African Artists and the photo studio

The enduring influence of posed, studio portraits can be seen in our groundbreaking new book on African art

If you think you’ve seen it all, you really need to take a look at African Artists from 1882 to Now. Even the most dedicated of gallery goers will find something new to engage with and love in this beautiful new book profiling 300 modern and contemporary artists born or raised in the African continent.

You’ll find traditional paintings and sculptures, as well as video works, installations, mixed-media pieces, collages, performances and more; you can pick out the influence of prevailing art world trends such as minimalism and cubism; and you’ll also learn a little about the wider forces that shape artists in this continent.

One key influence is the commercial photo studios that thrived in West Africa during the late 20th century. In a way, these places weren’t so very different from photo studios in the West, where people once went to get their picture taken. However, the aesthetics, aspirations and imagery are quite different.

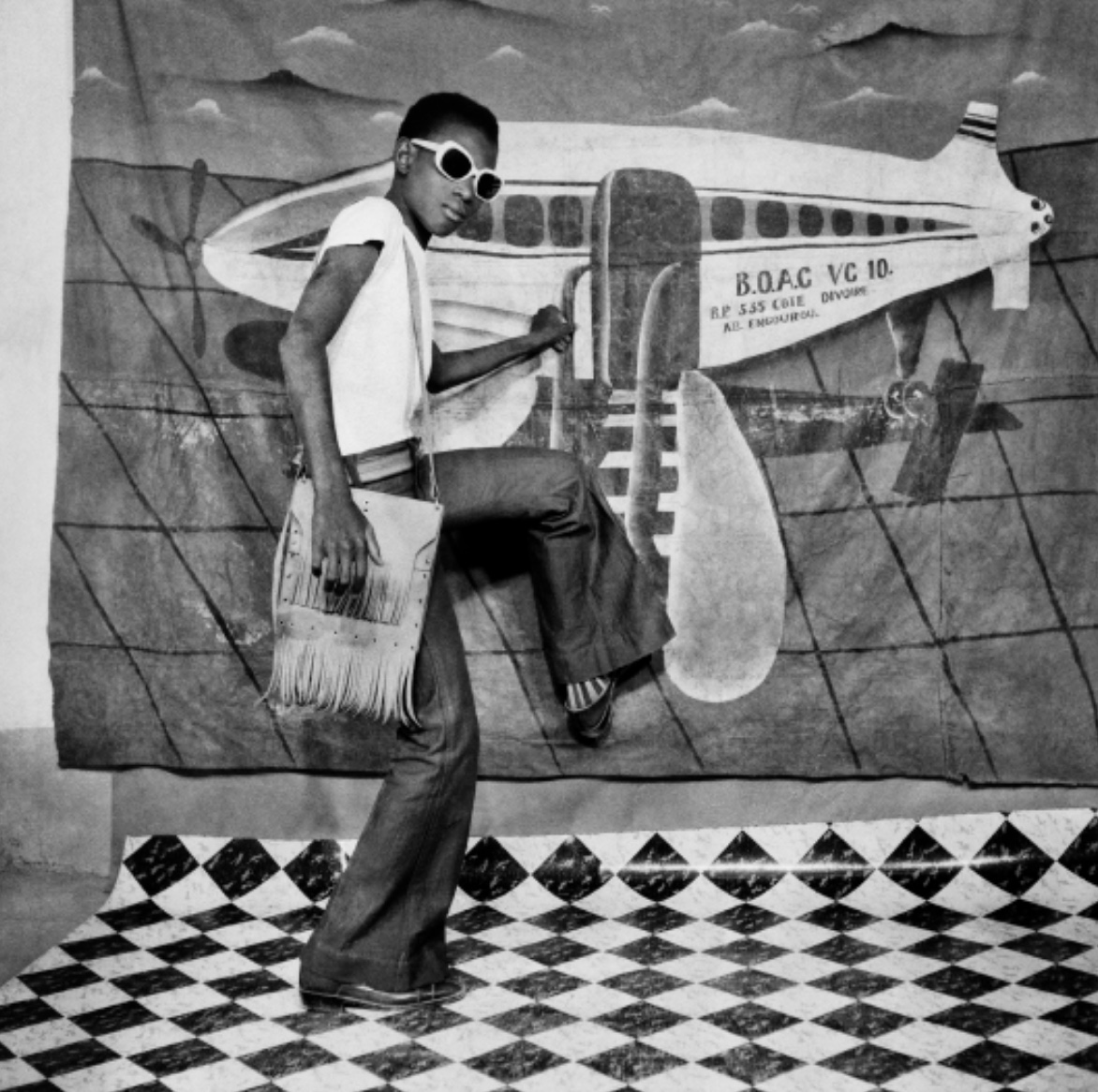

Consider Burkina Faso photographer Sory Sanlé’s images (top). “Beginning his career as a photographer’s apprentice, Sanlé opened his famed photography studio, Volta Photo, in 1960, the same year of Burkina Faso’s liberation from French colonial rule,” explains our book. “People from across the region visited Sanlé’s studio, where music played and customers fashioned themselves partaking in leisure activities of modern life, with an extensive range of props and painted backdrops to choose from. This photograph [top] features one of Sanlé’s most popular backdrops depicting an airplane ready for take-off, its subject full of expectant possibility. Capturing the disjuncture between aspiration and reality, his set-ups – long before digital photography and the advent of selfies – offered an escapist fantasy where people became the stars of their own dreams.”

The Ghanaian photographer Philip Kwame Apagya, practicing a few years later, deals with similar issues. “The son of a photographer, Apagya learned his trade in his father’s studio before going on to study photojournalism,” explains our new book. “His photographs are rooted in the lineage of West African studio portraiture, using painted backdrops to transport his subjects into imagined worlds that exemplify western consumerist ideals of luxury. His sitters choose their fantasy environment; they are depicted cheerfully boarding an airplane, in front of an affluent home or within a modern urban interior. Apagya repaints his backdrops regularly to keep up with clients’ demands. ‘Truth is not my major concern,’ he has said. ‘I am more interested in creating prestige, fantasy and beauty.’ In this photograph the branded hi-fi, television and video, together with the opulent curtains and padded sofa, signify material success. The illusion of the scene is broken by the visible studio wall and the change in perspective where the floor meets the backdrop – however, Apagya’s illusion is not meant to fool anyone.”

Finally, the young Ethiopian artist Atong Atem comes from East Africa and now resides in Australia, but she also draws on the work of West African photographers (in particular, the Malian studio photographers such as Malick Sidibé and Seydou Keïta) in her work, which explores social and cultural identities among African diasporic communities down under.

“Her self-portraits incorporate elements of fantasy, surrealism and science fiction to further address the politics of looking and being looked at,” explains our book. “In each one she radically changes her appearance, painting her face in elaborate ways with bold colours and patterns. Weary of always being preceded by her ethnicity, she began the series to address the sense of alienation she felt growing up in a white-majority society, and to contribute to ongoing conversations about colonialism, in Australia and globally."

Want to know more about African artists and how they impacted the broader sweep of art history? Then order a copy of African Artists here.