Stories from the Secession - Radical music and art

The Viennese Secessionist artists didn't just limit their influence to painting, as Art In Vienna explains

The lush, golden canvasses of the Viennese Secession are known and loved throughout the world. Yet it might surprise some of their admirers to learn that music was almost as important as visual arts in the minds of those radical Austrian artists; perhaps not so surprising, given that the city also gave the world Beethoven and Mozart. Although the Viennese Secessionists worked in art and applied architecture, they had a very strong kinship with the music of their day, and the great masters who still cast a cultural shadow.

Beethoven was a touchstone - Gustav Klimt exhibited his Beethoven Frieze in 1902, at the fourteenth Secessionist exhibition which also featured German artist Max Klinger’s monumental statue of the composer. Ver Sacrum, the official magazine of the Secession, featured numerous contributions in the form of sheet music from composers such as d’Albert and Hugo Wolf. Arnold Schoenberg mixed with young Secessionists such as Oskar Kokoschka at Vienna’s Café Central, and had his portrait painted by Richard Gerstl. He recognised kindred spirits, as did Richard Strauss, who found in Klimt’s Judith II echoes of the soundworld he had created in his opera Salome.

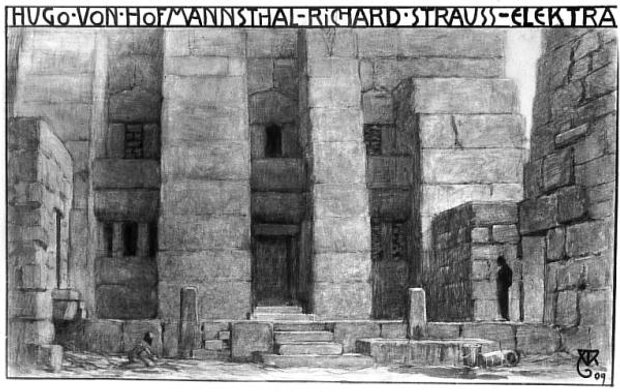

The Secessionists were inspired by Richard Wagner’s idea of the Gesamtkunstwerk - the total work of art of which he dreamed in which all the disciplines were fused in an audiovisual whole. These inspired Alfred Roller to produce a series of intensely colourised stage and costume designs for Wagner’s opera Tristran And Isolde, which so impressed Gustav Mahler that he appointed him Head of Design at the Imperial Opera. There, Roller produced sets for works by Strauss, Carl Maria Von Weber as well as further Wagner operas such as Parsifal and The Flying Dutchman.

Sadly, the Secessionist’s enthusiasm for new music was not shared by either the establishment or the Viennese public who almost relished their hounding of the avant garde. Vergo relates how Mahler once intervened during a Schoenberg performance to tell an audience member to stop hissing, only for the heckler to reply, “I hiss during your symphonies too!”

Peter Vergo’s Art In Vienna 1898-1918 is a brilliant, comprehensive account of one of the great art movements of the early 20th century, an era in which the radical idealism of young artists was pitted against the overbearing conservatism of their elders, who preferred to stew in old historical certainties rather than embrace modernity. You can read another of our stories from it, about how Vienna came to lead the artworld here. Look out for our next story from the Secession soon, and for a richer understanding of the time buy a copy of Art in Vienna 1898 – 1918 here.