Remembering Carolee Schneemann, the artist who took on Greek myths and macho Ab-Ex painters

Schneemann, who died yesterday, managed to link mid-century US painting with sex, magic and ancient myth

From Queen Boudica to The Witches of Eastwick, wild, sexy, powerful women are familiar figures in the popular imagination. Carolee Schneemann, the American artist who died yesterday at the age of 79, could be counted among that number. “An early pioneer of body-based performance art, Schneemann is celebrated as a seminal, trail-blazing feminist artist,” explains the text in our book Flying too Close to the Sun: Myths in Art from Classical to Contemporary.

Born in Pennsylvania in 1939, Schneemann came of age at a time when the dominant form of art was macho Abstract Expressionist painting, and much of her provocative work was staged in response to the manly drips and splashes of Pollock, de Kooning and co.

"Feminist art practice emerged in the same period of ferment as second-generation feminism and feminist art history, in which then dominant modes of Modernism, especially Abstract Expressionism, were seen as the culmination of centuries of neglect, disavowal or exclusion of female artists from the art historical canon," the editors write.

"Painting was often regarded as the preserve of men, whereas the emerging discipline of performance, and particularly those who used the naked body, were free from such onerous and repressive traditions."

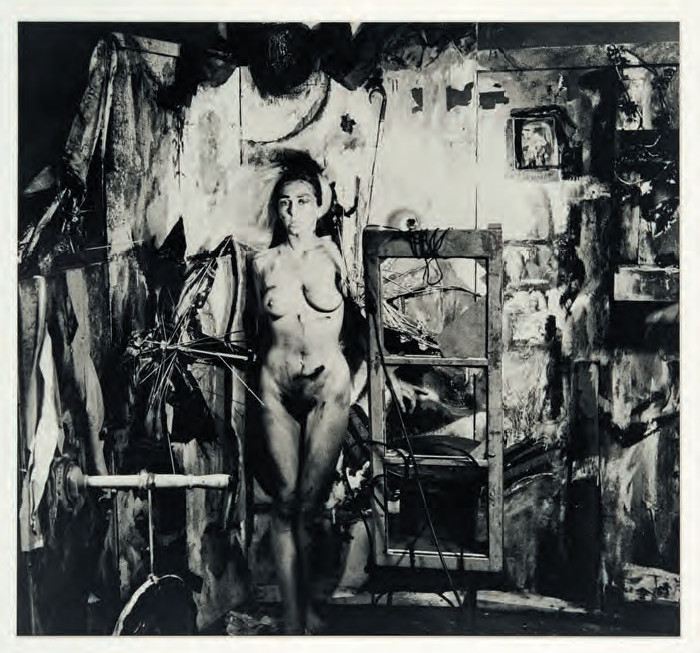

Bear this in mind, and it’s clear how her early, 1963 work Eye Body (pictured here and featured in our book) could be seen as a visceral response to the prejudices in modern art.

"Eye Body was a private action staged in the artist’s studio without an audience and exists solely in photographic form. The artist wanted to combine her physical, naked presence with the materials of the artistic environment in which she produced paintings and constructions – paint, chalk, grease – so that the female body became simultaneously the active seeing subject and object."

However, our book also draws parallels between Schneemann’s work and early cultural developments. In Greek myth Medea was a barbarian princess who betrays her people to help Jason and the Argonauts claim the Golden Fleece. When, after numerous acts of guile and barbarism, Medea herself is betrayed, she kills Jason's wife and her own children, before escaping without punishment to Athens.

This classical myth, dramatised by the Greek playwright Euripides could be seen as a misogynistic depiction of murderous, untrustworthy, witch-like women. Nevertheless, some have offered a feminist reading of Medea, presenting her as a powerful woman, debasing herself to fight for what is rightfully hers.

In this way, we can draw parallels between this pre-Christian figure, and American artist Carolee Schneemann's early, barbaric body art.

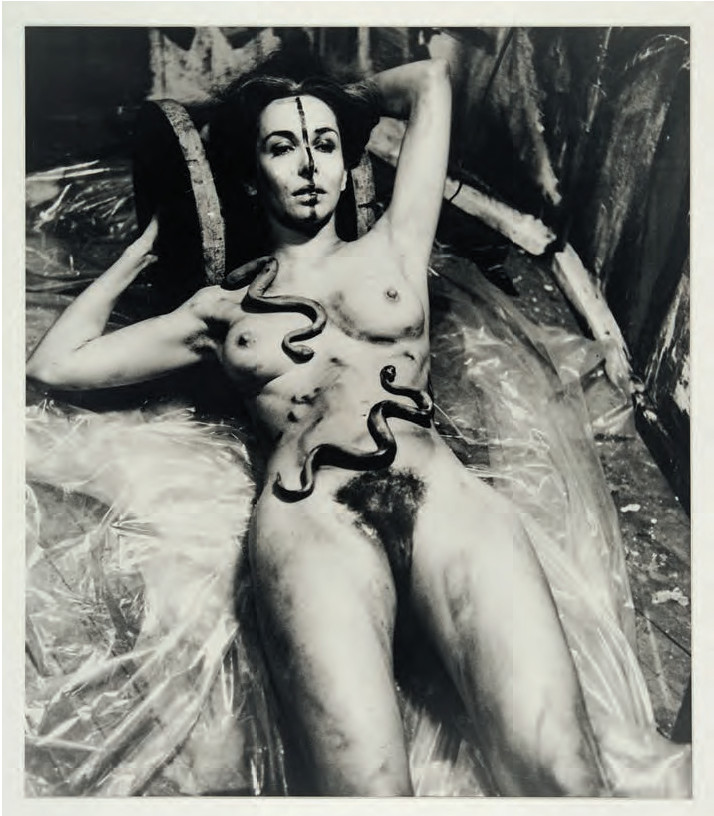

The book makes clear that Schneemann's immediate oppressors weren't Greek warriors, but macho painters. Yet Schneemann's primitive Eye Body performance, in which she covered her naked body with paint, glue, fur, feathers, garden snakes, glass, and plastic, can be seen as Medea-like in its spooky primitivism, and its attempt to wrest control.

The artist describes her body in these shocking works as being "written over in a text of stroke and gesture discovered by my creative female will." Viewers can see both the barbaric spectacle and appreciate the power the artist wields, in a world otherwise dominated by men.

"A reflection of the myth of Medea might be usefully related through the notion of archetypes and an activist agenda," explains our book, "the denouncement of women as witches throughout history is a frequently cited example of the perceived danger of female agency in feminist theory, while the feminist assault on the patriarchy can be seen as a latter-day parallel to the fury of Medea scorned."