Catherine Opie and Friends

Can the fine art photographer’s dignified images of her friends help people become more empathetic?

Back in the late Eighties, if you wanted to meet Catherine Opie, all you had to do was head to her local camera shop. “By 1989 I was a rental manager at Pan Pacific Camera on La Brea [in Los Angeles],” the fine art photographer explains in her new book, the first survey of the work of one of America's foremost contemporary photographers. “I would set up the equipment for Herb Ritts and Annie Leibovitz and all of these photographers’ commercial shoots.”

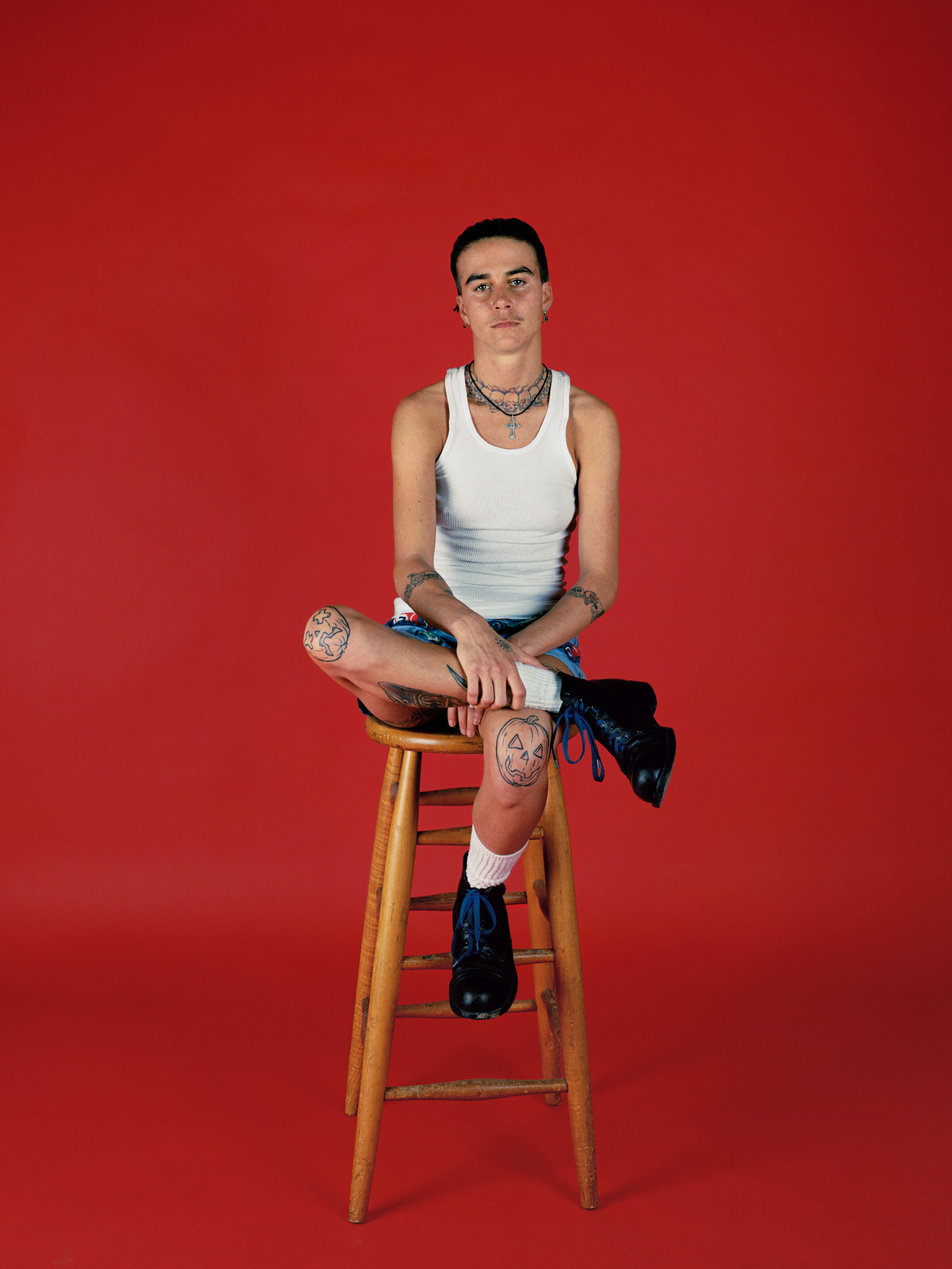

The job gave Opie access to a huge amount of high-quality camera gear. All she now needed was a subject, and she solved that final problem in an equally cost-effective manner. “I had my friends come over for a weekend and gave them all $10 to buy a moustache,” she says.

Taking pictures of your pals is something more or less all of us do these days. However, Opie elevated this quotidian task to high art, as the writer, curator and executive director of the Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, Elizabeth A. T. Smith, explains in our new book.

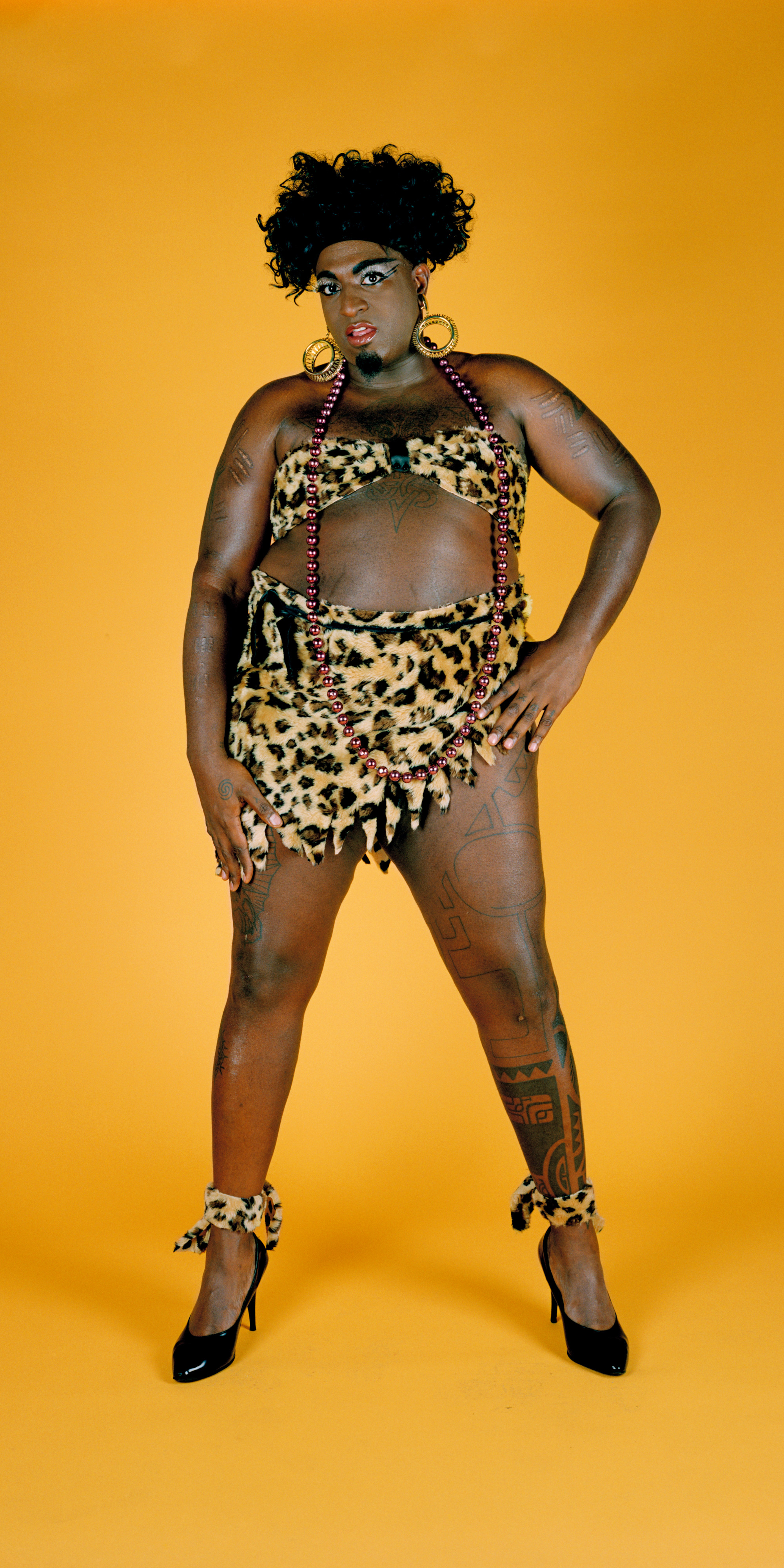

“The sitters in Opie’s early portraits were members of her own ‘family’ of close friends, those with whom she felt at home,” writes Smith. “ While the space of home is not visualized explicitly in these images, Opie’s focus on the architecture of bodies that are stylized, embellished, and adorned reveals their identities as part of a community of shared interest.”

Opie herself echoes these sentiments in the book’s Q&A section. The artist tells the curator and writer Charlotte Cotton how her college friend, the painter Richard Hawkins, helped her push her work forward.

“Richard helped me understand that if I wanted to talk about the architecture of the body from within my own community, I needed to have the body out of its environment,” she says.

It was a smart piece of advice. In these pictures, Opie creates, “dignified, elegant, and highly aestheticized images of those who were often dismissed or considered ‘perverts’ by the larger society and by others in the gay and lesbian communities who were seeking acceptance in the mainstream,” Smith asserts.

Since those early days, Opie has widened her circle, shooting famous artists such as John Baldessari and Matthew Barney, a series of children, including many photographs of her own son, Oliver, as well as a dedicated series of football players and surfers.

Yet it's Opie’s friends, some of whom she’s photographed multiple times over the years, that truly fulfill her photographic role.

As Opie sees it, a photograph “bears witness in a specific time,” she explains. “And in order to traverse my way through it, there has to be a personal connection to the questions of how we operate as a society and as a community. Is there no other way for me to get into a better place of humanity? If I image it, and image it, and image it, somehow, within that library, within that archive, am I punching any holes at all in the way that people can become more empathetic?”

To see more of those beautifully empathetic images, order a copy of our Catherine Opie book here.