When Raphael painted St George

On St George’s Day we look at the figurative abandonment that enabled Raphael to paint such fantastic scenes

We all know dragons are only slain in fairy tales, yet the power of such a story has real-world applications, as the English who choose to mark St George’s Day today – and even those who do not – are well aware.

When an Italian nobleman sought to recognise the honour bestowed on him by a distant court, he reached for this legend, commissioning one of the greatest artists of his age to make the most accomplished, prestigious tribute money could buy.

The tale of St George, a third-century Christian soldier who saved the daughter of a pagan king by slaying a dragon, first found popularity in medieval Europe. The fifteenth-century Italian artist Raphael may have come across the story in the popular Italian collection of hagiographies, The Golden Legend.

However, Raphael painted two versions of the St George myth, not for his own satisfaction, but for Guidobaldo da Montefeltro, the Duke of Urbino, a prestigious and refined nobleman. The earlier, less-accomplished version of this scene, dating from 1504, is in the Louvre's collection, while the later, better painting is in the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC.

Montefeltro may have derived particular enjoyment from the pictures. The duke led a professional army, and, in the early sixteenth century, after years of conflict and disorder, Urbino was enjoying a period of stability and splendour; the sight of a triumphant knight would have been welcome.

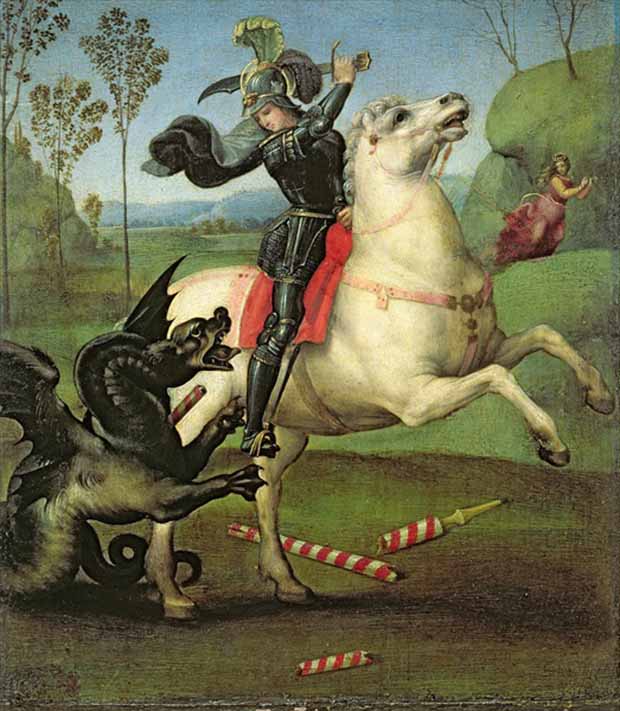

Moreover, Montefeltro had been awarded the Order of the Garter by England’s King Henry VII to strengthen the two courts' allegiance; and so the choice of St George is apt. The garter, the oldest and most senior order of chivalry in England was in part dedicated to St George, who is also the Patron Saint of England. Raphael's 1506 painting (at the top of this story) notes the link directly. In the picture, St George wears a garter upon which bears the word HONI, the first in the order’s motto ‘Honi soit qui mal y pense (Shame be to him who thinks evil of it).

However, Montefeltro didn't commission the work to burnish his own reputation, but as a tribute to the foreign court that had honoured him. Latter-day scholars believe the painting was a gift for the English king’s emissary, Gilbert Talbot, who was also a Knight of the Garter. Italy’s artistry was far better than England’s at this time, as both courts would have known, and so Montefeltro's gift projected the refinement and elegance of Urbino across Europe.

Raphael’s particular skill lay in depicting figures in a life-like manner, without having to rely on life models. As Gombrich explains in The Story of Art, “just as Michelangelo was found to have reached the highest peak in the mastery of the human body, Raphael was seen to have accomplished what the older generation had striven so hard to achieve: the perfect harmonious composition of freely moving figures.”

This harmony was the product of Raphael’s imagination, not his careful observance. When asked once asked by a courtier where he had found a model of such beauty for his 1512-14 painting, The Nymph Galeta, Raphael replied that he did not copy any specific model but rather followed ‘a certain idea’ he had formed in his mind. In so doing, Gombrich explains, the artist “abandoned the faithful portrayal of nature which had been the ambition of so many Quattrocento artists.”

No one would have been so foolish as to ask where he had found so fiercesome a dragon, yet it was this figurative abandonment that allowed Raphael to paint such fantastic scenes in such a lifelike manner, and allowed his patrons to put such skill to practical use.

For more on this great Italian artist buy a copy of our classic monograph, which features these works and much more. For greater insight into this period from one of the greatest art historians, consider our three-volume set of EH Gombrich's essays on the Renaissance.