'My job was to go treasure hunting!' Author Ian Volner on his revealing Philip Johnson visual biography

On Johnson’s birthday, the author of Philip Johnson: A Visual Biography discusses his new publication with Hilary Lewis, Chief Curator and Creative Director of The Glass House

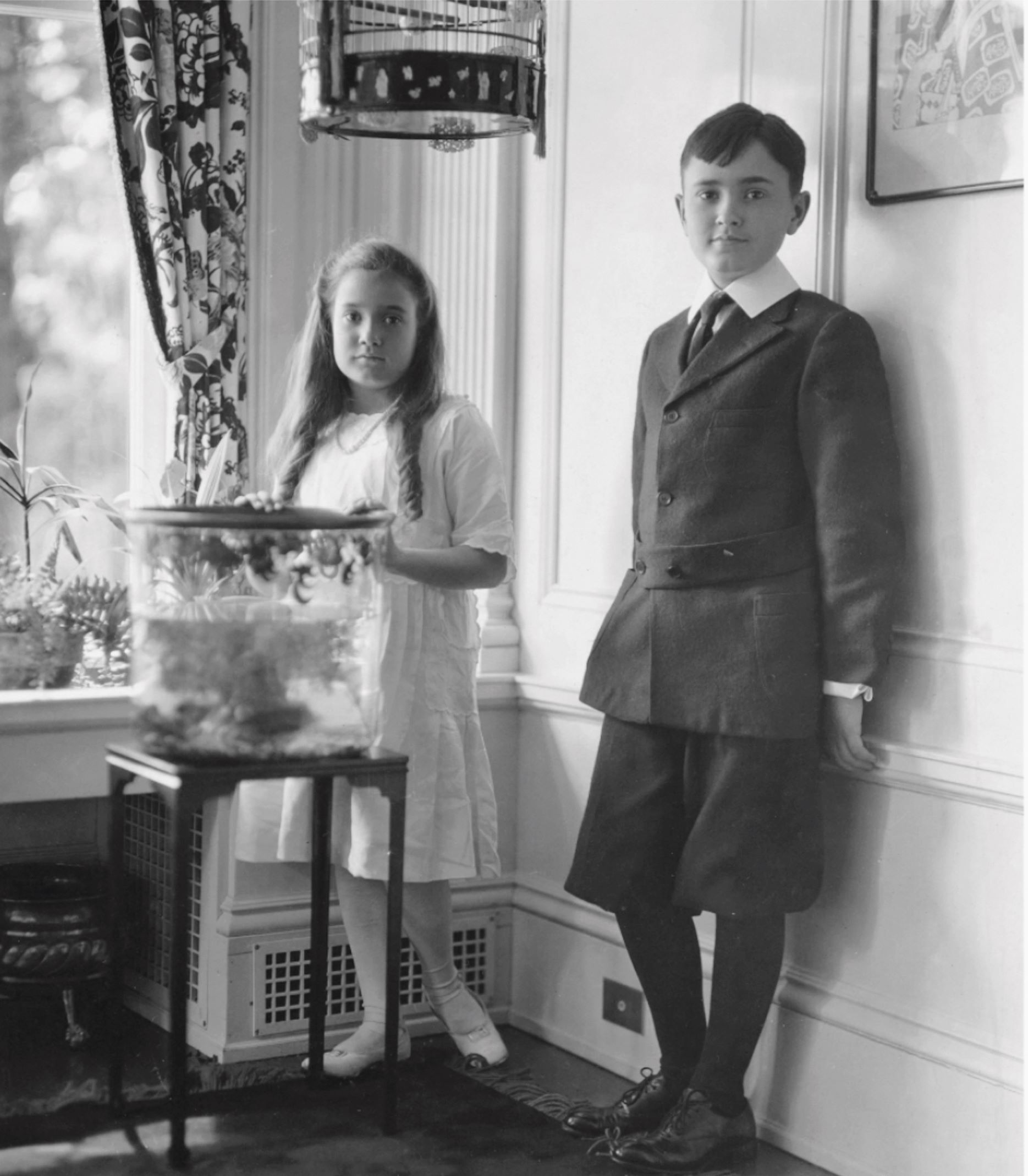

Philip Johnson might have been known for building the Glass House, perhaps America’s best-known modernist home, but he never suffered from the restrictions of a glass ceiling. Born into a wealthy family, Johnson ascended to the very peak of American society, associating with everyone from Jackie O to Andy Warhol, while building - and contributing to - some of the most important buildings of the 20th century.

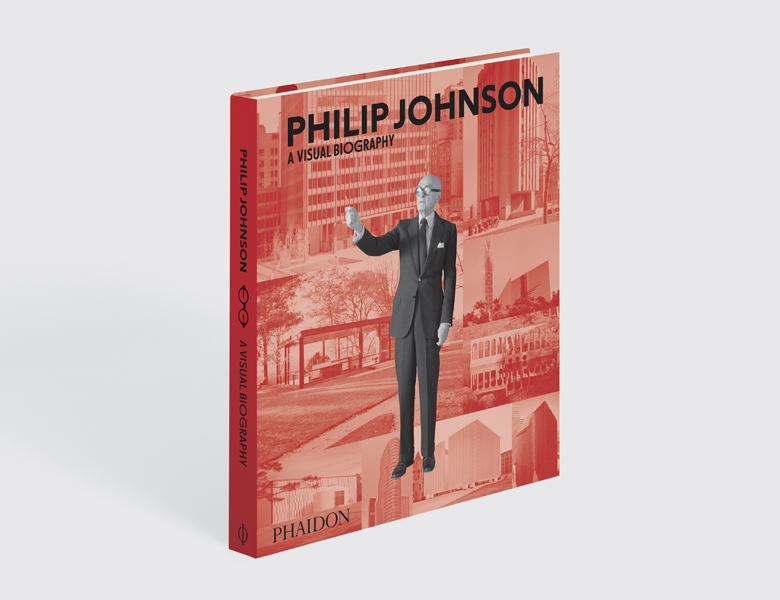

Johnson was born today, 8 July, back in 1906. To mark the 114th anniversary of his birth, we brought Ian Volner, author of our new book, Philip Johnson: A Visual Biography, together with Hilary Lewis, Chief Curator and Creative Director of The Glass House, Johnson's erstwhile home, and perhaps his best-known creation. Read on to discover how Volner tackled Johnson's career, struggled with the architect's politics, and learned to love a great deal of his buildings.

Let's start at the beginning. Why Philip Johnson? How did this project begin? Good question! The book is of a piece with other major Phaidon historical monographs published in recent years—their gigantic Le Corbusier Le Grand in particular—and Emilia Terragni, Phaidon’s estimable publisher, had been contemplating making Johnson their next subject. She approached me about the idea, and it just seemed natural to me: Johnson occupies such an outsized place in the architectural imagination, why shouldn’t he have an over-sized photographic book to match? Mind you she didn’t think much of my title idea. I figured since the last one was Le Corbusier Le Grand, we should call this one The Big Johnson. Total non-starter.

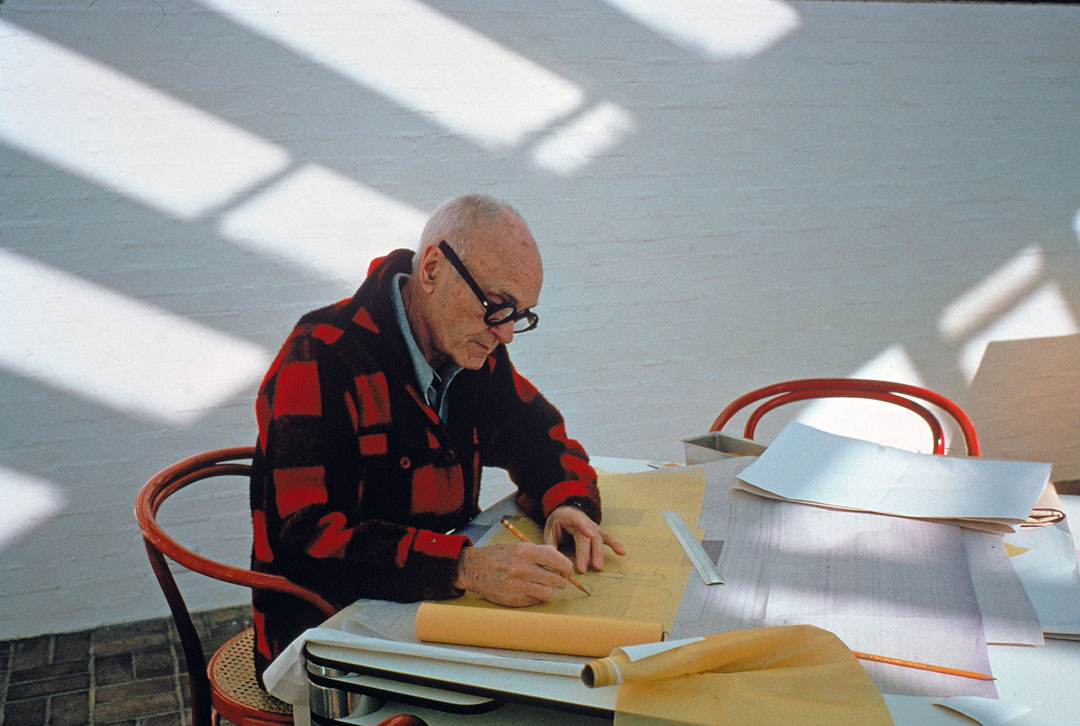

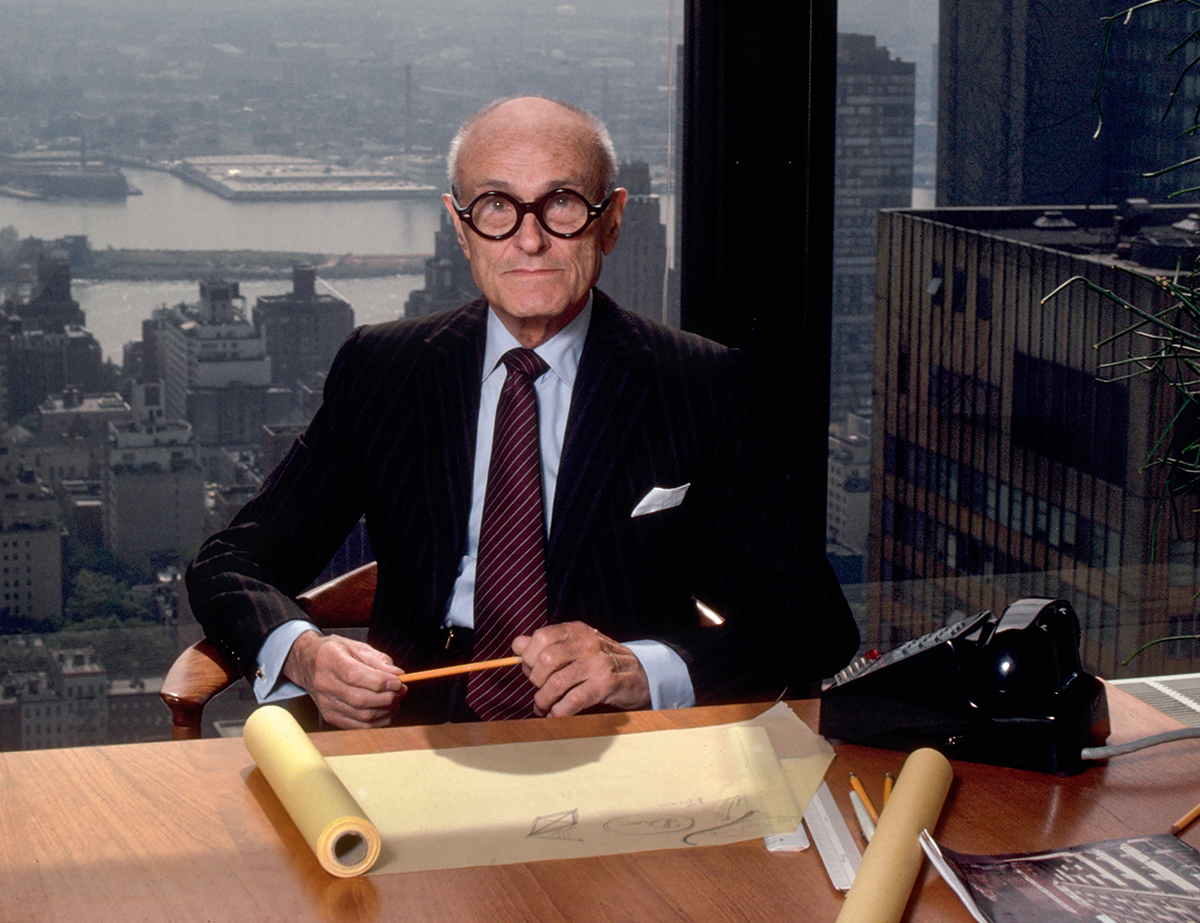

I assume you were familiar with much of Johnson's history prior to the start of the project. But what surprised you most during your research? Yes, indeed I think he’d come up in a casual conversation with Emilia long before we started the project — I’d written the essay for Annabel Selldorf’s monograph previously, and I think Emilia gathered something of my interest in Johnson while we were working on that. I’d always been pretty fascinated by him as a cultural phenom: besides Schulze’s biography, I’d been picking up every first- and second-hand anecdote I could, from as far back as undergrad, and then of course while I was writing my biography of Michael Graves I got still more info, since their stories dovetail at several points. In spite of all that background, I was frequently surprised by what I learned in the research phase — most especially by the sheer volume of material available. Naturally, in the age of the Internet, we don’t save every scrap of our own press, every cast-off drawing, every declined invitation; that was more common a generation or two ago. Still, even by the standards of other architectural archives I’ve dug around in (Frank Lloyd Wright’s, curator Arthur Drexler’s, critic Reyner Banham’s) there was simply such an astonishing quantity of surviving Johnson papers, scattered between Columbia and MoMA and the Getty Center. And that’s telling: this was somebody who wanted to keep a record. He had delegated people to save these things, allotted space in which to save them, had a whole system in place. And that for me was the most surprising discovery—seeing just how much this man had his eye on his own posterity.

This is indeed a significant visual compilation, filled with photos, drawings, articles and all types of archival material. How long did it take you to complete the project and collect the many materials? A very, very long time! I wrote and published an entire other book while this one was still getting researched and written. Altogether it was about a two-and-a-half-year project.

In some ways this feels like an exhibition, due to your focus on visual materials over text. Is it your intention to allow the reader/viewer to come to their own conclusions rather than have you direct their thinking on Johnson via narrative? Precisely. This is not, shall we say, an un-covered subject. Mark Lamster’s excellent biography came out in the middle of this book’s getting done. The only thing we could do that wouldn’t be totally redundant was to present all the material in the raw like this. My role was just to play safari guide.

You refer to Johnson throughout the text and captions as 'Philip.' Typically, writers don't refer to Frank Lloyd Wright as 'Frank' nor Ludwig Mies van der Rohe as 'Ludwig.' Why did you decide to go in this more personal manner with the text? Did you know Johnson? Nope! As I say in the book, that was how he was always discussed in architecture circles, even by those only barely acquainted with him. What’s more Schulze uses the architect’s Christian name, so there was that precedent. Most importantly, the whole tone of the book is intended to be up-close-and-personal, so it fit.

Given the length of Johnson's career, which was nearly all devoted to architecture and art, how do you make sense of his political activities of the 1930s? You cover this period with a wealth of material. As an extension of his aesthetic impulses, it made complete sense. In his architectural career, Philip was always attracted to spectacle and sensation, never mind the mechanics or the morality that lay beneath. But if you mean why did he shift to, of all things, politics, I think that at that point in his life he was not yet truly committed to architecture. He had tried out philosophy and music. Politics was another hat for him to wear. Only too late did he realise just how unbecoming it really was.

Johnson spent nearly 45 years in a relationship with David Whitney. A number of books have essentially glossed over this important aspect of his life. What was your approach to Johnson’s long life as well as his identity as a gay man? Delicate. Schulze’s book has been criticized for prurience on that score, although that may have something to do with it coming out so many years ago, before homosexuality and gay relationships became more normalized. On balance, I thought it no more or less important to treat his private life how it would be treated for any other public figure—with the special exception that being gay did indeed mean something very different than being straight in the twentieth century.

Johnson studied philosophy as an undergraduate at Harvard in the 1920s. Can you contextualize his connection to philosophy in architecture? He may have quit Hitler, but I’m pretty convinced he never quit Nietzsche. He could connect with individual philosophies as they applied to architecture — how Hegel’s thoughts could influence space-making, how Derrida could be translated into warped and complex structures—but more important than any of these was the overall ethical (or non-ethical, or trans-ethical) matrix presented by Nietzsche. Being free to reinvent oneself over and over again, not being bound by social norms, etc. etc.: for all that he leaned on Beyond Good and Evil and Also Sprach and so on, and he never stopped doing so.

__You have a section devoted to Johnson as a collector, which you placed towards the end of the book. Since Johnson was a collector before he was an architect, why place this after discussions of his architecture? __ The chapter ordering is by no means strictly chronological — we mixed it up as much as possible! So partly it was just to break up the simple biographical March of Time, which can be very boring. But also his collecting and his architecture were connected, were easier to make after we’d already introduced the Glass House compound in the earlier chapters. It’s the making of the Bunker and the Sculpture Gallery that see him really come into his own as a collector, someone who now owns enough work he has to build bigger spaces for it. And as he does so you see, through these new buildings, how his architecture is changing in tandem with his artistic tastes.

One of the most essential qualities of Johnson's home, the Glass House, is its landscape. He used to comment, 'The basic building block is trees.' While you do not have a specific section devoted to landscape, can you comment on how you see its role within Johnson's work? You’re so right! We could have had a landscape chapter as well. But then to some degree his landscape work is subsumed within those other category headings we have, Modernist and Post-Modernist and so on. I guess I’d say that his approach to landscape is symptomatic of everything he did — in that it evolved, moving from the quiet austerity of the MoMA courtyard to the frenetic monumentality of the Fort Worth Water Gardens, hitting every note in between — and also in that it always sought to surprise, to present the shock of the new, every time out.

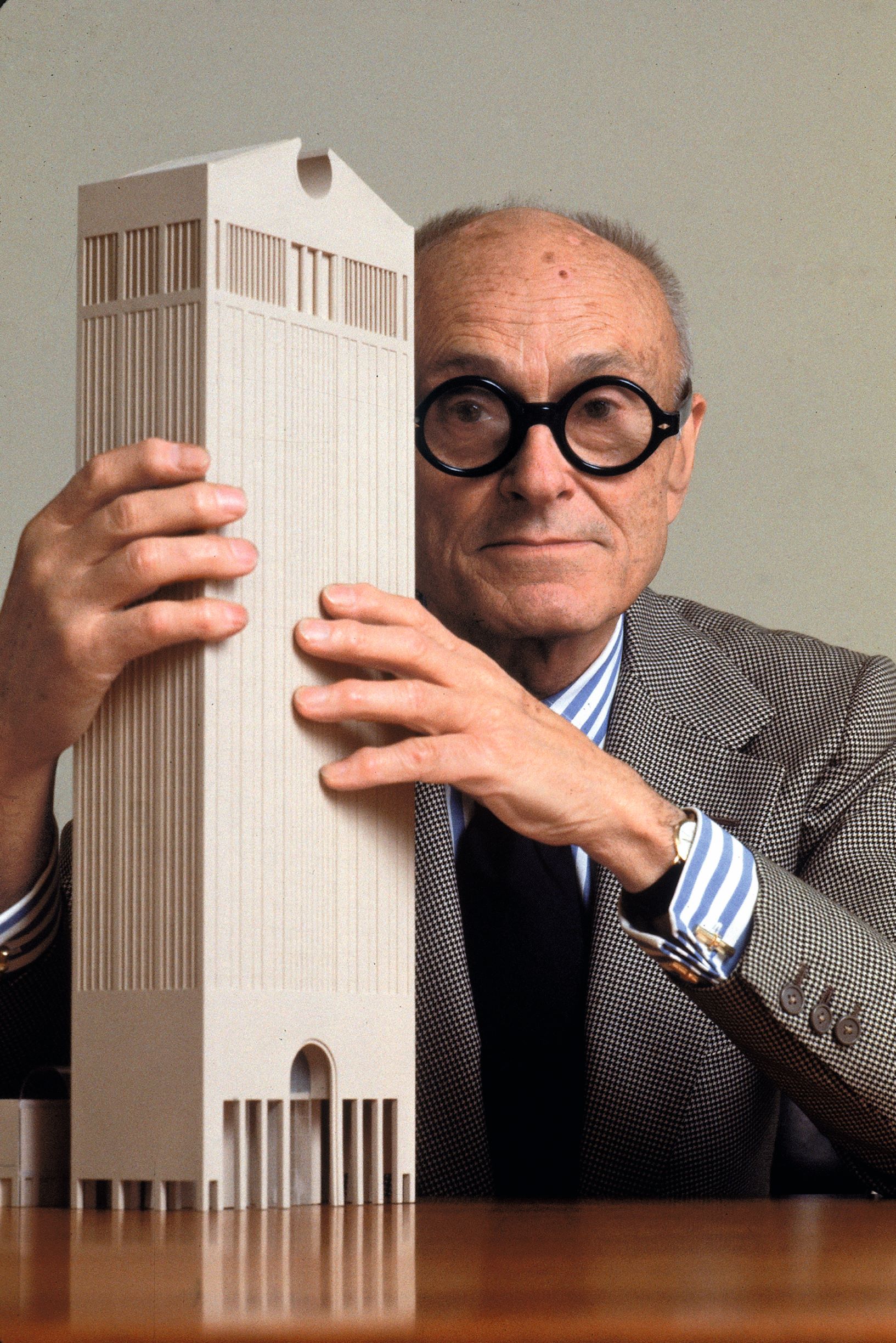

When the facade of the former AT&T building (550 Madison Avenue) in New York was perceived as being at risk, a surprising number of young people protested in an effort to see the building landmarked. Can you comment on how younger generations now (and will) perceive the work of Johnson as well as works of postmodernism? That was bound to happen, wasn’t it? People were always going to come around even to some of his most controversial work, and I think one of his most intriguing qualities is that he anticipated that, he really knew how the process of monumentalization works over time and then designed his buildings so they’d eventually be seen as exemplars of their historical moment. I expect we’ll see more of that in the years to come, that younger people will continue to defend the work on that basis.

How did your opinion of Johnson and his varied oeuvre change over the time that you worked on the book? I think it’s customary to hate your subject by the time you’re done with an exhaustive study of him or her. I suppose if I’d had to it as Lamster did, I might have felt more zapped — but my job was just to go treasure hunting! Then all I had to do was lay out all the booty and say what it was, which is a lot more fun than doing a full-dress biography. Plus, I had so much time to do it. So, I still find PJ very fascinating and feel, as I did at the outset, that his sheer ubiquity on the American scene makes him a most convenient prism for understanding what happened in architecture during his lifetime. As for his oeuvre, it’s much the same thing: some of the buildings still seem good to me, some not, though I have come to appreciate a couple that I didn’t care for before. Pennzoil Place now strikes me as one of his best. And the New York State Pavilion, which I used to think was dopey; I’ve really started to hope it can be made more accessible. Changing your mind—isn’t that what it’s all about?

Care for a little taste of the kinds of treasures Volner unearthed? Well, read on to find out about a few of the hand-drawn birthday greetings from some of Johnson's best-known friends and admirers that appear in the book.

"For all his mingling among the beau monde, it was in his own small professional niche that Philip’s friendships were the most important,” writes Volner. “Nowhere is this more evident than in the birthday scrapbooks—visual Festschrifts [celebratory books] replete with sketches and poems—prepared for him by younger architects and thinkers who, in his old age in particular, regarded him as a mentor and guiding light of the profession. Several such books were assembled over the years and were duly presented to Philip over dinner at the Four Seasons, always the scene of his greatest social triumphs."

Johnson lived an incredibly long life, dying back in 2005 at the age of 98, and, having helped pioneer modernism, became a key figure in postmodernism towards the latter stages of his career. Appropriately, our book reproduces a wealth of those hand-drawn birthday well wishes, from key figures, including the designer Massimo Vignelli, and fellow architects César Pelli, Frank Gehry, and Michael Graves, among others.

They are beautiful, creative tributes to the man - some appropriately playful too. On the occasion of Johnson’s 85th bithday, Graves sketched Johnson’s Glass House from the west with the later addition, the Brick House in the background. The inscription reads: “The best peice [sic] of Glass in America!”

Alas, there will be no such well wishes this year, but to see these images in greater detail and much more besides order a copy of Philip Johnson: A Visual Biography here.