The unexpected pleasures of art museums in four Artifacts

They’re great to admire, good for the ‘Gram, and sometimes even a fine place to meet a life partner, as our new book shows

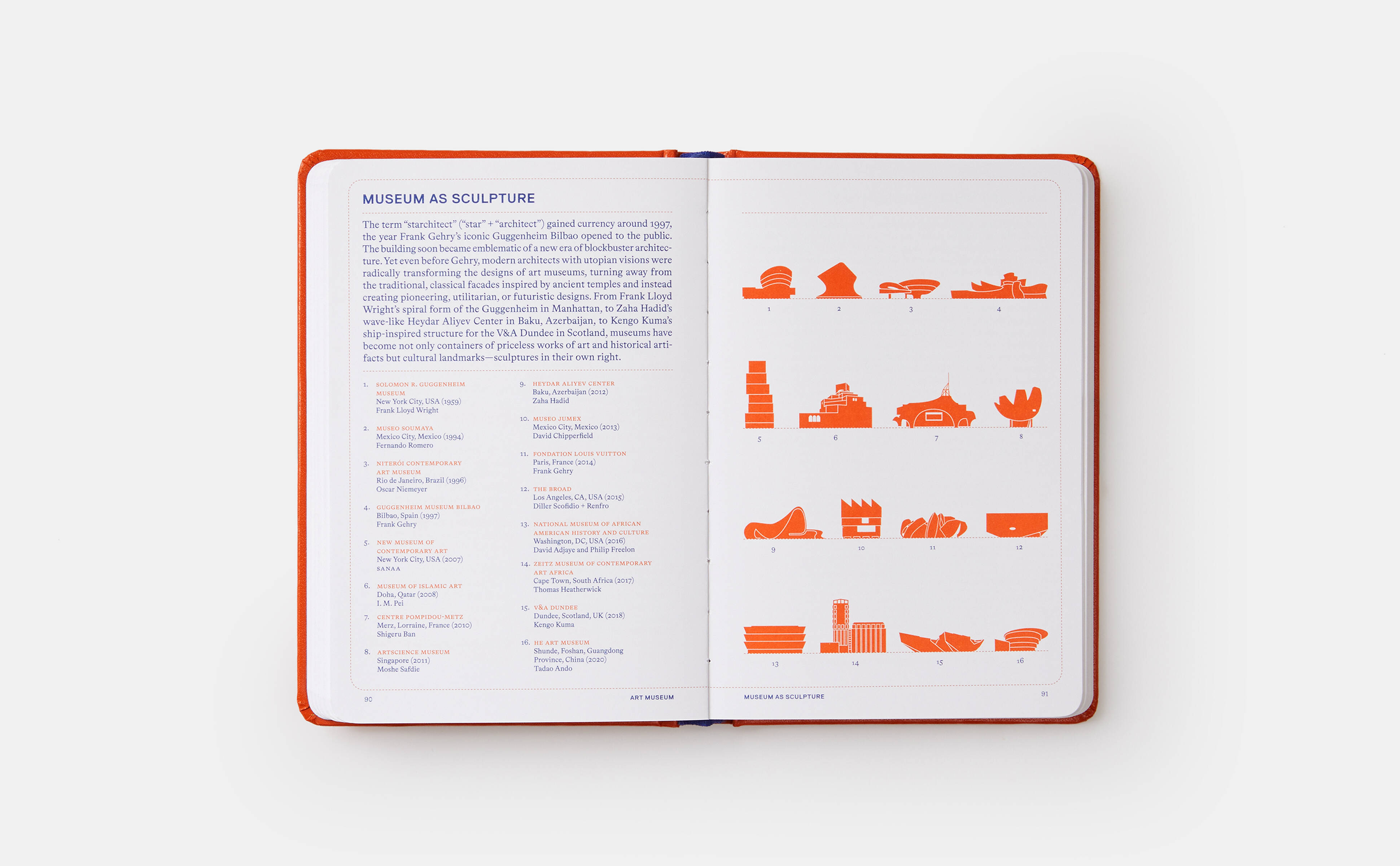

Why do we go to art museums? In our new book, Artifacts: Fascinating Facts about Art, Artists, and the Art World, Phaidon’s editors begin their Art Museum section outside these institutions, sizing up the silhouette they cast over the world’s skylines in a section entitled Museum as Sculpture.

“From Frank Lloyd Wright’s spiral form of the Guggenheim in Manhattan, to Zaha Hadid’s wave-like Heydar Aliyev Center in Baku, Azerbaijan, to Kengo Kuma’s ship-inspired structure for the V&A Dundee in Scotland, museums have become not only containers of priceless works of art and historical artifacts but cultural landmarks—sculptures in their own right,” explains the text in the book, beside a grid of appropriate illustrations.

While many of us are drawn to those seductive exteriors, there are still plenty of reasons to go inside, even if only for a moment or two. In Artifacts’ section, Looking at Art, the book’s editors alight on a series of studies measuring the average amount of time visitors actually spend regarding a work.

This ran from 27.2 seconds, according to a 2001 study at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, to 28.63 seconds, as found in a 2017 study at the Art Institute of Chicago Average. Why this sight uptick in the 21st century, during an age when many believe our attention spans are shrinking? Artifacts notes that, in this later study, “museumgoers spent much of that time taking selfies in front of the artworks,”; maybe those extra 1.61 seconds were spent deciding how good this or that painting would look on Instagram.

Anyone visiting a major art museum in the hope of finding sources of equality or social justice might be disappointed. Despite many institutions’ high-minded policies and public declarations, Artifact’s section entitled Permanent Collections, reveals that a majority of works owned by museums were made by white men, with women and non-white artists underrepresented, at least when it came to art made by a named, identifiable creator.

The book cites a 2019 study from Williams College, Massachusetts, examining the troves of 18 large museums; it indicated that, while white, male artists denominated, there was still some ambiguity surrounding older, unattributed items.

“Historically, art and artifacts from different parts of the world were collected without establishing who created them, resulting in a large number of anonymous holdings,” explains the text in Artifacts, before the book goes on to quote one of the Williams College’s authors, mathematician Chad Topaz. “The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston,” Topaz said, “boasts 85,000 works of art from Egypt, the Near East, Greece, Italy, and other areas. These generally have no identifiable artist.”

Nevertheless, if museums can’t bridge the gender gap, they can still bring the sexes together. In the section Reflections on Exhibitions (From Abstract Expressionists), Artifacts quotes everyone from Willem de Kooning to Agnes Martin. Most focus on the financial or critical results of the shows, but one contributor recalled the social dividends of a certain show.

“It was the artist John Graham, who was well-known before the war, who arranged what was for me a key exhibit,” the artist Lee Krasner is quoted as saying. “Here was this invitation out of the blue to show alongside of Picasso, Matisse, and who knows whom else. There were to be three young American painters. Myself, de Kooning, whom I well knew, and an unfamiliar name, Jackson Pollock. I thought I knew everyone painting in any sort of modem or abstract manner in New York; but who, I asked myself, was this Pollock? I had to go and see.” Krasner married Pollock a few years later, in 1945, and the pair became one of the best-known artist couples of the 20th century.

For further bite-sized insights into artists, art and the art world, order a copy of Artifacts here.