The Lives of Artists – Vija Celmins

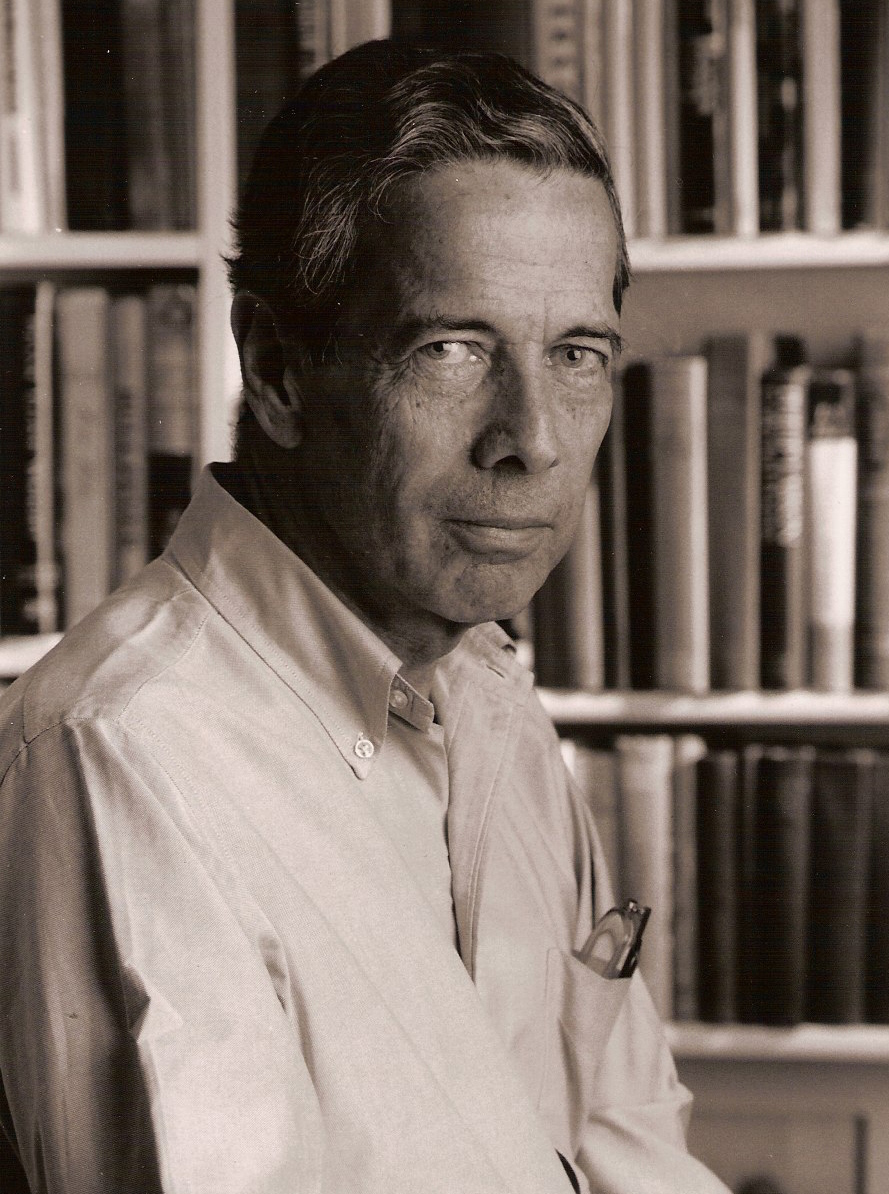

The New Yorker writer Calvin Tomkins describes the tough upbringing and robust attitude of one of America’s leading émigré artists

If you want to know what it’s like to be in the presence of important and groundbreaking artists, you should really ask Calvin Tomkins. Over the past 59 years, Tomkins has profiled almost every culturally significant figure in the contemporary art world for The New Yorker magazine.

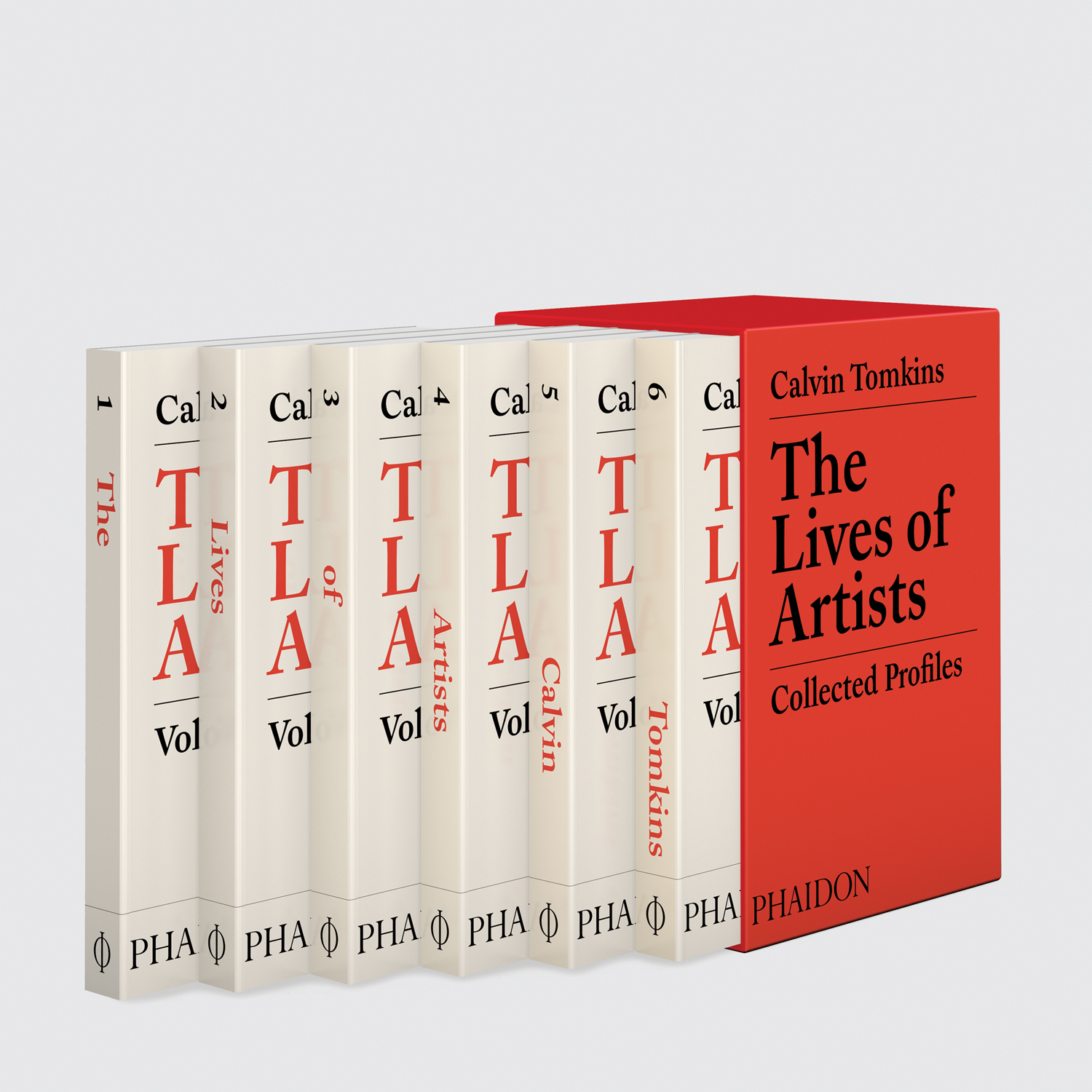

Our new six-volume anthology of his work, The Lives of Artists, brings these profiles together. There are many delightful long reads in there, but there are also moments when, in just a few finely chiselled sentences, Tomkins describes the range of impressions and emotions one might experience meeting an artist for the first time, face-to-face. Take these lines on the Latvian-born, US-based painter, Vija Celmins.

“Growing up in Indianapolis, Celmins soon learned to fend for herself. ‘My mother and father paid no attention to me whatsoever,’ she said. ‘They were too busy with their own lives. This is maybe what’s strong in me, that my parents were like peasants—they had their own way of dealing with things.’ Her father, Arturs, worked long hours as a carpenter—in Latvia, he had been a bricklayer and then a small-scale builder. Milda, her mother, took care of other people’s children and was a laundress in a hospital.

When Celmins was ten, her sister, Inta, eight years older and about to enter college, contracted tuberculosis and spent the next three years in hospitals. Their shared bedroom was now Vija’s alone, and she spent a lot of time in it, with the door closed. Drawing and reading were her refuge and her solace during her first year in America, when she was struggling to learn English.

She could read in Latvian, and by the end of the year she was reading fluently in English. (She is still an avid reader of novels and nonfiction, as well as books on art.) Eventually, she emerged from her shell, made friends at school, became a track star in running and the high jump and, as the class artist, did the illustrations for her senior yearbook. ‘I never even thought about Latvia,’ she said.”

That’s quite a formative immigrant experience. However, for a better handle on Celmins’ own, personal sense of place in the art scene of the time, consider the following passage, from later in the profile.

“The L.A. art scene was a men’s club—women artists were scarce, and not especially welcome—but ‘Vija was highly respected from Day One, by everybody,’ [artist Tony] Berlant said. ‘It’s not that she thought she was as good as the men. She thought she was better than anybody.’ Celmins had close friendships with male and female artists, but she was unconcerned about trends and expectations and fitting in. Both Celmins and Berlant remember having long, philosophical discussions with the artist Robert Irwin, who taught at U.C.L.A. ‘Vija has perfect taste,’ Irwin once told Berlant. ‘She doesn’t like anything.’”

In that wonderfully acid line you get just how uncompromising Celmins is, and how her fellow artists recognized and respected that quality. For more encounters like this order a copy of The Lives of Artists here. This six-volume set includes 82 of Tomkins's most significant profiles dating from 1962 to 2019. Part art history, part human interest, Tomkins offers insights and observations about the artists, their work, and the ever-changing art world they inhabit. Buy The Lives of Artists here.