African Artists and sexuality

Pioneering Queer artists are among those offering insights into contemporary life in the African continent in our groundbreaking new book

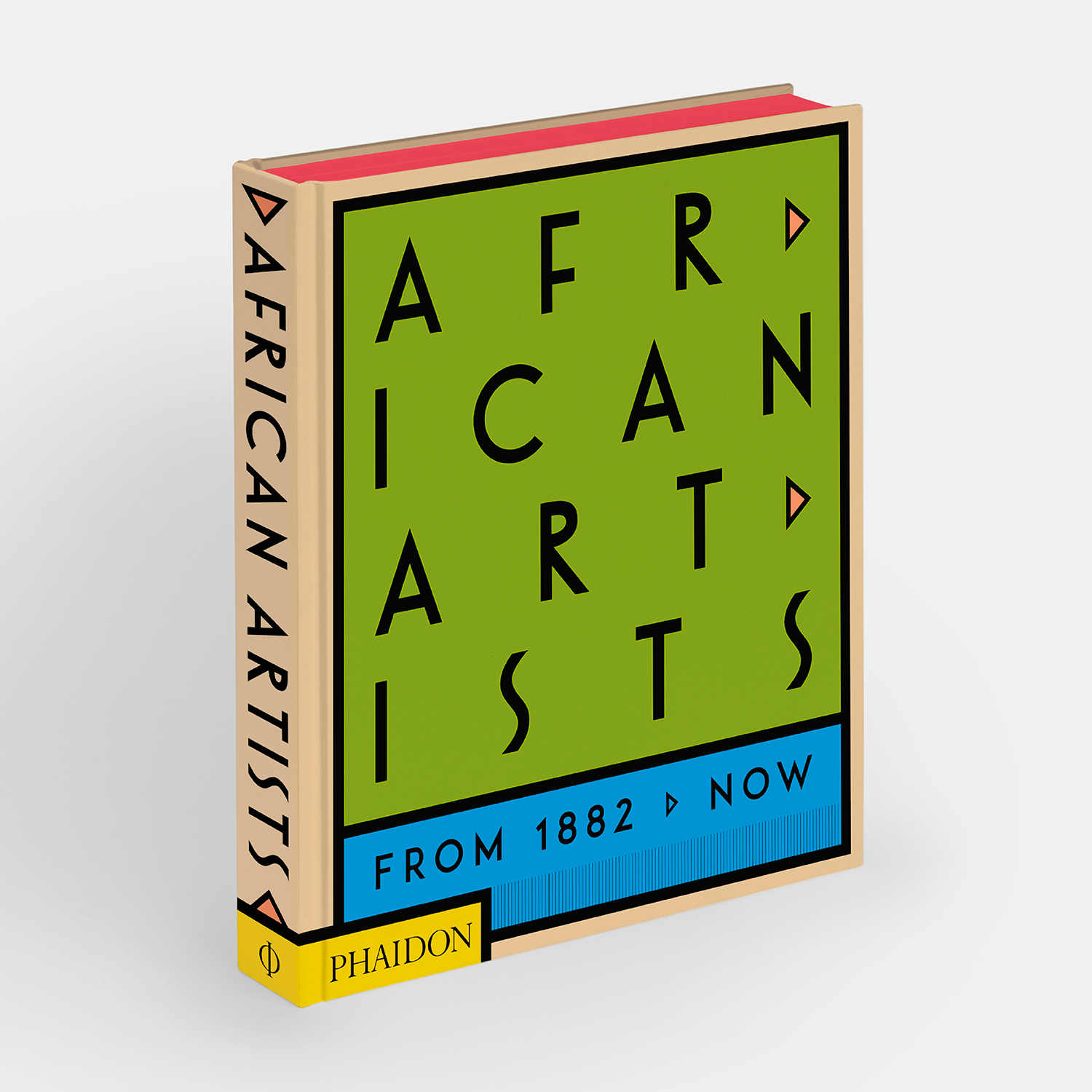

African Artists from 1882 to Now is as diverse a survey of artworks as you could hope to come across. This beautiful new book features the work of over 300 modern and contemporary artists born or raised in the African continent. Within this selection there are conventional portraits and sculptures, as well as modernist-style abstract works, documentary photographs and records of a wide array of performances, video works and installations.

The subject matter and points of view expressed are broad too, especially in the book’s more recent inclusions. As the historian, curator and artist Chika Okeke-Agulu puts it in his introduction to our new book, “contemporary artists, distanced as they are from the experience of colonialism, adopt a diverse range of critical positions on tradition and heritage, socio-economic formations and structures, and political and ideological affiliations.”

In among all this is a fair amount of work examining sexuality and queer life in Africa. Gay rights has had a mixed record there. In the late 1990s, South Africa adopted the first national constitution to explicitly prohibit discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation; nevertheless, in SA, as in other parts of the continent, homophobia remains, as we can gather from the work of Steven Cohen.

“Foregrounding his own identity as a gay, Jewish man, Cohen’s provocative and daring performances question dominant, accepted narratives,” explains our new book. “His works can be seen as public interventions, in which he uses his own body to disrupt and dramatize social patterns, revealing uncomfortable truths about society at large in the process.

“In an early work entitled Ugly Girl at the Rugby (1998), Cohen, dressed in a corset, leopard-print tights and his signature elaborate makeup and entered a rugby stadium in Pretoria, where he was subjected to groping and verbal abuse by the match attendees, bringing to the fore the everyday violence of homophobia.

“In Chandelier, wearing an ornate chandelier tutu and walking on vertiginous heels, Cohen interacted with the residents of an informal settlement on the outskirts of Johannesburg that was facing imminent demolition. Juxtaposed with the squalor of the environment, his opulent, fantastical display brings emphasis to the harsh realities of the situation, shedding light – literally, with the chandelier illuminating as the performance stretches into the night – on the emotional distress of the people being forcibly removed from their home.”

Fellow SA artist, photographer, Sabelo Mlangeni (top image), doesn’t put himself in the picture, but he does cover similar ground. “Whether documenting migrant life in Johannesburg’s hostels, the night vigils of the Zionists, or the solidarity and warmth of LGBTQIA+ communities, a common thread throughout Mlangeni’s work is his focus on the collective: those aspects of life – whether cultural, religious, economic, sexual or circumstantial – around which people gather and grow,” explains our book.

“The series ‘Black Men in Dress’ was shot over a short period of time during Johannesburg and Soweto Pride, an annual one-day event for people who identify with the LGBTQIA+ community to gather and openly celebrate. Shot in black and white, the photographs in this series centralize and foreground the individual against the backdrop of the event. The title of this photograph draws attention to the subject’s headwrap, an item of clothing typically worn by women to funerals or to church, which has since become a fashion statement.”

To better understand how these two artists fit into African art, and to see many more brilliant works from this continent, order a copy of African Artists, here.