Phaidon's 15 Minute Art Lesson - Sex and the Viennese Secession – by Peter Vergo

Read how Klimt and Schiele, both of whom died in the Spanish Flu pandemic, shook up European art and sex

Sex was central to the Viennese Secession, the Austrian art movement which ran from the final years of the 1900s up until the end of the First World War and the subsequent Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918 – a disease which claimed the lives some of the Secession’s key figures. This rebel art movement, which broke away – or seceded – from traditional Viennese institutions in the late 19th century, marked out the divide in a city where some preferred to deny any hint of libido, while others could think of nothing else.

As author and art historian Peter Vergo writes in his book, Art in Vienna 1898-1918, one of the “outstanding preoccupations of fin-de-siècle Vienna, in literature and art as in life itself, was the whole subject of what [Vienna resident and Austrian father of psychoanalysis, Sigmund] Freud called the ‘misunderstood and much-maligned erotic.” Vergo goes on: “In an age which was, strictly, no longer one of belief, sexuality was regarded as much for pragmatic as for religious reasons as a disruptive and therefore dangerous element, the very existence of which was not simply denied but – even in scientific circles – scarcely mentioned.”

An outright denial of sexual urges was not a simple process in a city changing so quickly. “Vienna, the hub of a vast, multi-racial Empire, attracted to itself countless thousands of Czechs and Magyars, Bohemians and Slovenes – citizens of far-flung, even mutually hostile provinces who found themselves, at the same time, united in an uneasy alliance under the ancient crown of the [Austrian Royal family, the] Habsburgs,” writes Vergo.

This divided city – which, on one hand was in part, traditional, patrician and staid, and on the other vibrant, lively and culturally diverse – is best summed up by the Austrian writer of that time, Otto Friedländer. Vergo quotes Friedländer as saying: “Vienna in the first decade of the century is one of the intellectual centres of the world, and she herself has no idea … Two or three thousand people write words and think thoughts which will overturn the world of the next generation – Vienna is oblivious. A tiny circle of men: writers, politicians, academics, journalists, artists and civil servants, lawyers and doctors, preoccupied with the problems of the day, whose thoughts will determine the future of civilization. They are an island. No bridge unites them with the Viennese themselves. Only a small number of disciples – not schools –follow in their footsteps. The slumbering city vegetates in its own happy mediocrity and does not dream what great things are being thought and created in her midst.”

Vergo is clear on the sexual hypocrisy of Vienna’s sleepy establishment. He writes that, “for while no school teacher, no textbook would ever mention subjects such as prostitution or sexual hygiene, it was at least tacitly assumed that the male offspring of respectable houses would, at one time or another, sow their wild oats, that the natural urges of male youth would find their inevitable object in the countless ‘ladies of pleasure’ who, under police surveillance, haunted well-defined areas of the old city, or in the erotic clubs and cabarets which carried on a clandestine existence behind the ‘faultless, radiant facade’ of the capital.

“That women, on the other hand, should be moved by the same urges, even the same need for physical affection, offended against the notion of the sanctity of woman. Thus, the daughters of well-to-do families were brought up in the sterilized atmosphere of convent schools and governesses, every book discreetly vetted, every outing chaperoned.”

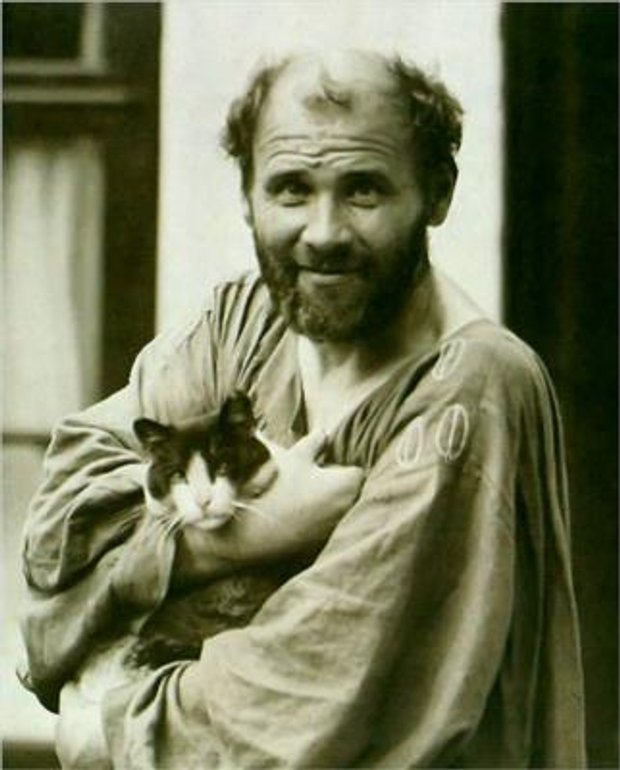

The great artists of the Viennese Secession such as Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele not only expressed erotic desires, but also captured something of the city’s difficulties when it came to sex.

Vergo examines Klimt’s 1912-13 work, The Virgin, “in which the central figure is again shielded from the viewer’s profane gaze by a layer of ornament.” He states: “Her companions, on the other hand, are half-naked; although these female figures appear to have positioned themselves in a watchful circle around the virgin, as if guarding against any possibility of male intrusion, their own partly exposed bodies and lascivious glances have been seen as evoking ‘yearning desire, absolute surrender and the sweetest form of languor'. But if the unspoken agenda that lies behind this intricate composition has to do with woman’s fear of and, at the same time, desire for the male and for sexual fulfilment, Klimt’s painting offers us the possibility of such an interpretation only in the subtlest of ways.”

Schiele, a protégé of Klimt’s, and 28 years his junior, dug into deeper desires, some of which we find difficult to come to terms with today. The artist may have worked from medical photography, perhaps supplied by his friend, the gynecologist Dr Erwin von Graff; he also used his younger sister Gerti Schiele, as a model. "As a young adolescent, Gerti repeatedly posed nude for her domineering brother, who would sometimes appear at her bedside, stopwatch in hand, goading her to get up in time for an early-morning modelling session,” writes Vergo.

Schiele was quite aware of the baser appeal of some of his work. Vergo notes that the artist, “at times made a living from the sale of his more explicit drawings. There were even plans to publish a folder of erotic subjects by him in a limited edition of one hundred copies, but nothing came of this project.”

More troublingly, Schiele also used nude children as models. "To what extent his interest in his younger models was anything other than purely artistic will probably never be answered; once, when reproached with the eroticism of his drawings, he replied with some bitterness: ‘I certainly didn’t feel erotic when I made them!’”

This, fairly weak defence, did not prevent Schiele from being arrested on the charge of seducing a minor, - “there was almost certainly no foundation in the charge, and he was eventually acquitted” writes Vergo - as well as sentenced for disseminating indecent drawings.

The artist spent 24 days in prison during the spring of 1912, “an experience that left an indelible scar on his consciousness,” Vergo says, quoting from one of Schiele’s letters, in which he wrote, “‘I am wretched, I tell you, I am inwardly so wretched.’”

Klimt, by comparison, took any public criticism of his work with greater grace. Vergo quotes the Austrian writer Bertha Zuckerkandl's tale of the artist’s reaction to be being called a pornographer in a 1907 newspaper review of his exhibition at the Miethke Gallery

"It was not yet midday when, without any previous arrangement, the closest members of Klimt’s circle of friends came one after another and knocked on the firmly locked door of the studio in the Josefstädterstrasse,” Zuckerkandl wrote. “The same question was in everyone’s mind: what did Klimt intend to do now? One friend gave voice to all our thoughts: ‘You must sue for libel’. And a well-known defence lawyer, who happened to be present, gave his opinion as follows: ‘There’s no judge and no jury who, confronted with this libel, could fail to decide in your favour’.

“Klimt had been listening quietly, still working away at his easel. ‘Herr Doktor’, he now asked, ‘how long would an action of this kind last?’. ‘About two days’, came the answer. ‘But children’, cried Klimt, ‘I could spend those two days painting!’ And that was an end of the matter.”

It was, on reflection, a wise choice. Klimt and Schiele died a little over eleven years later, both victims of the 1918 Spanish Flu. Yet their sexually charged works live on in the eyes and minds of gallery goers and art lovers across the world, many of whom are, perhaps, a little better equipped to enjoy the pleasures of the flesh, when compared with the staid Viennese establishment of the early 20th century.

For more from Vergo on this dizzying period of art history, get a copy of Art in Vienna 1898-1918 here.