The Art of the Plant – Leonardo da Vinci

Artist or scientist? Discover why da Vinci's botanical drawings lie at the very heart of this Renaissance Man's work

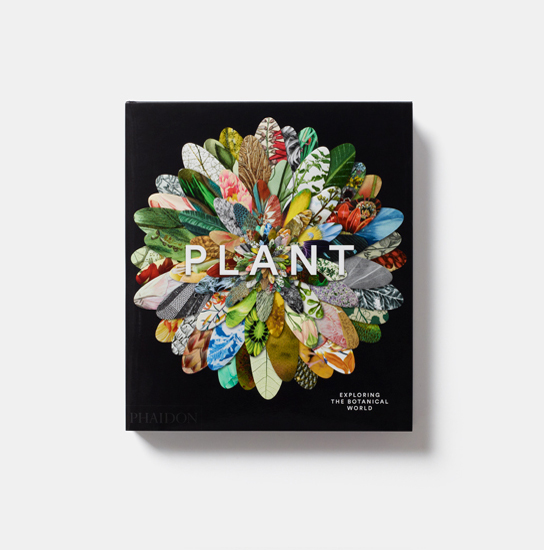

Our new book, Plant: Exploring the Botanical World, features a wide variety of botanical representations though the ages, with 300 of the most beautiful and pioneering images ever. Botanists and other scientists have produced many of these images. However, fine artists created many others.

How should we class this inclusion from the great Renaissance master Leonardo Da Vinci? Its categorisation is problematic in this regard, not only because Leonardo’s working life had as much in common with that of a contemporary research scientist as it had with a contemporary artist. This drawing of a trio of plants is hard to class as either an artistic undertaking or a scientific diagram, because it seems to record and investigate both scientific and artistic matters, as our book explains.

“If there is one overriding characteristic of Leonardo’s drawings, it is his quest to go beyond mere description. A supreme draughtsman, he captured the smallest details with great accuracy by spending hours in focused observation as he sought to reach a deeper understanding of his subject. Driven by an insatiable curiosity about the world around him, the original Renaissance man used drawing not only to sketch details for his larger paintings but also almost as an analysis of life forces: the flow patterns of turbulence in water, the tension within the muscles of the human body and, in this drawing of Star of Bethlehem, the dynamic energy of the swirl of leaves from which the flowers burst forth.

"On the same sheet, a drawing of a wood anemone reveals the more delicate fragility of the flowers on their stems, while the close-up observations of the cupped seed heads of the sun spurge (bottom left) show his forensic fascination with the anatomical arrangement of parts. It was through such deep observation that Leonardo was able to integrate the living world so convincingly into his paintings. These particular drawings may have been used to create the foreground of his painting of Leda and the Swan, which was lost in the seventeenth century but is known in copy.”

For more lively insight into natural order, buyr a copy of Plant: Exploring the Botantical World here.