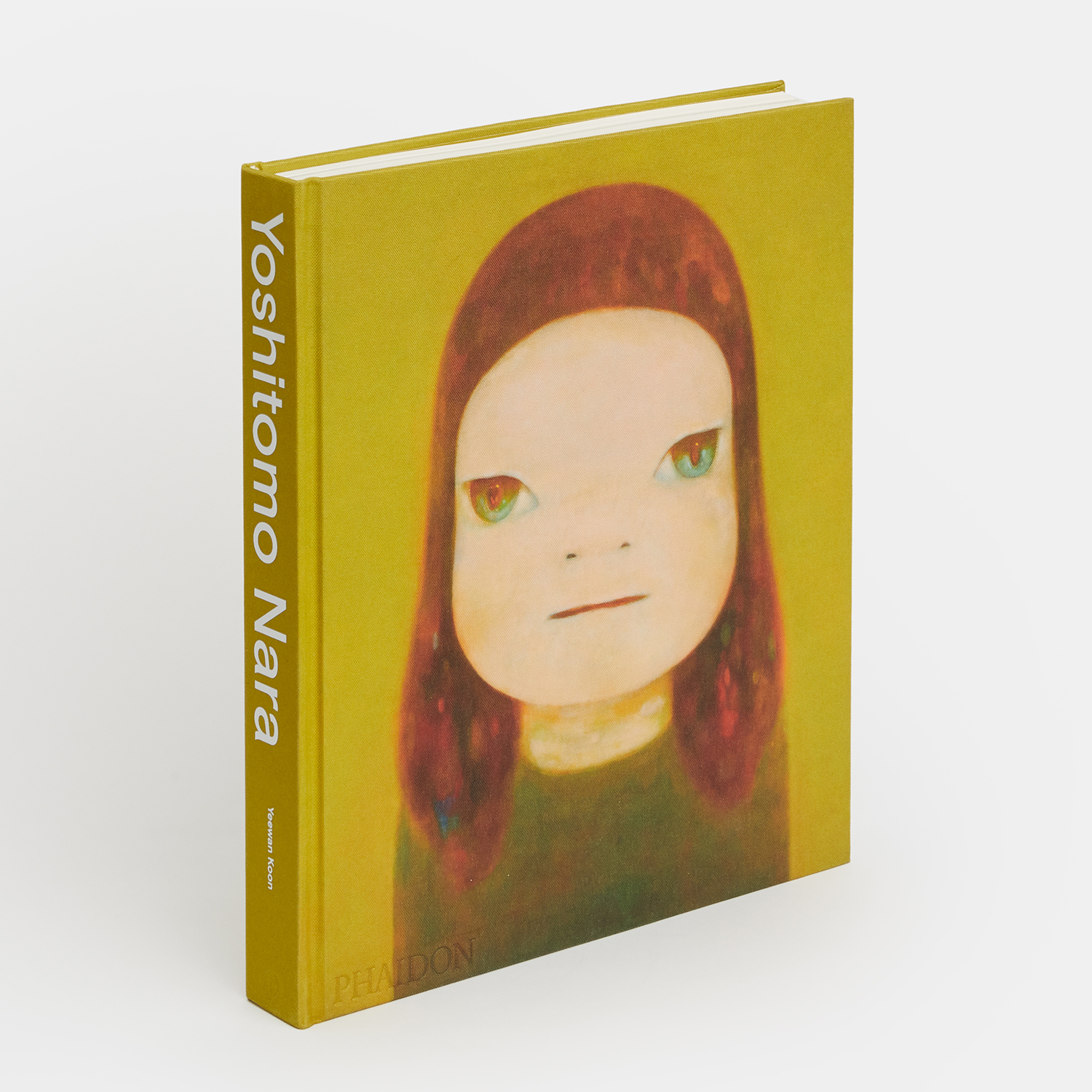

Why does Yoshitomo Nara’s girl have a knife in her hand?

Our new book on this Japanese contemporary artist tells the fascinating story behind Nara’s best-known work

In 1991, while studying at the Kunstakadamie Dusseldorf, Yoshitomo Nara painted perhaps his best-known work, The Girl with the Knife in Her Hand. It was, as our new book on this contemporary Japanese artist makes clear, “a seminal work that marked the beginning of his paintings of big-headed girls.”

Where did she come from? Well, some elements of this childlike figure lie in the artist’s own childhood. Nara was born in 1959 in the small castle town of Hirosaki in Aomori prefecture, in the far north of Japan. The town lies close to Mount Iwaki, an inactive volcano which, author Yeewan Koon explains, “is known for its sacred powers for children, and temples and shrines often incorporate the popular bodhisattva Jizō, a protector of children and the unborn."

Contemporary statues frequently depict Jizō with childlike features, and worshippers often dress them in red cloaks, bibs, or hats in a ritual that asks for protection, good karma, and the remembrance of lost children.

Nara’s grandfather was a Shinto priest, and this Japanese folk religion, coupled with a rural, though fast developing environment, left a lasting impression on the artist. However, there were newer influences too; Nara loved popular music from an early age, and would tune into the US Forces radio station. He bought his first single, by the popular Japanese band Takeshi Terauchi and the Bunnys, when he was just eight-years-old, and these poppier elements remained with him well into adulthood.

Koon pays particular attention to the Japanese concept of kawaii that arose in the late twentieth century, which is often translated as ‘cutenness’. Say the word, and many of us might picture something like Hello Kitty. Koon however, offers a number of more detailed translations:

"1. Looks miserable and raises sympathy. Pitiable. Pathetic. Piteous. 2. Attractive. Cannot be neglected. Cherished. Beloved. 3. Has a sweet nature. Lovely. (a) (of faces and figures of young women and children) adorable. Attractive. (b) (like children) innocent. Obedient. Touching. 4. (of things and shapes) attractively small. Small and beautiful. 5. Trivial. Pitiful (used with slight disdain).”

Nara’s Girl With a Knife in Her Hand certainly fits this description, as do many of the subsequent big-headed girls the artist painted over the following years. “Her childlike expressions resonate with adult emotions, her embodiment of kawaii carries a dark humour, and any explicit cultural references are intertwined with personal memories.”

“On a canvas of sumptuous purples stands a little girl in a ruby-red dress staring up at her audience: us, the adults who loom over her,” he writes. “We take in the exaggerated roundness of her face, her wide bean-shaped eyes, and the lock of hair grazing her forehead. And then we notice the knife in her hand. In that moment, any assumptions we may have had about her innocence are overturned. Outlined in thick black lines, The Girl with the Knife in Her Hand stands in a space between the flattened surface of drawing, the world of illustrations and comics, and the material textures of painting.”

The girl isn’t simply cute or simply vulnerable; she isn’t especially well-armed, but she does, certainly still pose some threat; she’s comic to some degree, but would also look a little out of place in a normal comic. These contradictions make for an effective work of art.

“Nara holds a deep-seated belief that art needs to have the affective capacity to generate empathy and affinities between people who share a delight in the complexities of its expression,” writes Koon. “The challenge he sets for himself is how to reach that potential, and doing so requires him to transcend his own ego so that his child figures can independently create connections with their viewers.”

The knife may be sufficiently sharp to carve out such a connection, but it probably couldn’t do much more damage. As Nara himself put it in a 2005 interview: "Look at them, they are so small, like toys. Do you think they could fight with those? I don’t think so. Rather, I kind of see the children among other, bigger, bad people all around them, who are holding bigger knives...."

For more on this work as well as many, many other paintings and sculptures, order a copy of our Yoshitomo Nara book here; it is the definitive monograph on the life and career of this internationally acclaimed artist.