Gombrich Explains René Magritte

The surrealist, born on this day in 1898, didn’t break with artistic techniques, he employed them on his dreams

It’s not inaccurate to think of early Modernism as a continuous attempt to overturn conventions. In a chapter of The Story of Art entitled Experimental Art: the first half of the twentieth century, the great art historian EH Gombrich surveys the various endeavours to break with the past. Cubism, Fauvism, and Expressionism were all in play during the early decades of the last century, each an attempt, as the writer puts it, "to destroy the pockets of resistance, or strongholds of academic, painterly conventions which made artists apply forms in their pictures that they had learned to produce, rather than paint what they really saw.”

However, there was one early twentieth-century movement that upended this trend. Rather than break down academic formalities to capture nature as they saw it, these artists used formal, painterly techniques to paint scenes that could never be found in nature.

A century ago, this really was a novel idea. Having surveyed the tactics used by other Modernists, Gombrich concludes: “There was one way that had only rarely been explored in the past: the creation of fantastic and dream-like images. True, there had been pictures of demons and devils such as the ones in which Hieronymus Bosch had excelled, and also grotesques such as the window by Zuccaro, but perhaps only Goya had succeeded in making his mysterious vision of a giant sitting at the edge of the world wholly convincing.

It should be remembered that the artists who pursued this path weren’t simply entering a fantasy land, but rather attempting to capture some greater truth. As Gombrich explains, “the name Surrealist was coined in 1924 to express the longing of many young artists to create something more real than reality itself.”

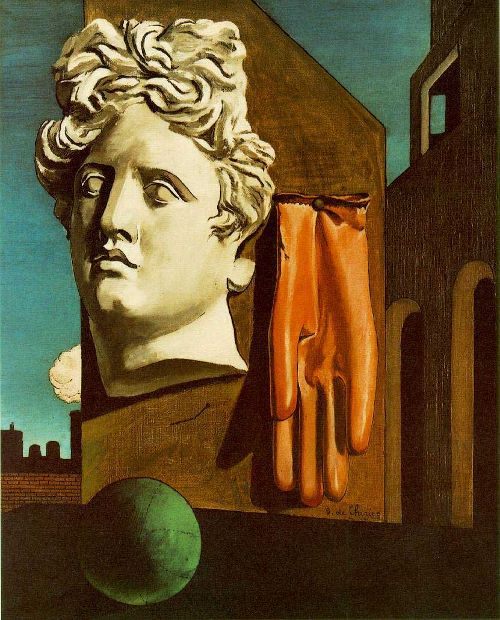

Indeed, Surrealist precursors began influencing artists about a decade before the term was first used. When the Belgian painter, René Magritte, born on this day, 21st November, in 1898, saw the dream-like 1914 work, the Song of Love, by the Greco-Italian artist Giorgio de Chirico, he understood that “it represented a complete break with the mental habits of artists who are prisoners of talent, virtuosity, and all the little aesthetic specialities: it was a new vision.”

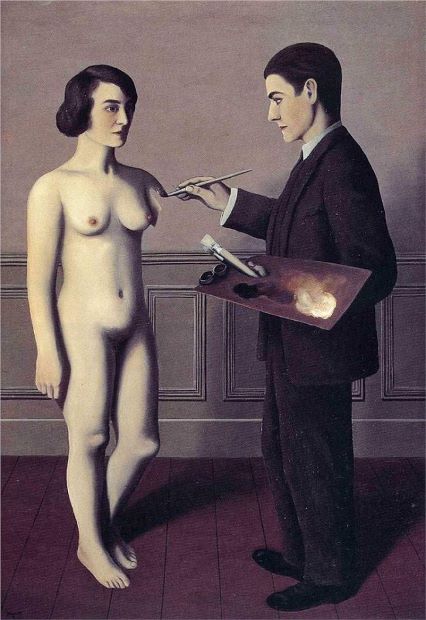

“He followed this lead throughout most of his life,” writes Gombrich, “and many of his dream-like images, painted with mysterious accuracy and exhibited with puzzling tiles, are memorable because they are inexplicable.” The historian takes the example of this 1928 painting, Attempting the Impossible, suggesting its title might serve as a motto for Magritte and his fellow Surrealists.

“Magritte’s artist (and it is a self-portrait) attempts the standard task of the academies, the painting of a nude, but he realizes that what he does is not copying reality but rather creating a new reality, much as we do in our dreams. How we do it we do not know.” Over a century after his birth, the image remains enigmatic; testament, perhaps, to the artist’s great talent for painting so accurately, things patently not there.

For a greater understanding of René Magritte buy this concise overview; for a solid introduction to Surrealism, buy this book; and for greater insight into this era and many others, buy a copy of EH Gombrich's The Story of Art here.