The art Ed Ruscha made with his pop star friend

A new exhibition explores a little-known collaborative relationship predating Ed Ruscha’s arrival in LA

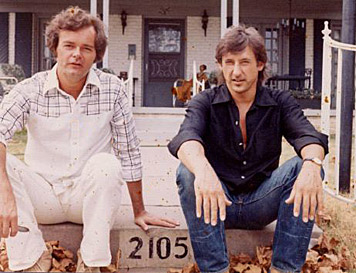

In 1956 two teenage boys drove 1,327 miles from their home in Oklahoma City to Los Angeles. The pair, who had known each other since their school days and had lived only a few blocks apart, were heading off together to the West Coast, one to attend art college, the other with rather less well-formed plans.

Over the intervening decades the art school pupil, painter Ed Ruscha, has done more to shape the look of LA in the public’s imagination than perhaps any other artist working today. However, his travelling companion, writer and musician Mason Williams found equal success in LA’s entertainment industry, as a musician, and a comedy writer.

In the late 1960s Williams composed both the theme music The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour, and served as head writer on the show. He went on to work on Saturday Night Live, have hits with his instrumental single, Classical Gas, and as the co-writer of the 1968 novelty hit Cinderella Rockefella. Music and comedy aside, Williams also wrote poetry, published books and created pop artworks which were very much in keeping with the kind of work Ruscha himself was producing at the time.

Unsurprisingly, the pair collaborated quite a bit over the years, and the fruits of these collaborations are on show this month in New York. The Alden Projects gallery is showing Double Standard: Ed Ruscha & Mason Williams 1956 – 1971 (Part 1) a retrospective that looks into “the early dialogues, collaborations, and elective affinities between Ruscha and Williams.”

The friends produced daffy, little-known art books like the 1969 edition, How to Derive Maximum Enjoyment from Crackers, and the 1967 publication Royal Road Test, which documented the resultant effects of throwing Royal typewriter out the window of a speeding car on a desert highway; Ruscha was “the driver,” and Williams “the thrower”.

There are also some more thoughtful, though equally Dada-ish projects, including 1967’s the Night I Lost My Baby a photo and text narrative about a lost girlfriend in Las Vegas, wherein the arrangement of the photos was determined by a throw of dice.

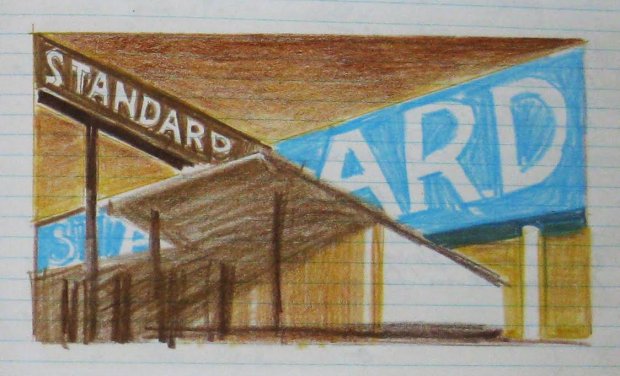

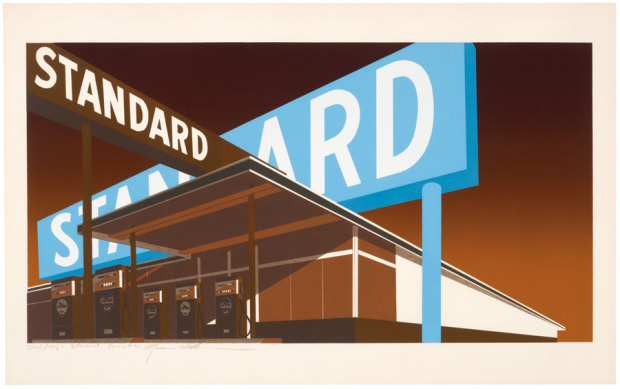

However, they also produced some more iconic works such as Ruscha’s iconic Double Standard print from 1969 which, the gallery explains, was actually a collaboration between the two artists.

Alongside these joint efforts, there are also a few solo works by Williams in the show, including his life-sized print of a Greyhound bus, as well as previously unseen photographs documenting Sunflower, Williams’ attempt to draw a record-breaking, huge flower in the California sky using skywriting planes.

"In 1967,” Williams recalls, "I had an idea for a film: to draw the world's biggest sunflower. The film was to be a slow-motion aerial ballet in which an old bi-wing aeroplane skywrite “draws” the stem and leaves of a flower in the sky beneath the sun, the sun itself thereby becoming the blossom of a ‘Sun’ flower.

Like many high-minded concepts conceived during California’s Summer of Love, the film was never quite realised, yet the pictures, alongside the other works, serve as an enlightening look into the a little-known creative relationship that spanned both the gallery system and the wider entertainment business, as well as an apt reminder of the time when those within the avant-garde and primetime media really didn’t think in such different ways.

For more on the show go here; for more on Ed Ruscha take a look at our books, and for greater insight into this period consider our Pop books.