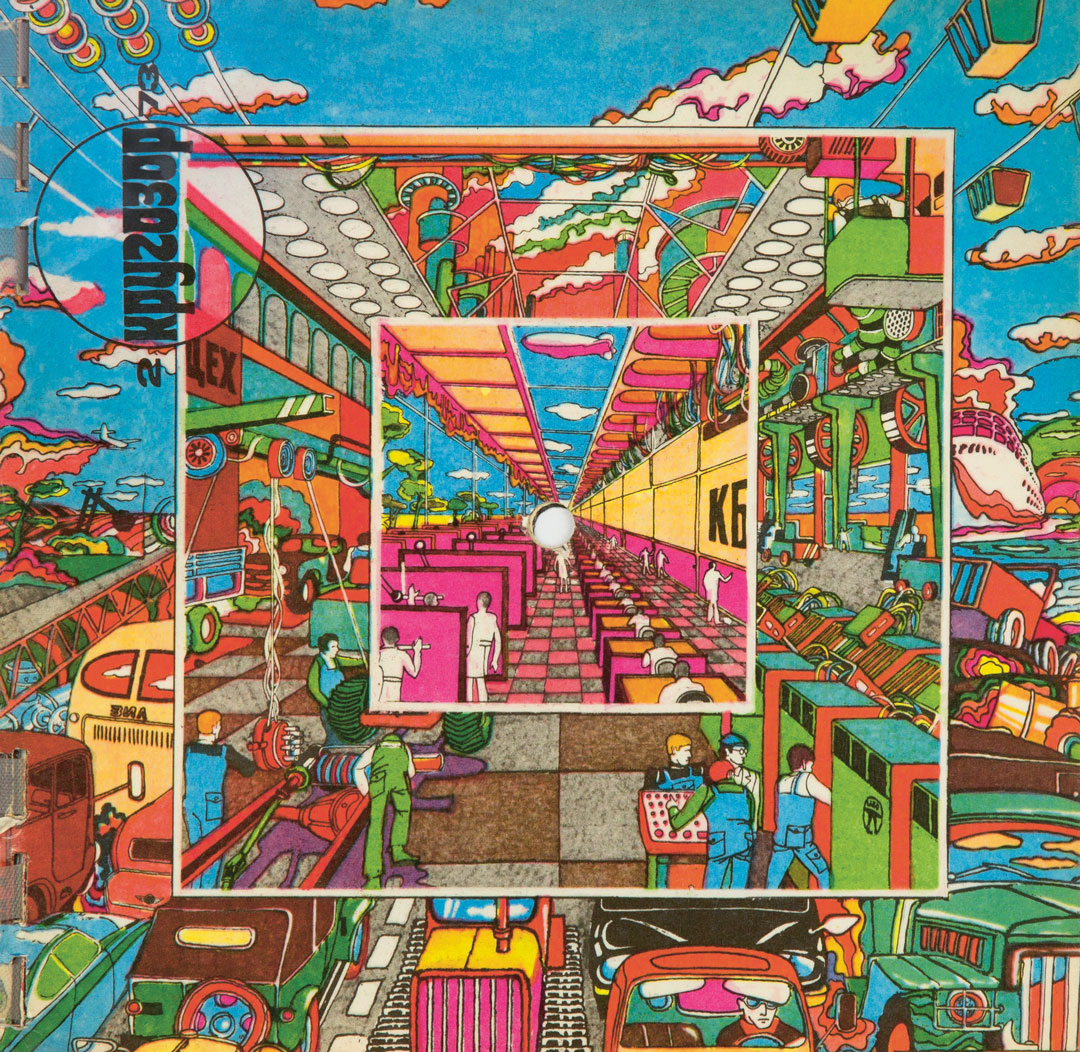

The love affair between the USSR and space science – presented as fiction and non-fiction – did not end with Tsiolkovsky. “In the Soviet Union, in particular during the Cold War , this effort manifested itself most prominently in a wealth of popular-science magazines used by the state to catalyze public engagement,” writes Sankova. “Deliberately aimed at all sectors of society, from children to adults, amateurs to professionals, the magazines contained all manner of scientific and cultural content: articles, statements and commentaries on recent national achievements, as well as literary and art reviews, and the latest science-fiction stories.”

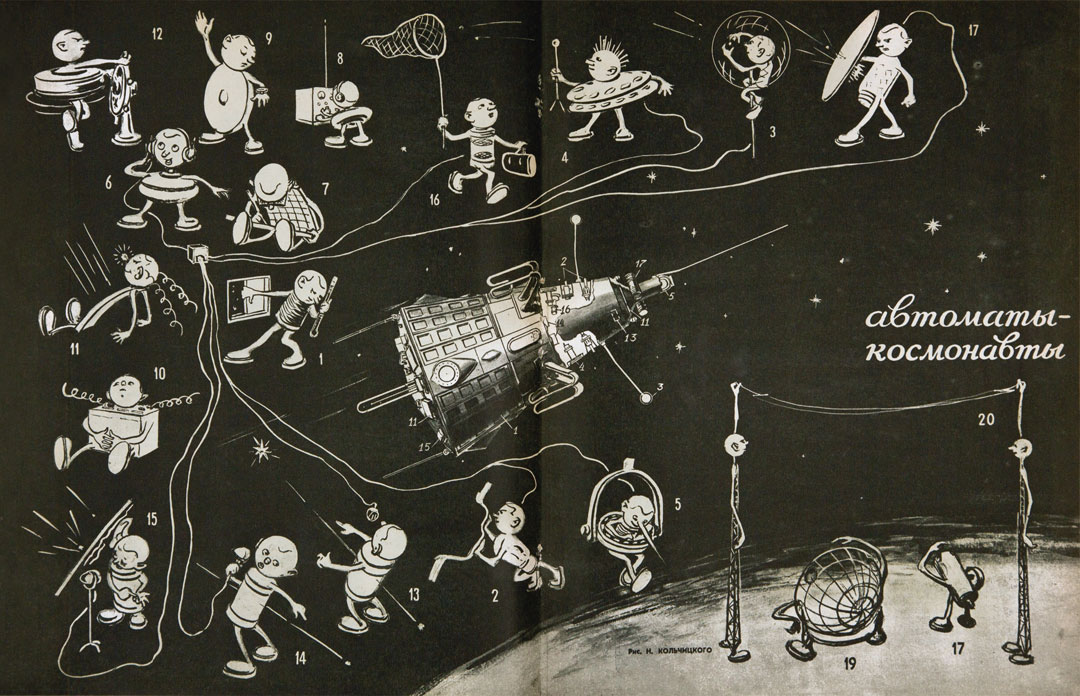

Soviet Space Graphics brings together some of the finest visual treatments from this era. The book includes playful children’s illustrations such as Machines – Astronauts, illustration by N. Kolchitsky, published in Technology for the Youth, issue 8, back in 1958, and showing the individual components of Sputnik 3 as different comic-like characters.

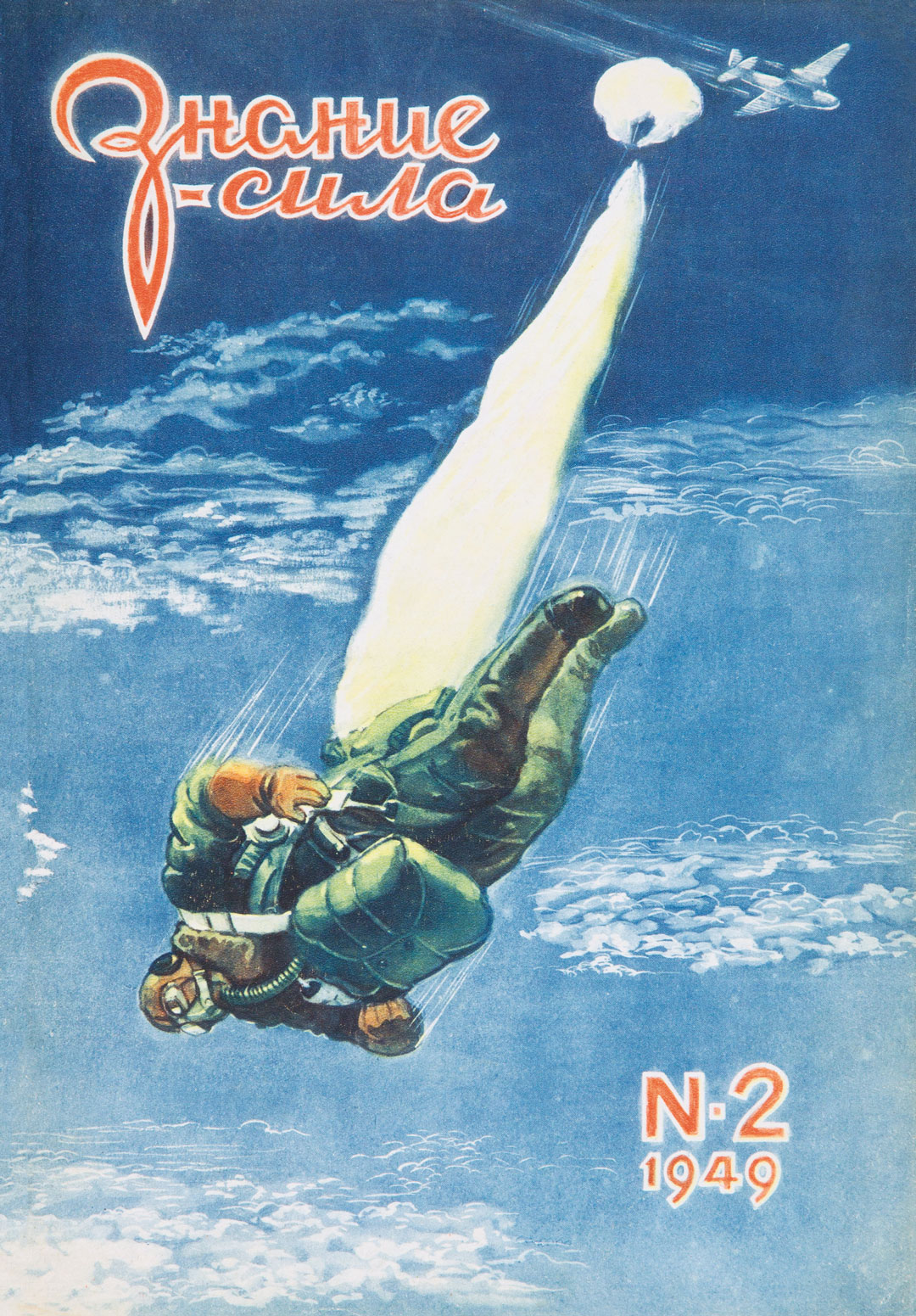

There are documentary illustrations, including a drawing by K. Artseulov of the skydiver Vasily Romanyuk, the first person to complete a parachute jump from the Earth’s stratosphere, at a height of 13,000 metres (42,650 feet); and, in one rare instance, works actually created by a cosmonaut; Soviet Space Graphics includes illustrations by Alexei Leonov, the first person to exit a spacecraft and ‘walk’ in space during the Soviets’ Voskhod 2 mission, and also the first individual to create a piece of art while in space; Leonov sketched the sunrise over earth from Voskhod 2, and went on to create many space themed illustrations, often working alongside fellow science-fiction artist Andrei Sokolov.

Plenty of the works in the book are best described as speculative, picturing moon bases or photon-driven rockets. Some of the pictures offer space-age views of earthbound subjects, like flying cars, telepathy machines and nuclear-powered airliners.

Others shade into paranoia, such as A. Shpir’s illustration for Knowledge is Power, issue 2, from 1950, which is inspired by Valentin Ivanov’s novel Energy Controlled By Us, “in which American imperialists and fascist military outlaws conspire to destroy the USSR using the Moon as a giant ‘death ray’ reflector,” explains our new book.

Of course, few of these future visions came to pass. Yet while the book tells us little about the future, it reveals a great deal about the past.

Fans of 20th century art and illustration will delight in the book’s poppy graphics that bring to mind plenty of Western practitioners, from Archigram to Hergé, Rube Goldberg to Diego Rivera. Those who grew up during the Space Race will enjoy seeing the kind of fantastical illustrations – familiar, yet strange – offered to children on the other side of the Iron Curtain. Readers with an interest in popular history will like this fun, illustrated guide to this progressive, futuristic, yet strangely antique period.

And anyone who has reveled in Star Wars, Star Trek, 2001: A Space Odyssey, or stared up at the night sky and wondered what venturing out into this final frontier might entail, will take delight in these works by fellow dreamers, looking into the stars in a different part of the world. Share in it all by buying a copy of Soviet Space Graphics here.