The quest for silence and stereo in in the turntable revolution

Quieter mechanisms and double-cut grooves enabled record players to reach new sonic heights during the 1960s, as Revolution reveals

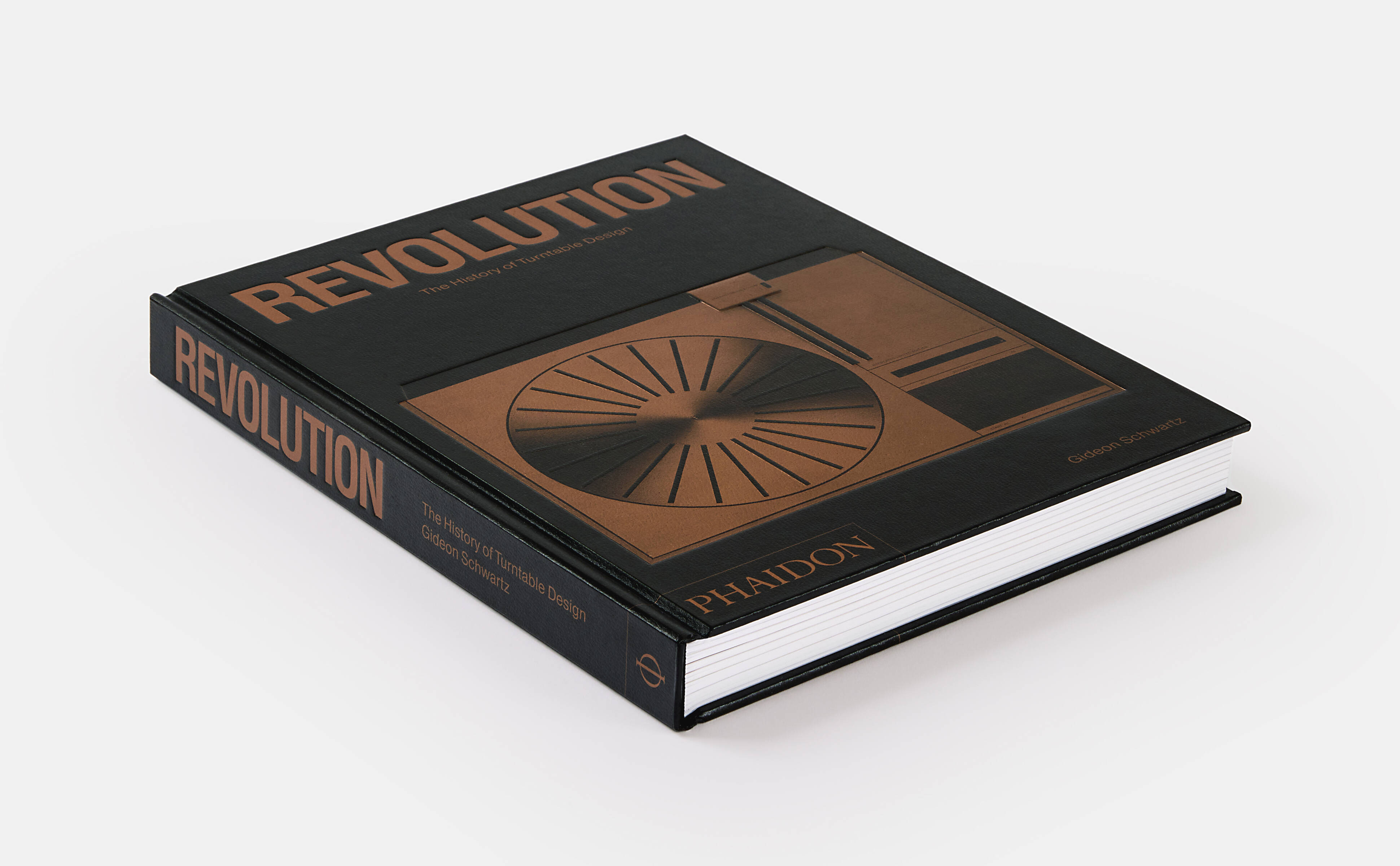

Most of us are fortunate enough to have two ears. Most record turntables only have one needle. For years that mismatch presented problems, as Gideon Schwartz explains in his new book Revolution: The History of Turntable Design.

In the opening sections of his chapter on 1960s record players, Schwartz quotes Hans Fantel, a long-standing home electronics columnist for the New York Times, who once wrote, “stereo was invented millions of years ago when two-eyed, two-eared creatures first appeared on earth. You perceive the world in pairs with your two eyes and two ears. That’s what makes your sense of sight and sound three-dimensional.”

Packing two signals into a single vinyl groove was actually achieved back in 1931 by the British engineer Alan Blumlein. “His research led him to develop a needle that could retrieve two signals from a specially cut groove, effectively resulting in stereo reproduction,” writes Schwartz. “Creatively combining the antiquated hill-and-dale method espoused by Thomas Edison and the lateral technique championed by Emile Berliner, he successfully put two separate channels within the same groove.”

Yet record companies were cautious about introducing stereo records, and only shifted their positions after tape companies such as Ampex had offered consumers stereo tape machines, while firms such as Westrex had developed a stereo tape-to-vinyl recording process that was affordable, effective, and produced stereo records that could still be played on mono turntables.

On August 26, 1957, Westrex invited the industry’s leading engineering representatives to a demonstration in its Hollywood laboratory,” writes Schwartz. “While it was neither the role nor purpose of the attendees to determine the stereo-cutting standard for the industry, the collective enthusiasm for the Westrex demonstration led to the adoption of the Westrex 45/45 system by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) on December 27, 1957.”

Other developments were also driving turntables forward. Manufacturers were finding ways to make the turntable platters rotate accurately and powerfully without affecting sound quality. This was no easy task, though audio engineers came up with a number of solutions.

There was the idler drive, “in which a motor-driven rubber wheel sits underneath the platter,” writes Schwartz. “This design isolates the idler wheel to prevent the vibrations created by the motor from resonating through the platter.”

In 1965 German manufacturer Dual incorporated this system into its 1019 model, solidifying its presence in the market, which remains popular to this day.

“Aficionados of 78-rpm discs are drawn to the 1019 for its high torque, and many examples are sought out for meticulous restoration,” writes Schwartz.

In a further attempt to reduce unwanted noise, the 1960s also saw the introduction of belt-drive turntables. “Implementing a smaller and less powerful motor, which spun a rubber belt that was wrapped around the platter, the belt-drive mechanism had an isolated motor and was believed to absorb vibrations.”

TD124 Statement Turntable, Thorens, restored and upgraded by Artisan Fidelity, 2017. Picture credit: Artisan Fidelity

The high-end Swiss manufacturer Thorens incorporated a hybrid of belt and idler drive in its now highly sought after TD 124 MKII, which the company released in the mid 1960s. “Compared favourably to the Garrard 301 and 401, the Thorens TD 124 MKII would join the top tier of classic turntable designs,” writes Schwartz. “Even Bang & Olufsen borrowed the 124 for its own branded Beogram 3000 model. Today, existing models of the TD 124 MKII are painstakingly restored by firms such as Swissonor and Schopper in Switzerland and Woodsong Audio in the United States.”

And, there was one, final torque mechanism which came into play towards the end of the 1960s which sent vinyl off on an entirely different course: direct drive.

Gideon Schwartz

“The brainchild of Shuichi Obata, an engineer for Technics, a brand of Matsushita (which became Panasonic), this mechanism implements a motor located under the platter, directly coupled to and spinning the bearing upon which the platter is placed,” writes Schwartz. “Avoiding problems of wear and tear on the belt and slow start-up times, direct-drive tables were initially aimed at the professional sector, with Obata’s 1969 introduction of the legendary SP-10.

Revolution

“Expanding into the consumer market with the later SL-1100 and SL-1200 models, Technics turntables would eventually find permanent residence in DJ circles beginning in the 1970s and continuing through the 2000s,” the author concludes. For more on this and to see many more beautiful turntables, order a copy of Revolution here.