Like clear answers? Then don't look at abstract art

A new Italian study suggests that a desire for ‘cognitive closure’ might limit our appreciation of abstract works

It’s not always easy to say what a work of art is supposed to mean. Indeed, abstract art doesn’t, by definition, depict anything in particular, and may attempt to express the kinds of ideas, feelings and mental states not readily put into words. Some gallery goers find this ambiguity frustrating. Yet a new social study overseen by Antonio Chirumbolo, assistant professor at the Sapienza University of Rome, suggests that having an open mind might actually help with the appreciation of abstract art.

Professor Chirumbolo’s recent paper describes a series of experiments carried out to discover whether a preference for ‘cognitive closure’, or the desire for clear, quick answers to vexing questions, also prejudices viewers against abstract painting.

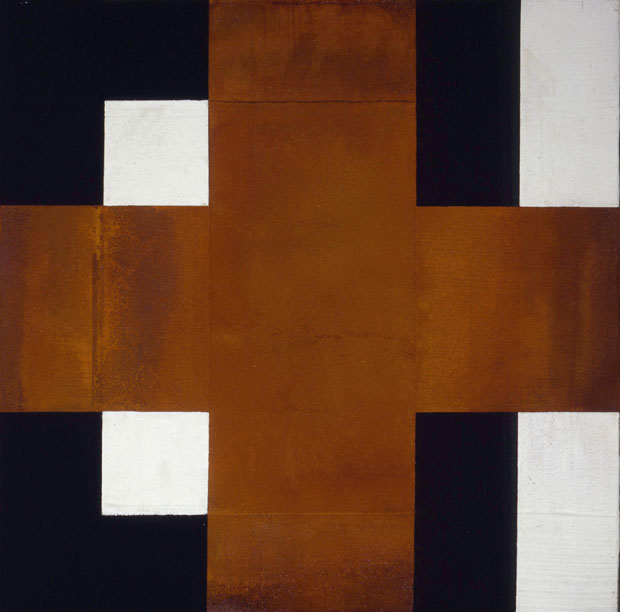

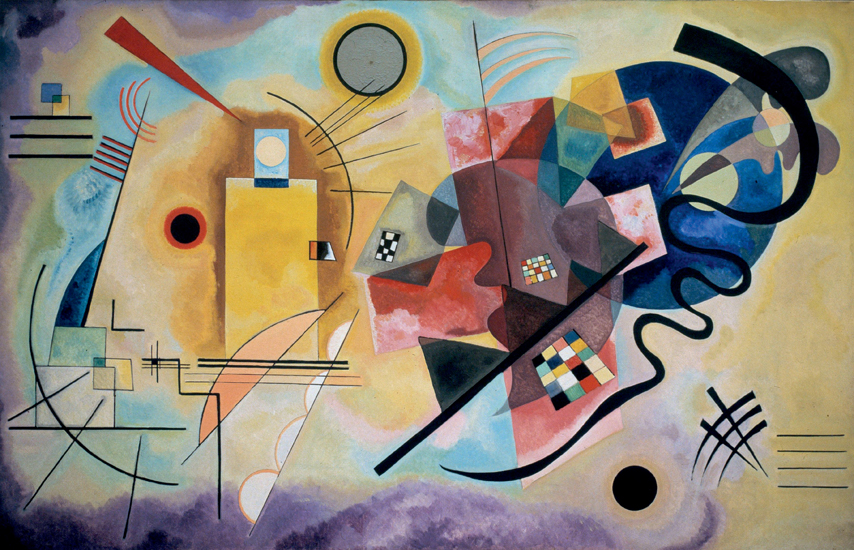

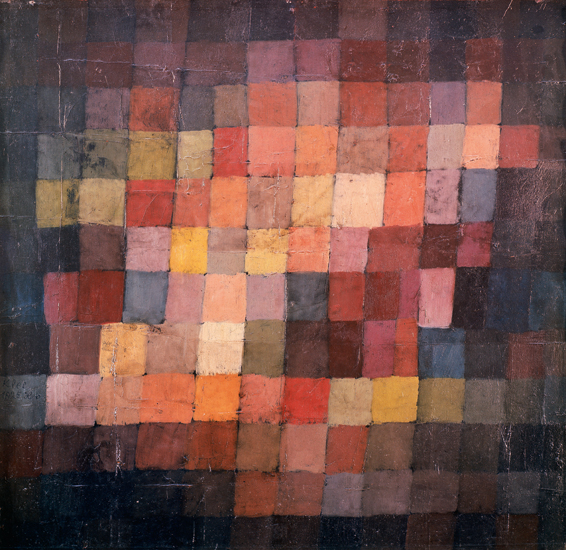

In the first study Chirumbolo and his colleges showed a group of young women with no formal training in art or architecture a series of figurative works by the likes of Canaletto and Vermeer, as well as a selection of abstract paintings by the likes of Klee, Pollock and Kandinsky. The subjects were asked to associate certain positive or negative words with the works. On the whole, the group preferred the paintings depicting the real world over the abstract works. However, those with the strongest desire for cognitive closure, who made the quickest and clearest in their associations between the pictures and the words, were also those most prejudiced against the abstract paintings. Chirumbolo expected that.

However, the academics also wanted to find out whether this desire for quick answers could be manipulated. So, the professor took another set of women, selected using similar criteria. First they carried out the same test. Then, one section of the group was asked to remember a difficult series of nine numbers, while another section were asked only to remember one number.

The subjects then carried out the test again. Chirumbolo theorised that the strain to recall a large group of numbers would, for a brief period give this select group a preference for quick, simple answers. His hypothesis was borne out, with the group asked to remember the longer chain of numbers, developing a measurable dislike for abstract art.

What can we draw from this? Well, Chirumbolo argues that, “when information processing is more costly and effortful, the desire for unambiguous and stable knowledge predominates, and anything which runs counter to this is perceived as unpleasant and displeasing.”

In short, perhaps it's best not to memorise a shopping list before going to a de Kooning exhibition. And, more usefully, try to keep an open mind when looking at art. Meanwhile, for greater insight into non-figurative painters, consider our book, Painting Abstraction.