The mechanised world of Francis Picabia

On the anniversary of his birth we take a look at what made the reluctant Dada pioneer tick

The anniversary of Francis Picabia's birth today made us turn to our forthcoming Dada book for some detailed and very illuminating insight into his influences and inspirations.

Along with Marcel Duchamp, Piacabia came to New York in 1915 ostensibly to avoid the war in Europe. The pair were already well known in the New York art community due to their having participated in the Armoury Show in 1913, where Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase had created uproar. The two artists were catalysts for young Americans to break with European traditions and experiment in non-conventional subject matters and materials. Inspired by American machinery, Picabia developed his playful, erotic mechanomorphic drawings while working with the photographers and artists of Alfred Stieglitz’s Gallery 291. Stieglitz, a pioneer in the art of photography was also a promoter of the European avant grade in New York.

Picabia and Duchamp in turn were stimulated by American artists and writers. When Picabia arrived in New York in 1913 he immeditately made a series of watercolours which expressed “the spirit of New York as I feel it, and the crowded streets of your city as I feel them, their unrest, their commercialism, their atmospheric charm.”

Yet it was his second visit to America in 1915 which brought, in Picabia’s words “a complete revolution in my methods of work. Almost immediately upon coming to America it flashed on me that the genius of the modern world is in machinery, and that through machinery art ought to find a most vivid expression.” In his statement, Picabia clearly attributes his discovery of machine drawings to his experience of American culture. The works below should be viewed with that in mind.

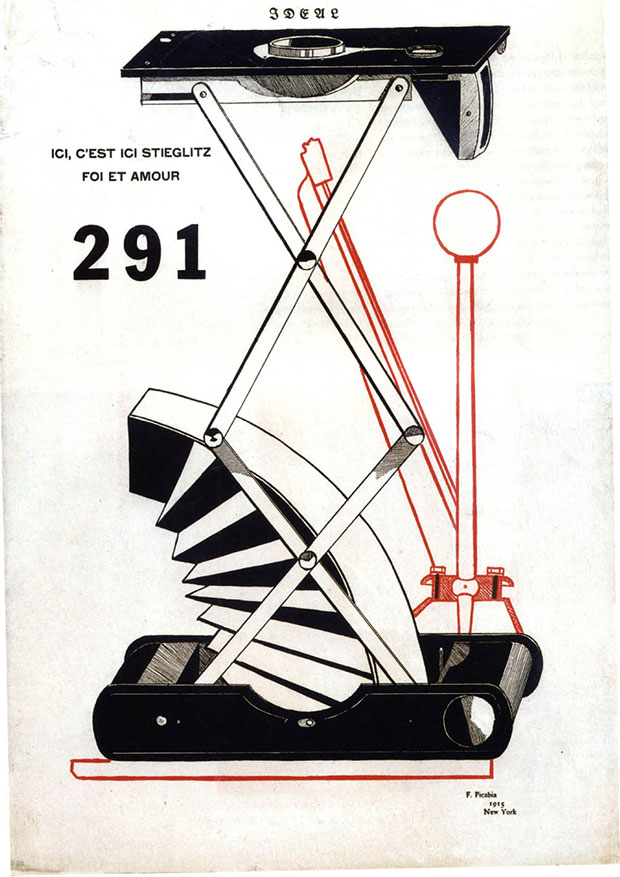

Ici, c’est ice Stieglitz 1915 Picabia met Alfred Stieglitz, photographer and gallery owner, on his first trip to New York in the spring of 1913. When Picabia returned to the United States in 1915 he quickly became a contributor to Stieglitz’s journal 291. This ‘machine portrait of Stieglitz’, appeared in a fold out set of five mechanical portraits in the July/August 1915 issue. The rest of the series comprised a self-portrait, a ‘young American girl’ (possibly Agnes Meyer). Marius de Zayas and Paul Haviland. Stieglitz is represented as a sort of camera that has merged with the gear shaft and brake of an automobile. Despite the flattering words ‘foi et amour’ (faith and love), the machine-Stieglitz is a dysfunctional contraption; the bellows of the camera are sagging, the car’s gears are in neutral and the brake is engaged!

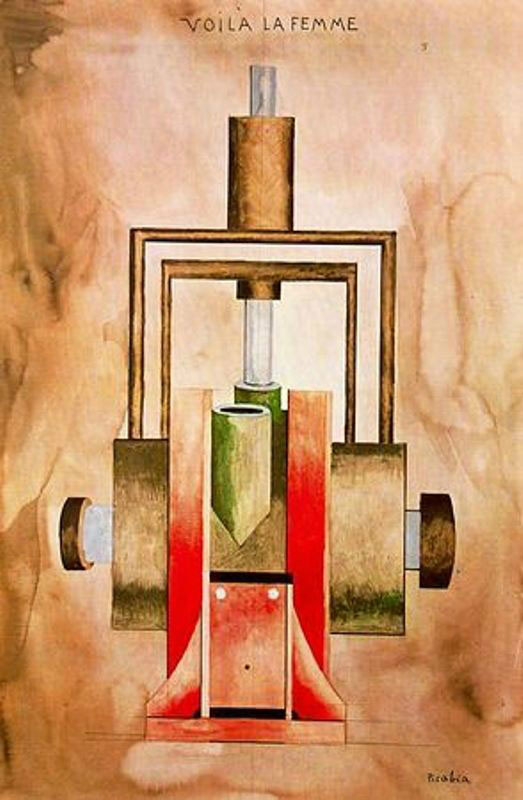

Voila la Femme 1915 Behold the Woman was one of 16 works exhibited in Picabia’s second show at the Modern Gallery, New York, which took place in January 1916. The pieces are representative of Picabia’s continuing interest in the use of machine imagery to make statements about the human condition. This work depicts a symmetrical ‘female’ machine, iconic rather than functional. The central double cylinders, and the blue piston shaft that penetrates one of them, suggest a sexual theme. This is common to many of Picabia’s machine images but went unmentioned by contemporary critics.

Fille née sans mere 1916-18 Picabia’s first version of this theme was a pen and ink drawing of a mechanomorphic being, also entitled Girl Born Without A Mother, that was reproduced in the June 1915 issue of 291. Although quite different in materials and style, the later image reprints the asymmetrical composition found in the first. Picabia appropriated a pre-existing diagram of a railway machine and remade the image by painting in a background of gold, thus covering up unwanted portions of the original image. He also added areas of green gouache to the remaining visible aspects of a flywheel and shaft. The resulting collage-like image exemplifies Picabia’s interest in the metaphors of machines and sexuality: as the flywheel turns, the shaft moves up and down replicating the mechanics of sexual intercourse. Further, the idea of a girl born without a mother is a reverse ‘virgin birth’, of an entity ‘born’ of the male, industrialized world. Want to go further with Picabia and Dada? Then you can pre order our Dada book here.