Both sides of Bertoia

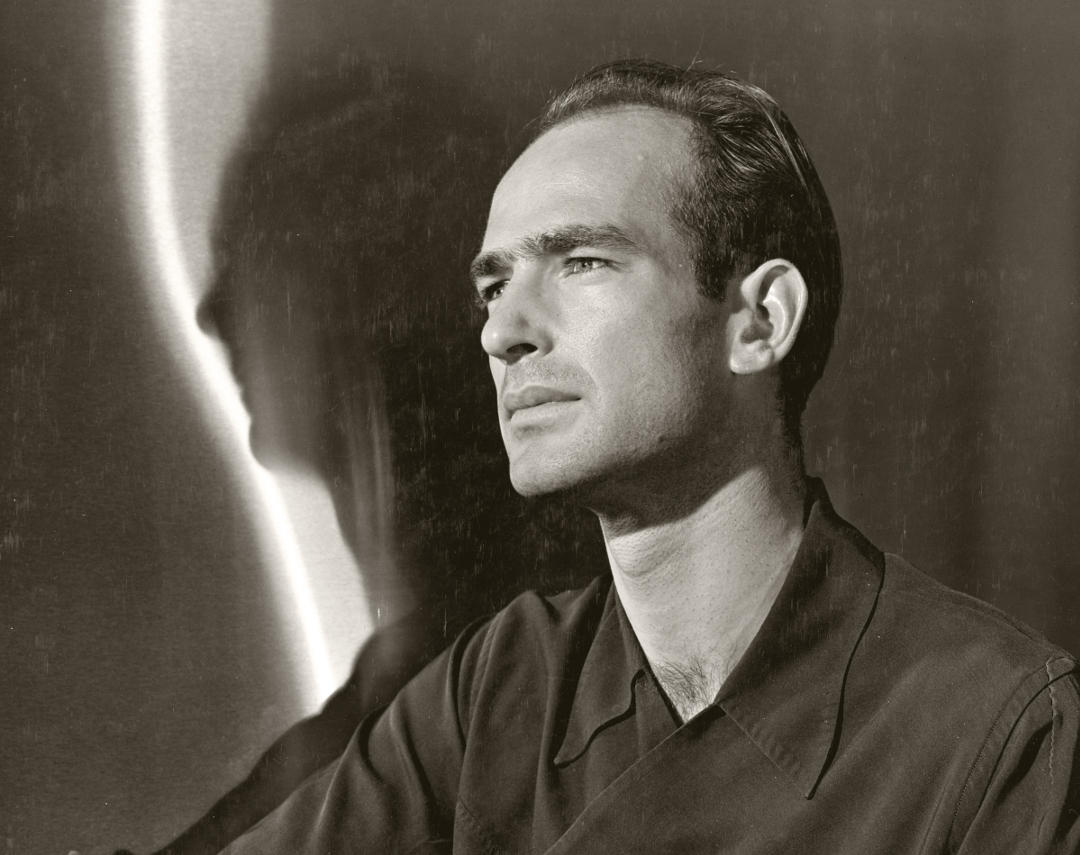

To celebrate his birth anniversary on Sunday we look at how America and Italy shaped Knoll designer Harry

The designer we know as Harry Bertoia was actually born with the given name Arri Bertoia, on 10 March 1915, in the tiny agricultural village of San Lorenzo d’Arzène, in Friuli, which Bertoia described as “somewhere between the Alps and Venice.”

Back then “a village childhood was more similar to one a hundred years earlier than to childhood there today,” writes Beverly H. Twitchell in Bertoia: The Metal Worker.

“Electricity and automobiles existed in cities but not in a village of 500 people. San Lorenzo’s size and location determined much of the character of life there; people farmed on a small scale, tending some livestock, growing corn, and cultivating their vineyards to produce wine.”

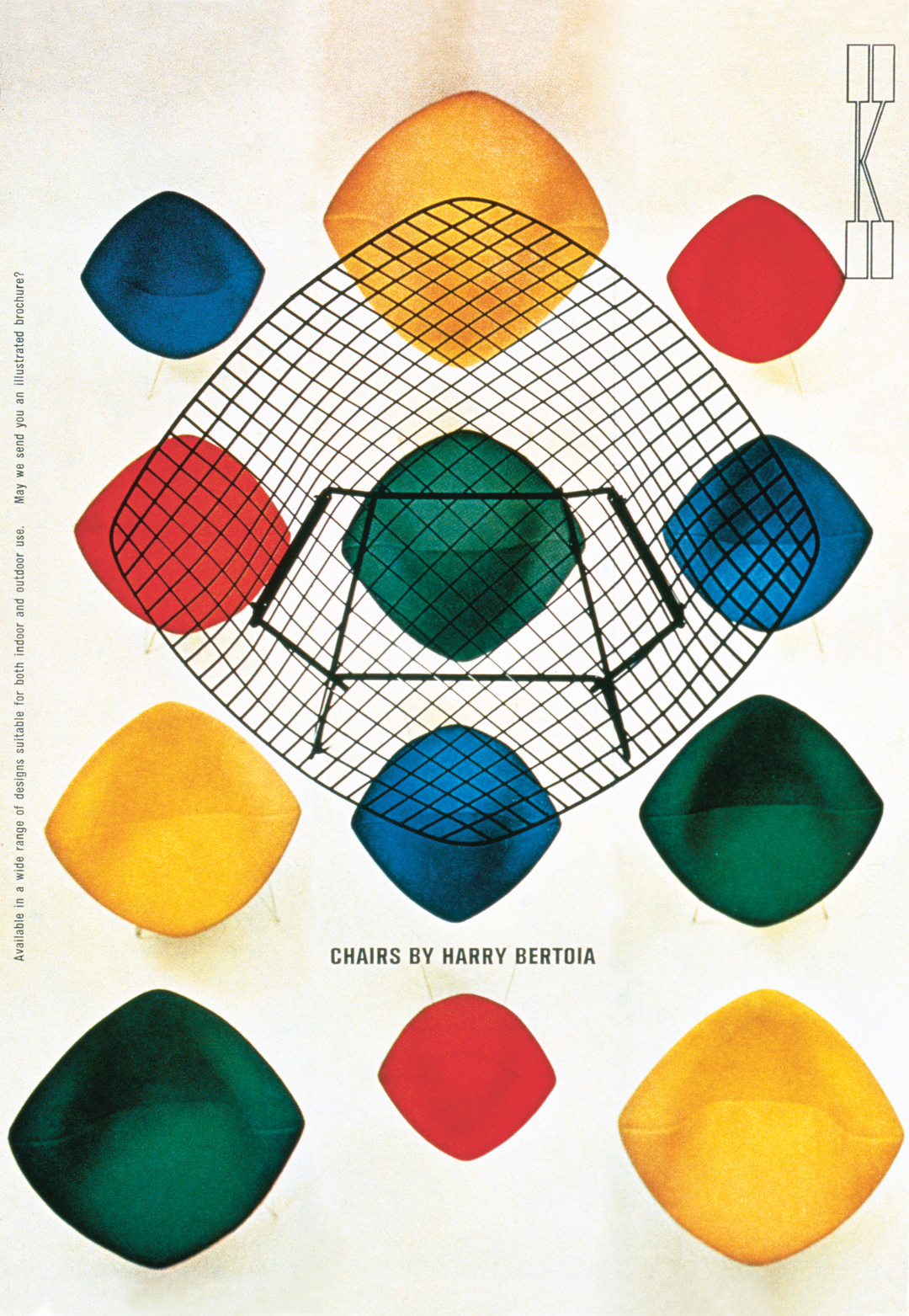

It seems a world apart from the flowing,grid-like perfection epitomised by Bertoia’s most famous creation, the Diamond chair, created for Knoll in 1952. Yet, despite coming to America as a young man in 1930 (he crossed illegally into Detroit from Canada) Bertoia’s Italian roots and early childhood would inspire the designer, artist and metal worker throughout his life.

“The sky is very blue in San Lorenzo,” Twitchell quotes him. “The earth itself is an inspiration to art.” When trying to account for his lifelong love of metalwork, he thought back to the gypsies who would come to his village, “the tinkers who made and repaired metal implements, beating tools, pots, and pans into shape and polishing them,” Twitchell writes.

Few works by him directly reference village life. Just two woodcuts, Winemakers and Corn Harvest, made while Bertoia was at Cranbrook Academy of Art in 1941, are, in Twitchell's estimation, “the only overtly Italian subjects in his vast oeuvre.” Nevertheless, his Italianate roots informed many other aspects of his long, and fruitful life in America.

“Like many who have had two countries, he often felt Italian when in the United States and, on his return to Italy, likely found himself to be very American,” writes Twitchell.

“Importantly however, belonging to the Italian tradition of several millennia of art and also being part of American Modernism were both essential to Bertoia’s sense of himself and his work. He always remained very Italian and simultaneously very American, having become comfortable in the dual existence that allowed him to love the old country and his new one.

"He was especially grateful for the opportunities the new country provided. The Italian countryside, where he played, did farm chores, explored nature, and grew, was essential to determining the person and artist he became. That landscape of his childhood shaped his love of the natural world and would be the basis of his art. He would come to appreciate that nature was not simply his surroundings but something of which we are all a part.”

The shaps of his tree-like sculptures clearly reflect this appreciation for organic forms. The fountains Bertoia would go on to create may well have been informed by those in his childhood home, Twitchell argues.

“Born in a tiny village in northern Italy, Bertoia understood that for thousands of years fountains have been centres of daily life in small towns and urban neighbourhoods,” writes Twitchell.

“Sources of water for residents, they were also gathering places where friends and neighbours chatted, joked, and gossiped while filling containers with water to take home.”

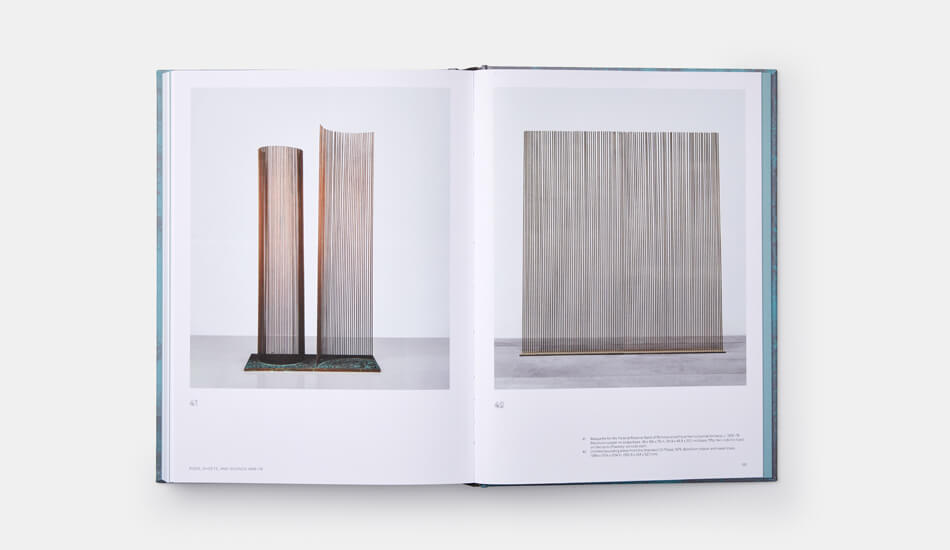

His later works, aural sculptures that produced his own, self-style “sonambient” music may owe some debt to his musical upbringing.

“Harry’s father and four uncles sang, accompanying themselves on string instruments and the accordion,” writes Twitchell. “Family lore maintains that Giuseppe’s father was first “violin cellist” at La Fenice, the opera house in Venice. Music was always important to family life as entertainment and relaxation.”

Twitchell even makes the case for viewing Bertoia’s work in light of later, Italian cultural developments.

“A number of Bertoia’s works suggest relationships to trends in art at that time, especially works of Italian Arte Povera,” writes Twitchell, “in which humble materials were used to express their own nature as well as the fragility of existence.”

Bertoia only returned to his mother country once, In 1957, yet his later life, from 1952 onwards, harked back to his childhood. Bertoia largely worked and lived on a farm in Pennsylvania near the Knoll offices. “Smaller and more isolated than the stone house where Bertoia was born, the residence must nevertheless have felt more familiar than any place he had lived since leaving San Lorenzo,” writes Twitchell.

20 to 30 yards from that house stood a barn, where Bertoia created sculptures, drew up graphics and made his acoustic work, a setting which reflects his origins and nascent inspirations.

“Bertoia found great pleasure and tranquillity in living in the quiet of a small Pennsylvania farm for the last thirty years of his life,” writes Twitchell. “The real origin of the works in Bertoia’s barn lay in another small farm, the one in rural Italy, where he was fascinated by weather, streams, the growth of plants and animals. His few surviving childhood drawings already had the careful observation, attention to detail, and craftsmanship that would characterize his life’s work.”

For more on Bertoia’s life, work and inspirations, order a copy of Bertoia: The Metal Worker here. And keep an eye on the instagram feeds of Knollinc and Wrightauction.